Graham Reid | | 7 min read

Sharma, Kabra, Chaurasia: Rag Piloo

Very few musicians could claim to have not only changed the musical direction and possibilities of their chosen instrument, but of also of having played a key role in how that instrument was constructed and developed.

In South Korea, the master musician Byungki Hwang (interviewed here) rescued the tradition of the gayageum from being lost, and in the West the great guitarist Les Paul not only made exceptional advances in technology (tape delays, multi-tracking etc) but also created a distinctive sound in country, jazz and rock'n'roll.

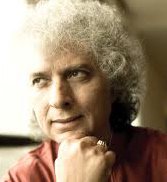

In this rare company we must also include Shivkumar Sharma from India, the master of the santoor and the man who brought the instrument – through his technical modifications and playing style – into the Indian classical tradition.

Prior to Sharma, the multi-stringed santoor was simply a folk instrument played in Kashmir. After him, the instrument has been an accepted part of the Indian classical repertoire of instruments.

At 74, Sharma remains modest about his elevated position and pays immediate credit to his guru, his father.

“My father, Pandit Umar Dutt Sharma – 'pandit' means maestro in Indian and great musicians are addressed like this – was a very versatile musician and vocalist who knew tabla [drums] and various other instruments.

“When I was five years old he started teaching me vocal and tabla and gradually I got more interested in tabla. But when I was about nine or 10 he said I was going to play some unknown instrument. That was decided by my father who was very learned and had this vision to introduce santoor [into the classical world].

“So he worked on the santoor for some time and he decided he should teach me the instrument when I was about 12 or 13. Because I had the background of vocal and tabla, and I picked things up very fast.”

Sharma was in his mid teens when he

gave his first important public concert on santoor at a gathering of

famous Indian musicians in Bombay. He admits the initial reaction to

this instrument was mixed and that laymen were more accepting of this

different kind of instrument.

Sharma was in his mid teens when he

gave his first important public concert on santoor at a gathering of

famous Indian musicians in Bombay. He admits the initial reaction to

this instrument was mixed and that laymen were more accepting of this

different kind of instrument.

“But for musicians, they felt this instrument was incomplete. At that time I was playing the original Kashmiri santoor and had not done any modifications and the instrument had many limitations.

“Afterwards I thought if I had to play this instrument I would have to create a distinct character for it, and a playing technique . . . and the whole style of music.

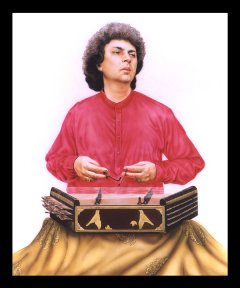

“The first thing I did was to improve the tonal quality. If you listen to the music of santoor now it is totally different to the sound which we had in the 50s. In Kashmir it is still played on a small stand and played by squatting in front of the instrument.

“I started to take it on the lap to cut the extra vibrations. The second thing I did was, because of the way it was tuned with the 100 strings you could not play all the ragas, I changed the tuning and increased the range of the instrument.

“And finally, as you have seen this is a stringed instrument played with wooden mallets, I discovered a technique where, while playing with the mallets, I could reproduce the nuances of the Indian vocal system.”

Although Sharma makes this sound quick and logical, the whole process took over a decade but then “the skeptics who had dismissed this instrument said it was now happening and that I must keep on playing the instrument. They were some of the senior musicians of our country.”

Today the santoor is made in most of the major cities in India, and those in Kolkata, Mumbai and Delhi are making the instrument today in line with the modifications Sharma introduced four decades ago. In Kashmir however, most make the instrument in the traditional manner.

Sharma notes the santoor has musical relatives throughout the world and was mentioned in Vedic scripture where there is reference in Sanskrit to “the 100-string lute”. In the valleys of Kashmir it is used as an accompaniment to Sufi ceremonies.

“There is a theory in India that gypsies traveled from India and went to different parts of the world and they might have taken the instrument with them.”

He ticks off countries which have similar instruments – Germany, Hungary, Romania, the santoor in Iran, santouri in Greece,in China the qinqin, similar instruments in Central Asia and even as far away as America there is the hammered dulcimer.

“They are all similar instruments, the only difference is in Kashmir they have got 100 strings and because it is mentioned in Vedic scripture we can connect them, and that the instrument originated in India.”

At the start of the Sixties, Sharma began what became his life, touring constantly – the day we speak he is just back from playing all over India in the past year – and taking the hypnotic sound of santoor to audiences as far afield as the United States and Europe, the South Pacific and to Japan where he has a number of musical disciples.

The biggest breakthrough he made

however came in '67, right at the height of the hippie era and an

interest in all things Indian by that generation.

The biggest breakthrough he made

however came in '67, right at the height of the hippie era and an

interest in all things Indian by that generation.

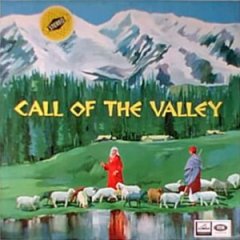

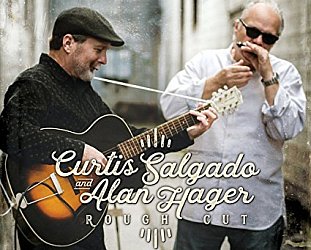

By great coincidence and good fortune, he, slide guitarist Brijbushan Kabra and flute player Hariprasad Chaurasia recorded the concept album Call of the Valley, an impressionistic series of pieces which follow a day in a Kashmiri valley.

The album was internationally hailed for its subtle charm and depth of emotion (it is an Essential Elsewhere album here).

When it was reissued on CD in '95 on EMI's

Hemisphere imprint (right), it was acclaimed all over again.

When it was reissued on CD in '95 on EMI's

Hemisphere imprint (right), it was acclaimed all over again.

“That was the first thematic classical music album in India. And Brijbushan Kabra had introduced Indian slide guitar into classical music.

“When we recorded it we had no idea how people would connect to it, but it made a tremendous impact on old and young, and people who had never heard Indian classical music started listening to other [Indian] instruments and vocal music.

“I used to meet people in those days who told me they were introduced to Indian classical music because of Call of the Valley. And it is, surprisingly, still popular. I meet people who say they still listen to that music,” he laughs.

For a period from '80, he and Chaurasia composed film music for features by the famous Indian director Yash Chopra (the duo were known as “Shiv-Hari”) but he admits he found that a challenge. And is bemused by the current high profile of Indian films in the West.

“Nowadays they call it 'Bollywood' and I don't understand what that means,” he laughs. “We call it Hindi film. But we composed for some of the very, very popular movies of our country and the director Chopra is one of the most respected and great.

“It is very challenging work for a classical musician because we are used to going on stage to play what we choose to play and what we have learned and practiced. But this is a different ballgame and we are given a situation to compose this song.

“We have to keep in mind the characters, location, storyline and the lyrics. And that becomes the background score. If you take out that background score and watch the film you will not be able to enjoy it because the background score puts life into the dialogue and their expressions.

“We had wonderful experiences doing that . . . and they called us musical directors not musical composers.”

He says after about eight scores with Chaurasia they moved back into the world they knew best, classical music, but even now people ask if they are going to do more scores.

“This is a compliment but the reason we don't is that our loyalty, right from the beginning has been to classical music. And now our schedule is such that we are traveling and don't get time to sit back and compose for film.

“But now there is a different genre and style of music is coming into Hindi films, a move from serious poetry and melody to more exciting rhythms and electronic sounds. So that's another reason we don't get inspired.”

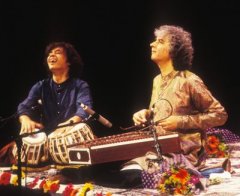

But he is busy enough with constant

touring (right, with tabla player Zakir Hussain) and teaching and he acknowledges he has experienced what

people say, “that music is the universal language which goes beyond

caste and creed and whatever”.

But he is busy enough with constant

touring (right, with tabla player Zakir Hussain) and teaching and he acknowledges he has experienced what

people say, “that music is the universal language which goes beyond

caste and creed and whatever”.

I have personally experienced that. I think sometimes that it was God's grace whatever has happened in my life. Of course there was my guru, my father, but I also think some divine force made me a medium and God has given all this to me. And I am thankful to that divine force.

“Playing on a concert platform and stage is a unique experience. You get an immediate response from an audience and that gives you an inspiration to do something better.

“You know, after finishing a concert people are so polite and they come and tell me how great it was and how they are moved by the music.

“That is nice, but my thoughts are somewhere else. I am thinking, where could I do better. I never get 100 percent satisfaction from any concert, and I pray to the Almighty that I keep this thinking intact in my mind.

“If that thinking is there, that I could not do it full justice, then there is still hope for me, after 60 years of playing, to maybe do something better tomorrow.”

Shivkumar Sharma is one of the artists playing this year's Womad in New Plymouth.

For more on Indian music start your search here, and for an interview with Ravi Shankar go here.

post a comment