Graham Reid | | 11 min read

Carnavalito del Ciempies/Dance of the Centipedes

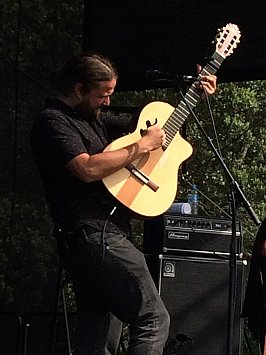

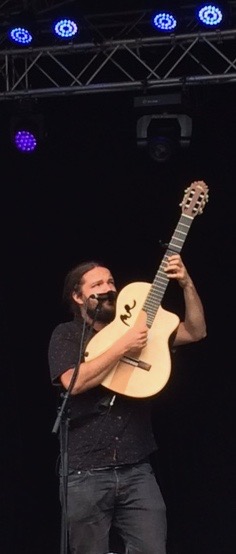

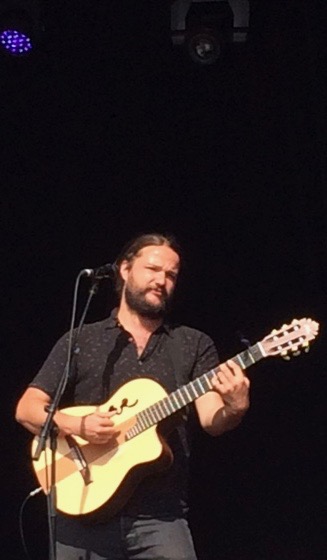

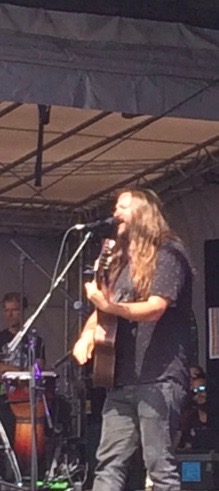

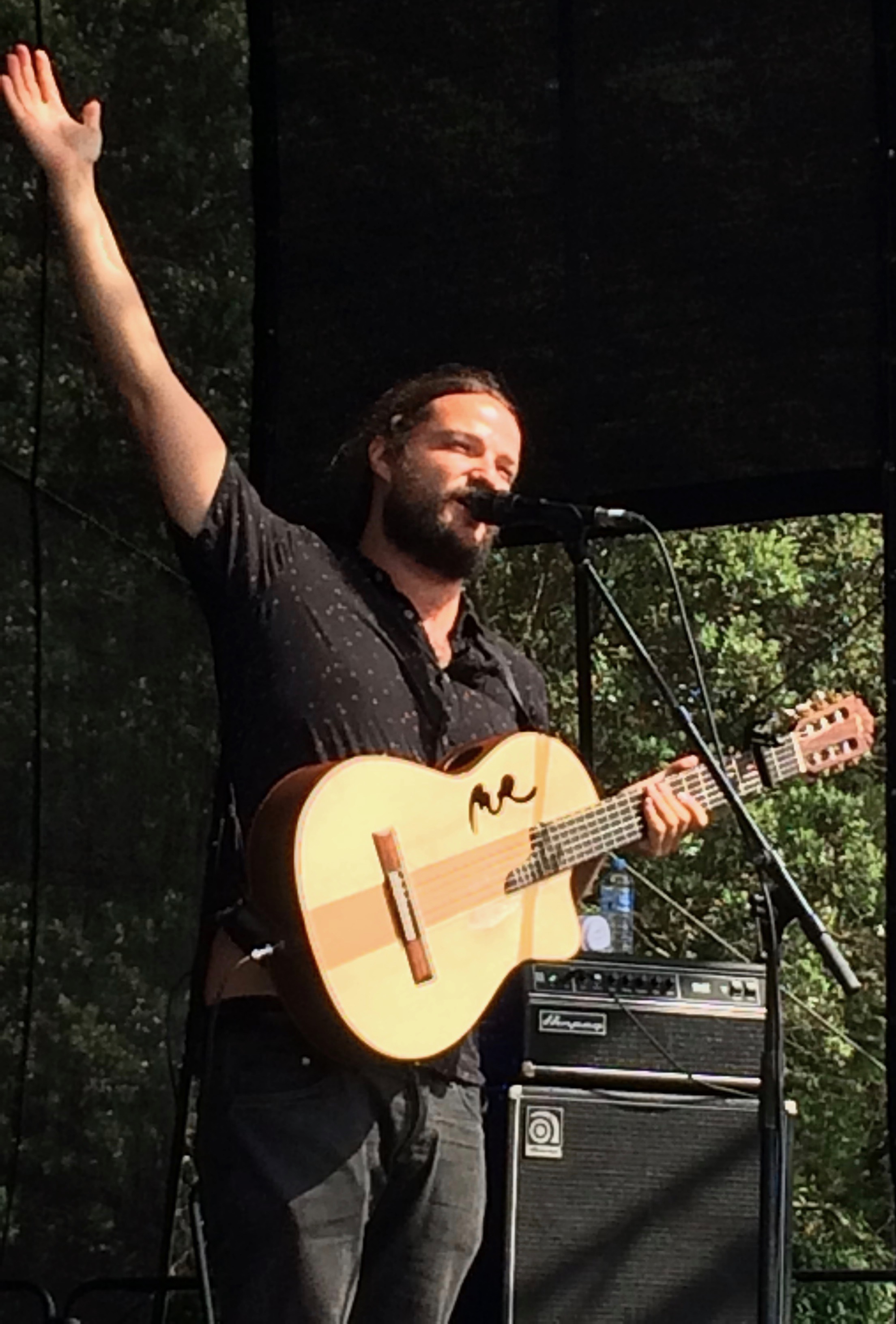

Towards the end of his sometimes incendiary, frequently danceable and always enjoyable afternoon set at Womad, the Chilean singer/guitarist – and mean fiddler – Nano Stern took time out to tell a story to the huge crowd before him.

He spoke of his architect father asking him when he was a teenager what he wanted to do in life, and he replying that he wanted to be a singer. His father was dismissive of this as not being real job (not like being a stage hand or in the sound crew, Stern quipped) but then later in life when his father was very ill they spoke again.

His father said he should do exactly what he wanted to do so that every morning when he looked in the mirror he would be happy.

And that, said Stern -- his waist-length unbraided from previously being tied back and hanging to his waist -- is what he wanted for us.

He hoped that his music would make us

all a bit happier than we were before they started playing so

tomorrow when we looked in the mirror . . .

He hoped that his music would make us

all a bit happier than we were before they started playing so

tomorrow when we looked in the mirror . . .

In that regard, as the massive cheer from the crowd attested, it was mission accomplished.

The personable, funny and yet also serious Stern continued into the closing overs of his set with his small band – neatly dropping in “Don't it always seem to go, you don't know what you got till it's gone” in English – then closed with a foot-stomper.

He was one of the least known but best received acts of the Womad weekend, and that was confirmed when there was a capacity crowd for him doing his Taste the World session where international guests prepare favourite dishes (“Garlic is to cooking as madness is to art” he said quoting the American sculptor Augusts Saint-Gaudens) with celebrity chef Jax Hamilton.

Nano Stern was further proof that music is an international language because, aside from rare moments, all his songs were in Spanish but he somehow sold the passion and wit in the lyrics to a crowd where few would have understood him.

Sitting in the media area the day before he proves to be funny and passionate, personable and honest.

Of course we get a soundcheck at fast

turnaround festivals like this, he says: “1 2 3 and go, as short as

possible to keep the energy” he laughs.

Of course we get a soundcheck at fast

turnaround festivals like this, he says: “1 2 3 and go, as short as

possible to keep the energy” he laughs.

The somewhat surprising thing about this seemingly itinerant, very politicised musician-cum-poet who travels with an acoustic guitar and not much else is that he spent time studying contemporary classical music and composition in a conservatory.

“Yes, I did that for just one year and then I quit, but I learned a great deal. I would have to separate that from me now because it was just one year. But when you are 18 one year is so long and I was just out of school. It was a crash into the world of contemporary music and possibilities that I never would have thought of.

“I got to study Bartok and Stravinsky from my knowledge of music in school but then got further into more freaky stuff like Ligeti and Pierre Boulez, then music that really appealed to me very much like minimalism. Minimalism in a modern context like Arvo Part from Estonia. This music really spoke to me.

“It is only later that I understood

why this music spoke to me. Arvo Part for instance, it appealed

because it has a much stronger association with his culture and roots

and to a spirituality . . . as well as a political stance which was

very clear. He was censored to by the Soviet regime and he had to go

and live in Berlin to go into this spiritual and pure thing he wanted

to do. I find that very inspiring.”

“It is only later that I understood

why this music spoke to me. Arvo Part for instance, it appealed

because it has a much stronger association with his culture and roots

and to a spirituality . . . as well as a political stance which was

very clear. He was censored to by the Soviet regime and he had to go

and live in Berlin to go into this spiritual and pure thing he wanted

to do. I find that very inspiring.”

Coming from Chile with its volatile history n the 20th century – the socialist president Salvadore Allende deposed in '73 by a CIA-backed coup led by General Augusto Pinochet who lead a military-backed dictatorship as president until '88 – meant Stern grew up with politics as a backdrop. His parents grew up in a very different Chile under the oppressive regime.

“Absolutely, and my grandparents grew up in Europe [the family name is Britzmann] and had to leave and were forced into exile and had to escape for their lives. So those of my family then who didn't escape were killed. Politics was a very real thing.”

A dinner table conversation?

“Not really because there were clashing views but it was not taboo. My father was very open that we talked about things, but I am the youngest of four, quite a bit younger than my older sister, and she would very much clash with my parents. As I assume my parents would have clashed with my grandparents.

“I think that taught me to be humble

about things, you are never completely right or completely wrong.”

“I think that taught me to be humble

about things, you are never completely right or completely wrong.”

And of course – being born in '85 – he was very much of the post-punk generation.

“Oh yes, I was like every sensitive 14-year old, I was into music but I was very, very lucky because I went straight into proper professional bands with people 10 and 20 years older than me. Because I could play.

“At three I started to play violin

but also my grandfather was a musician, an accordionist and pianist

and he was a semi-professional musician. Also my sister was a

songwriter, so I had music coming at me from all sides.”

The

Chilean style he plays today derived from folk didn't come until a

little later however.

“It was sort of there but at 14 or 15 it was not something I was aware of but it was happening all around me so you absorb it, no?

“But then I started playing with two rock bands [Matorral and Mecanica Popular] which were quite unique back then because they were the only bands in Chilean scene who were having something to do with folk music with the traditions and putting it into a rock context. It was very strange back then and had not been done since the Seventies really.

“Those two bands in which I was by far the youngest, one became quite famous and the other sort of like one of the dark things that people really follow, like a cult band.

“But then I left them to travel but when I came back to Chile 10 years later my thing it had became an established reality, that folk music had everything to do with rock and electronic music.”

And Chilean folk a vehicle for poetry

and political comment?

And Chilean folk a vehicle for poetry

and political comment?

Absolutely, it has been so at least since the second half of the 20th century and a little in the first half as well. But before that it has more of a rural context where it is more traditional singing about farmer and cows and horses and Chilean topics,” he laughs.

“But within the tradition there are very contingent things and if you listen carefully many of the old songs have deeper meanings which is a very beautiful way to learn how to be sarcastic and be smart about it!”

For the past decade Stern has been one of the most significant Chilean musicians with acclaimed albums and a considerable international reputation, most among Hispanic communities.

“I am very much within my generation of musicians who are now in our early Thirties. And yes, I am . . . I cannot answer this without sounding arrogant . . . but within that I am among the best known. And being here and touring internationally as a young musician from the arse of the world, Chile, it is not so likely.

“We have made seven tours in three years in the US and we are going there in April again to play Chicago, New York, San Francisco and Boston. And then I am going to Mexico.”

There is a big Hispanic community in Boston?

“Oh yes, everywhere [in the US] . . .

except New England! But everywhere else you go there is a big

population, people get surprised when I mention some of these places

but there are five times more native Spanish speakers there than in

the total population of Chile.

“Oh yes, everywhere [in the US] . . .

except New England! But everywhere else you go there is a big

population, people get surprised when I mention some of these places

but there are five times more native Spanish speakers there than in

the total population of Chile.

“But anyway music transcends the language barrier and Womad is perfect evidence of that. All around there is this wonderful music.

“For me I try to go beyond the world music cliché where I dress in some traditional costume and people go, “Oh wonderful” and they dance. I try to deliver a strong and clear message and that I do in English or whatever language I am faced with. I speak a number of languages and when not there is always one language in common that people have . . . although I have never been to the far east of Asia ,but I imagine you can always connect somehow.”

I mention that political comment at Womad is of the most benign or bland cliches like “We are all one” or “one love”. Such crowd-pleasing announcements, even if sincere, come off to often as mere platitudes but Stern – who spoke about the role of women and dedicated a song to their patience, power and suffering, drills down deeper than the blandishments.

“I agree [about the cliches]. It does get a bit trickier here where you are not much in touch with the local contingencies. But for example in Australia at the first Womad [Womadelaide] I said what I wanted to say and then someone approached me and he was a refuge who had been imprisoned on Manus Island and he had been tortured.

“He had been sent to Adelaide for treatment because he had been so badly tortured and he escaped the hospital. So I invited him to go on stage with me the next day to give his testimony which he couldn't do because he was illegal and clandestine.

“But he wrote a letter and I ended up reading this letter to Australians, a letter from a prisoner of their own government who had been tortured by their taxpayer money.

“It was a very full-on moment and I didn't see any other things like in the festival where issues were approached in that way. Sometimes I think, 'Am I going too far?' and 'Is it the role of a Chilean folk musician to come to Australia and do that?'

“But it is a global situation and we

are a global people and we have to approach these things. I always

comment, especially the context of a Womad festival, because it is

very much coming like that 'think globally and act locally' thing

people say.

“But it is a global situation and we

are a global people and we have to approach these things. I always

comment, especially the context of a Womad festival, because it is

very much coming like that 'think globally and act locally' thing

people say.

“I think that too, but it is also now important to think locally and act globally, it is important to keep in mind the dynamics of our communities and to think of the world as one thing.

“We need to act in the world because

the problems that are urgent now can only be addressed by acting

globally.”

Reading a letter from a Manus Island prisoner to a

Womad audience of well disposed liberals is one thing, taking the

message wider is the question though.

“True, but we have toured in the Mid West of America and I do tend to moderate a little bit because for simple reason, it is not cool to shit in people's living room.

“You have to be aware of their reality, that it is not their fault, but it can be a little bit scary for us, a bit creepy.

“You know all these people probably have guns at home and if I speak about immigrants they are probably going to boo me. But of course I do it. You don't preach to the coverts, you must do it to the others . . . and that is much more challenging.

“And much more fun,” he laughs.

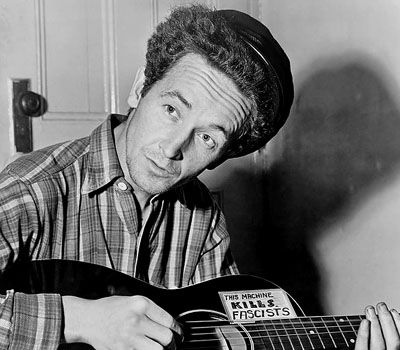

“But dangerous. We have played in

venues which have a sign which says 'Guns not allowed' but other have

the sign 'Guns allowed'. That is okay. I let my guitar be my weapon

in the good tradition of Woody Guthrie.”

“But dangerous. We have played in

venues which have a sign which says 'Guns not allowed' but other have

the sign 'Guns allowed'. That is okay. I let my guitar be my weapon

in the good tradition of Woody Guthrie.”

[Note: Woody Guthrie had written on his guitar "this machine kills fascists"]

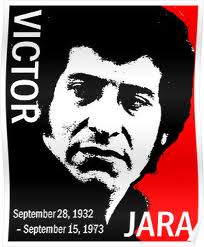

We speak about the politics of Chile and a digression into how in the Irish tradition – among others – singers keep the names of the martyrs, disappeared and murder alive in song. He says there is something similar in Chile but not to the extent as in Ireland. He cites songs by the writer, poet, activist and singer Victor Jara who was murdered by Pinochet regime after the coup of '73.

“So yes, there is that tradition and very much with Jara because he was murdered for political reasons. He was the most well known person, after Allende the president of course, to be murdered, the most well known civilian, non-government person to be murdered.

[Note: the nature of Allende's death is disputed but most say he took his own life.]

“Jara became an icon and his death has not been brought to justice even now and that has kept him alive because we are seeing, all of us, demanding justice. His killer is known and he is living in Florida and not being extradited because the CIA probably made a deal with him. I don't know.

“It is important to remind yourself of these icons and many, many, many times I play Victor Jara songs in our shows. It is a good reminder of how far things can go when you let things go wrong.

“The [Pinochet] coup and dictatorship was a traumatic spot in our history and will remain so for many generations to come. [Jara] alongside Salvador Allende are perhaps the most iconic victims then with a specific Chilean tradition of singing to people about martyrs.”

The week before our conversation a new government took power in Chile lead by President Sebastian Pinera and Stern sees no reason to be cheerful at all.

“We are in the first week of a right wing government by the same guy who was president four years ago and it is kind of depressing to see the same people who were the civilian accomplices of the dictatorship are now running the country.

“Chile is sort of running a dictatorship within a democracy which is the creation of a dictatorship, our constitution is a not a legitimate democratic constitution but it runs underneath that so it is handcuffed completely.

“It is an illusion and [this new

government] runs in the direction of maintaining an extreme and quite

hardcore free-market, neo-liberal society in which citizens are seen

as consumers.”

“It is an illusion and [this new

government] runs in the direction of maintaining an extreme and quite

hardcore free-market, neo-liberal society in which citizens are seen

as consumers.”

And the chances of Chile slipping back into the dark days of the past?

“That couldn't happen again because it is not the Seventies and the world has changed so much. If there would be any such thing as a socialist approach in the 21st century it would have to be very different, with different ways and answers.

“And also a very different aesthetic, because artists and thinkers and musicians who are creating thoughts and new ideas need to know our traditions and respect them, not just our folk traditions but also our political history . . . and also to realise the worst possible position is to be nostalgic about [the Allende socialist era] constantly.

“It has to speak to us in a different way without cutting us off from our history.

“I hope to be able to give back from my position as a musician . . . and also just as a citizen.”

All live photos copyright Megan Stunzner. Used with permission.

For other interviews with artists at Womad 2018 start here. For a review of the festival go here.

.

.

post a comment