Graham Reid | | 7 min read

Malkauns

Among the big and familiar performers at this year's Womad in Taranaki – Angelique Kidjo, Nadia Reid, Teeks, Ria Hall and the Silk Road Ensemble to mention a few – there is someone whose name may not be well known but he's a man who is one of the most revered masters of his art.

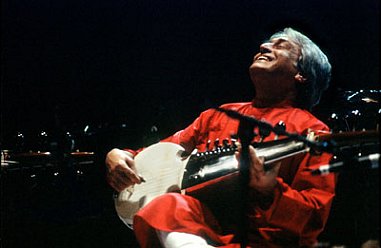

This living legend is Amjad Ali Khan who, at 73, has been acclaimed for more half a century and -- with the death in 2009 of Ali Akbar Khan (no relation) – became the world's most respected Indian classical musician, a man who has extended the repertoire and reach of his instrument the sarod.

The multi-stringed sarod – four or five main steel strings, usually two drone and many other sympathetic strings and a fretless steel neck – has a beautiful singing and sliding sound, and in the past few decades has drawn equal with the more familiar sound of the sitar.

For many years Amjad has toured with his two sons Amaan and Ayaan (also both playing sarod) whom he taught, just as his father Hafiz taught him and his grandfather had taught Hafiz.

It is sometimes said that the family invented the sarod back in the mists of centuries ago.

But although grounded in tradition, Amjad Ali Khan has extended the repertoire and sound of the instrument, written new ragas and – as the late Ravi Shankar did for the vocabulary and reach of the sitar – has worked with Western musicians across the spectrum, from classical orchestra and choirs to pop performers.

But although grounded in tradition, Amjad Ali Khan has extended the repertoire and sound of the instrument, written new ragas and – as the late Ravi Shankar did for the vocabulary and reach of the sitar – has worked with Western musicians across the spectrum, from classical orchestra and choirs to pop performers.

There is even an album of Christmas songs he recorded on sarod, and the electro-beat remix of Joy to the World is something to hear.

He was won numerous accolades in India, has been made an honorary citizen of Houston, Nashville and Tulsa, is a UNICEF ambassador and . . .

Much, much more.

It is early morning in New Delhi when he cheerfully answers the phone and announces this is the the best time in India, the season is pleasant and in the morning – it is 9.30am when we speak – it is still cool. (A check reveals it to already be 23 degrees.)

And what does the day hold? Some practice perhaps?

“I don't practice every day, but mentally most of the time I am thinking about music and in my memory I am singing, humming or composing. But within the gap of one or two days I sit also with my instrument because the constant touch with your instrument means that even now you do discover something new and different or better, something I could not do earlier.”

“I don't practice every day, but mentally most of the time I am thinking about music and in my memory I am singing, humming or composing. But within the gap of one or two days I sit also with my instrument because the constant touch with your instrument means that even now you do discover something new and different or better, something I could not do earlier.”

He says he is constantly exploring new possibilities on the instrument. He has made modifications to the traditional model, something purists objected to, but sees that as part of extending the sound and repertoire.

“The sound of the sarod has been changing by maestros of different calibres and I have been trying to make my presentation more accessible, interesting and appealing. Presentation is the most important aspect of any musician.

“Generally Indian classical musicians take a long time to warm up and a long time to end their concerts. I feel that a sense of presentation most important, a 10 minute piece of music is also a complete raga. To show the raga it is not necessary to continue it to one or two hours.

“If you have a feeling of the composition of a raga it will tell you the complete raga.

“The composition was created historically to preserve the raga. When the time came where musicians were given a lot of time to improvise the raga that became a convention.

“Convention is a very unhealthy word, I don't like it.”

This – along with the unity of all people under one god – is a repeated refrain in his conversation. He is exact about his language.

“Most of the musicians talk of 'tradition', but they are confused. They are actually meaning 'convention' and they cling to convention. It is like religion. Today people blindly follow a religion, nobody ever questions. I can't imagine what it is like to be radical.

“In my family my wife is Hindu and I am Muslim, but we believe that we have a common god, because we come to and go from the world the same way.

“So all of us have a common god like we have common musical notes, like the seven 'fa-so-la . . . ' and then with flat and sharp we have 12 notes. All over the world whatever the musician we are all connected to these notes.

“The music has connected the world, but language is various.”

As with many musicians from the Middle East and the Indian subcontinent, Amjad learned music through the family lineage and the oral tradition of passing on ragas, stories and techniques. He started learning as a child and gave his first recital at age six. Since then he has considered his audiences paramount and has tried always to communicate with them, bridging the gap between the elite classical tradition and more popular music. He has played folk and pop tunes alongside the great ragas of India.

As with many musicians from the Middle East and the Indian subcontinent, Amjad learned music through the family lineage and the oral tradition of passing on ragas, stories and techniques. He started learning as a child and gave his first recital at age six. Since then he has considered his audiences paramount and has tried always to communicate with them, bridging the gap between the elite classical tradition and more popular music. He has played folk and pop tunes alongside the great ragas of India.

“Historically in Indian classical music there was the oral tradition. I did not learn music through books, I didn't have to time to read any books actually. So I believe in the present and whatever I think is right I do with my life. I don't blindly follow convention whether it be classical music or religion. I respect all religions, all the faiths, because I believe we are a common race.

“My father was a very old-timer and belonged to the old world culture but was very compassionate and kind, and he was called 'the Prophet of Sarod' because he gave a different language to the sarod in his lifetime.

“I had many siblings and uncles but I was the youngest child and so he was concentrating on me a lot. I always wanted to sing through my sarod, I don't play sarod but I sing through my sarod,” he says then sings a plaintive series of notes and microtones.

“That is the true sound that I cannot manipulate. The politician can manipulate language but in music our live is very transparent. If I am out of tune it will come to be known,” he laughs.

“Gradually from age of 12 the people of India from every corner cultivated and nurtured me, there are so many problems with Hindu and Muslim. But I was born into a family of musicians and my forefathers were given so much respect and honour all across India and the people encouraged me to be what I am today.

“My presentation is totally different from other sarod players.”

This has not always been unanimously well received so, I make a mistake here, his music and approach was controversial with “those people who were more traditional”?

He laughs, “Again, you are using the wrong expression. The traditional people allow innovation but the people who blindly follow convention they may not agree with my presentation. They would criticise and as a human being I often think about this: Why do the priests of every religion not tell people that we have a common god, but the priests have their own agenda and they are not interested in uniting the world.

He laughs, “Again, you are using the wrong expression. The traditional people allow innovation but the people who blindly follow convention they may not agree with my presentation. They would criticise and as a human being I often think about this: Why do the priests of every religion not tell people that we have a common god, but the priests have their own agenda and they are not interested in uniting the world.

“I believe in the power and energy that brings us to the world and take us from the world.”

Not all of his music is improvised and he is pleased to note his composition Samaagam of 2011 as being one of a number of scored pieces which was originally played by the Scottish Chamber Orchestra and has since been played by a number of international orchestra, a number of them in the US.

From folk tunes to Christmas carols, extended classical pieces to short ragas, from concert halls in Japan, Europe and the US to outdoor appearances at Womad . . . The work goes on, the tradition passed on to his sons and students.

Quite a remarkable man, the greatest living sarod player of our time.

Some years ago he said, “the real Amjad Ali Khan is the one on stage”. What did he mean by that?

“On the stage I might impress people but off the stage I can do right or wrong or whatever, just be my life. But on the stage what I present is my music.”

His life has not been without private controversy and it is well reported that as a young man he engaged in a long affair with a divorced woman who had a child, she being many years his senior. He wanted to marry her but she rejected his advances although their affair lasted eight years. An arranged marriage didn't work out either.

His life has not been without private controversy and it is well reported that as a young man he engaged in a long affair with a divorced woman who had a child, she being many years his senior. He wanted to marry her but she rejected his advances although their affair lasted eight years. An arranged marriage didn't work out either.

Then he met the dancer Subhalakshmi Barooah, a Hindu woman, and they married . . . crossing that religious divide which has been so problematic in India.

He says that these aspects of his life opened his mind and that is why there is the real Amjad on stage, because the flawed man is not there but the musician is.

“I feel that somebody else is guiding me then, somewhere in the cosmic powers there is a conductor who is guiding me and I am just transmitting.

“The messages are coming and I am passing them to my audience.”

WOMAD New Zealand 2019 will see the festival celebrate its 15th anniversary in the stunning 55-acre Brooklands Park and the TSB Bowl of Brooklands, New Plymouth, 15-17 March 2019.

For further information and ticketing see the official Womad site here.

Mike Pearson - Jan 31, 2019

Good interview and great track.

Savepost a comment