Graham Reid | | 2 min read

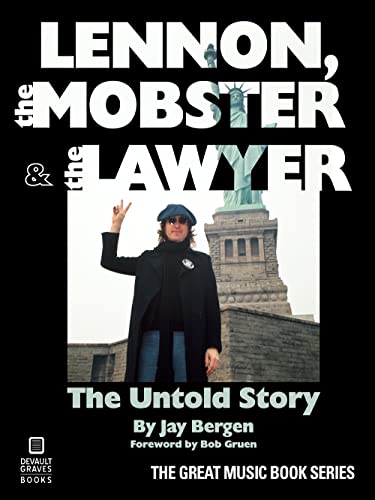

Although the author seems to possess that uncanny and unlikely ability to recall and quote lengthy conversations many decades after the events, this is still a fascinating account of the courtroom showdown between John Lennon and the old-school, Mob-connected record company grifter Morris Levy who ripped off artists, put his name on songs to get publishing credit and used the threat of expensive litigation to browbeat musicians.

Levy was a nasty piece of work, but until the early Seventies he'd never encountered a musician like Lennon.

Not that Lennon had any case to answer, but the former Beatle had seen the likes of Levy before (Allen Klein who briefly managed him was cut from similarly litigious cloth) and Lennon had something few other musicians enjoyed: time.

When the case came to court in 1975-76 Lennon was in his house-husband phase, not short of money and had ample time to prepare his case, meet with his lawyer Bergen who has written this book (mostly from reliable court transcripts) and could appear before the judge to give evidence.

When the case came to court in 1975-76 Lennon was in his house-husband phase, not short of money and had ample time to prepare his case, meet with his lawyer Bergen who has written this book (mostly from reliable court transcripts) and could appear before the judge to give evidence.

Levy – some say the model for Hesh Rabkin in The Sopranos – had been used to cornering much more minor players in music through his Roulette Records and other interests.

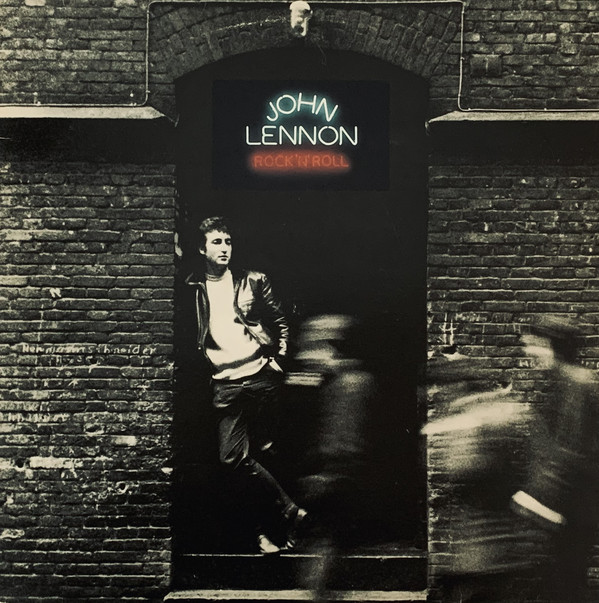

The reason Levy and Lennon ended up in court was because Lennon was recording material for what would become his Rock'n'Roll album (to come out through EMI/Capitol) and at Levy's insistence had sent Levy some rough tapes because he was obligated to record songs from catalogues Levy owned. That was because he'd used a line from a Chuck Berry song You Can't Catch Me in the Beatles' Come Together, and Levy had an interest in the Berry catalogue.

Although even that was in doubt as Bergen notes: the Berry line is “here come a flattop” (which means a convertible car) and Lennon sang “here come old flat top” (which Bergen notes refers to a man with a crewcut).

No matter.

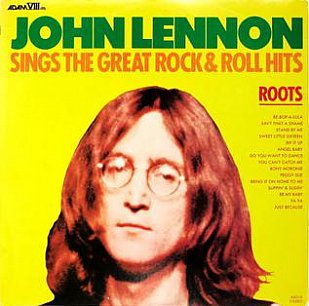

The rough tapes Lennon sent Levy – the relationship complicated by Lennon having been at Levy's farm with some musicians and going to Disneyland in Florida with him and family – were enough for the grifter to quickly release them as Roots in an embarrassingly shoddy cover and sell the album through TV advertising.

Levy insisted Lennon had given him the okay.

Levy insisted Lennon had given him the okay.

When EMI/Capitol heard of this they rush-released Lennon's far superior and properly mixed Rock'n'Roll. But of course the marketplace was confused, Lennon's artistic integrity was damaged by the cheap Levy album and EMI/Capitol argued because they couldn't prepare proper ads and video clips the sales of Rock'n'Roll suffered.

Bergen – who admits to being excited by the prospect of representing a former Beatle but also having lost touch with rock music – walks the reader through the machinery of the court cases and Lennon comes off clear and articulate when he presents himself before a judge who knew nothing of pop culture but was genuinely curious about the process of recording and marketing.

It makes for fascinating reading (Levy never really stood much of a chance), especially when Lennon explains just why he wanted to make an album of rock'n'roll oldies, and what those particular songs meant to him.

It goes without saying Levy lost heavily and Lennon -- with the supportive but mostly distant Ono -- returned to the quiet life. But not before Lennon had to explain his avant-garde work, the Two Virgins cover and what recording meant to him before an astute judge who asked insightful questions . . . and ended up a fan of Peggy Sue.

Maybe that song title appealed to him?

post a comment