Graham Reid | | 4 min read

Gimme Shelter

Award-winning Wellington author, broadcaster, critic and the incoming Lilburn Research Fellowship scholar for 2023 Nick Bollinger has written an excellent book about a seemingly inchoate area in our recent history.

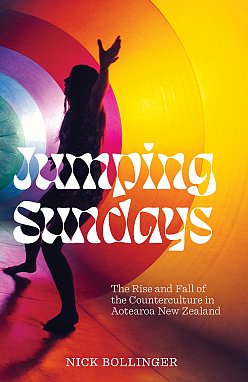

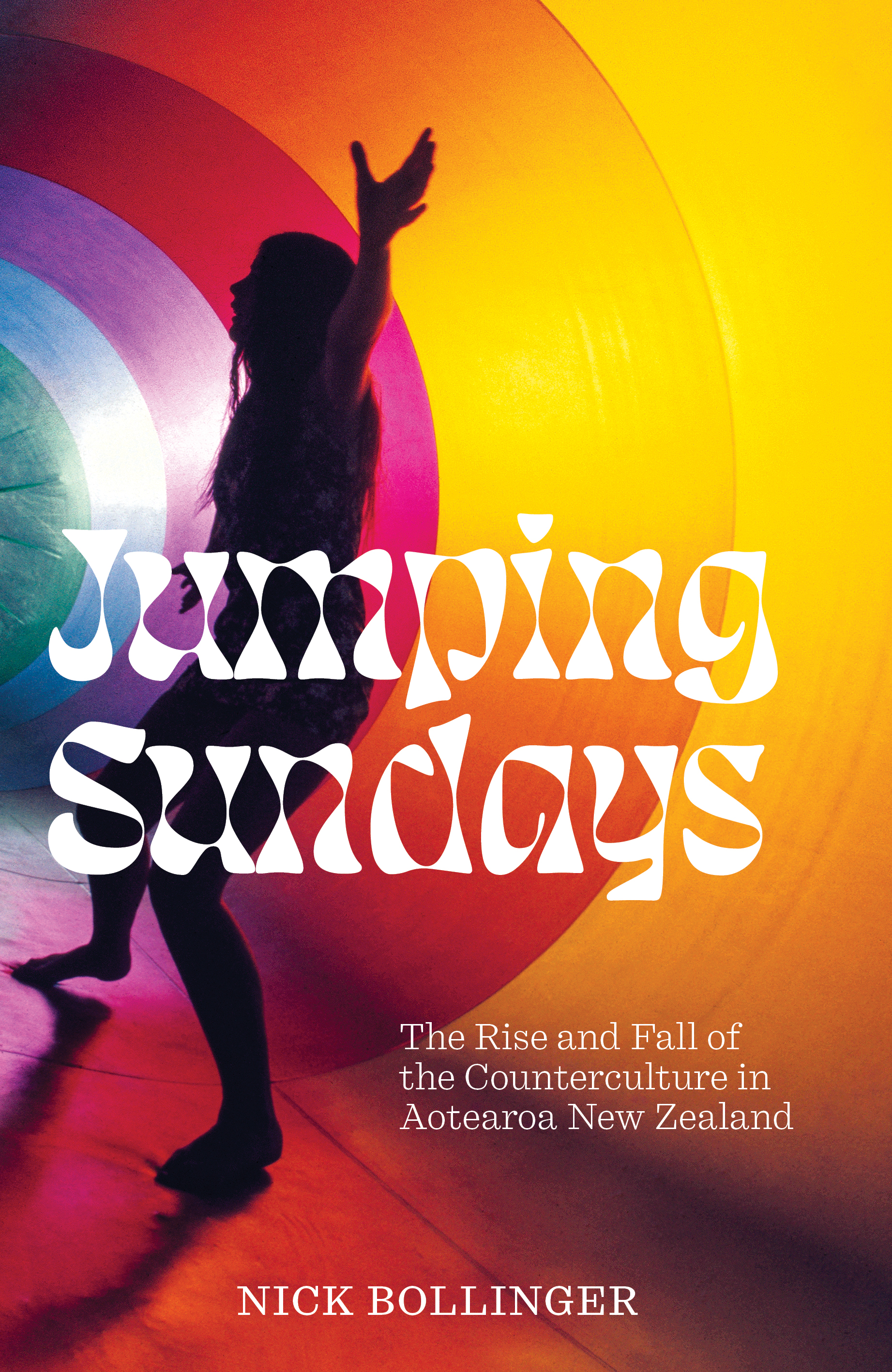

It is Jumping Sundays: The Rise and the Fall of the Counterculture in Aotearoa New Zealand.

It has been reviewed by Graham Reid at Kete Books here, but we are pleased to be able to offer an extract with permission from the publishers.

.

SCENES FROM THE REVOLUTION

While live music was an important part of the emerging culture, records remained the primary carriers of musical information, as crucial in their own way as films or literature.

To the English writer David Hepworth, the long-playing album was ‘a semi-precious object, a mark of sophistication, a measure of wealth, an instrument of education, a unit of currency, a banner to be carried before one through the streets, a poster saying things one dare not say oneself, a means of attracting the opposite sex, and, for hundreds of thousands of young people, the single most cherished inanimate object in their lives’. 1

If the LP held such significance to Hepworth growing up in West Yorkshire, to a young inhabitant of a colonial island nation in the South Pacific it meant all that and more. LPs brought messages from the other side of the world.

They were a precious connection to a global movement of ideas, sounds and meanings. Many of the tantalising titles one read about in the sea-freighted music magazines were not available locally and so became the stuff of myth.

To have actually heard Trout Mask Replica, The Gilded Palace of Sin or the self-titled third album of the Velvet Underground was to have gained admittance to an exclusive sect.

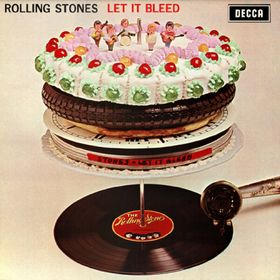

Of the albums that saw local releases, a few acquired a totemic importance, and none more so than the Rolling Stones’ Let It Bleed. Released at the tail end of 1969, it would be the counterculture’s ubiquitous soundtrack until the Stones superseded themselves with Sticky Fingers eighteen months later.

It was the perennial party record, an accompaniment to endless varieties of free-expressive dance, yet it doubled as a dispatch from the frontlines. Bookended with scenes from the revolution — ‘Gimme Shelter’ (‘war, children, it’s just a shot away’) and ‘You Can’t Always Get What You Want’ (‘I went down to the demonstration, to get my fair share of abuse’) — the album burst like a volley of Molotov cocktails aimed at bourgeois morality.

Its title song makes fun of the Beatles’ pious ‘Let It Be’ with allusions to menstruation and oral sex.2In ‘Monkey Man’ it’s all junkies, satanic messiahs and ‘lemon-squeezers’ (a sexual euphemism borrowed from the bluesman Robert Johnson), while ‘Live With Me’ lampoons the peccadilloes of the English upper class.

Its title song makes fun of the Beatles’ pious ‘Let It Be’ with allusions to menstruation and oral sex.2In ‘Monkey Man’ it’s all junkies, satanic messiahs and ‘lemon-squeezers’ (a sexual euphemism borrowed from the bluesman Robert Johnson), while ‘Live With Me’ lampoons the peccadilloes of the English upper class.

But there is also the sexual violence of ‘Midnight Rambler’, a blues boogie with gothic overtones, in which Jagger plays the role of a psychopathic rapist. If the effect could be called psychodrama, it also amplifies the casual misogyny of many a countercultural male.

As the sixties rolled towards the seventies, Let It Bleed seemed a long way from the songs of idealised, innocent love that had filled the air less than a decade earlier — a measure of how much the world had changed. The week of its release, California had hosted an event that history would record as the anti-Woodstock: a hastily arranged oneday festival at the Altamont Speedway that had disintegrated into an orgy of violence and bad vibes.

The Stones were the headliners.

A few weeks after the Great Ngaruawahia Music Festival, the Stones returned to New Zealand for the first time since the mid-sixties. By this time the countercultural landscape of the northern hemisphere they had observed so acutely in Let It Bleed had, in many ways, been replicated down under.

There had been violent demonstrations and a fair share of abuse; lots of sex, some of it falling conspicuously outside the societal conventions of marriage, monogamy, heterosexuality and the missionary position. And there were drugs — marijuana, psychedelics and now, increasingly, heroin.

Rachel Stace was at Western Springs to see them, nearly nine years after she had screamed for the Beatles as a schoolgirl in Wellington. Those days seemed so innocent now.

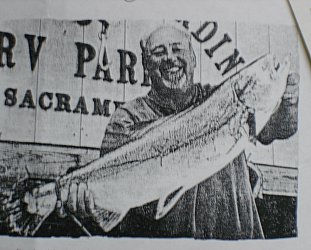

Her life since had become more dangerous, thanks to a recreational diet of marijuana and acid supplemented with Mandrax and opiates. A photograph taken at the concert shows her and a group of her closest friends standing among the mostly seated, summer-afternoon crowd.

Her life since had become more dangerous, thanks to a recreational diet of marijuana and acid supplemented with Mandrax and opiates. A photograph taken at the concert shows her and a group of her closest friends standing among the mostly seated, summer-afternoon crowd.

Rachel, in round wire-rimmed glasses, stands near the centre of the group, holding a cigarette and sporting a peacock feather. To her left is Grant: tall, longhaired, in mirror shades, beads and pink crushed-velvet jacket slashed to reveal a bare chest — a rock star in search of a band.

To her right is Jane in flowing headscarf, bracelets and rings.

Beside Jane is Sally.

‘He was a real queen,’ Rachel remembers. ‘Apparently he was called Sally because he was brought up by the Salvation Army, but his real name was David.’3

The group looks glamorous and decadent, as though they really belong on the stage.

The photo appeared in Craccum alongside a review of the concert, and has since been reproduced in newspapers to illustrate nostalgia stories about the hippie era. But to Rachel the image is bittersweet.

Both Jane and Grant would die prematurely after struggles with addiction.

Sally, to Rachel’s surprise, is still alive.

.

1 Hepworth, A Fabulous Creation, p. 3.

2 Though the Beatles had already recorded ‘Let It Be’ in early 1969, and the Stones evidently knew about it, the song would not be released until March 1970, the Stones pre-empting them by three months, possibly lessening the impact of the joke.

3 Rachel Stace, author interview, 13 March 2019.

.

Jumping Sundays: The Rise and Fall of the Counterculture in Aotearoa New Zealand by Nick Bollinger, Auckland University Press, $49.99

.

post a comment