Graham Reid | | 4 min read

The British inmates of Colditz – the fortress castle in the heart of Germany where the Nazis kept the most valuable prisoners and recidivist POW escapees – were mustachioed, stiff-upper-lip officers who planned their escape back to Blighty to have another crack at Jerry.

Here the spirit of heroic Britain was kept alive and, although there was humour to be had in mocking their captors, the serious business of meticulously plotted escapes was the main preoccupation.

At least that has been the public perception, honed by the likes of former inmate Pat Reid who wrote The Colditz Story in 1952 which became a best-seller and was followed quickly by two more boyishly enthusiastic books about life on the inside of this huge and gloomy fortress.

These provided the basis for the enormously popular – and very good – BBC television series Colditz in the early Seventies.

Reid – no relation – created the myth of Colditz where inmates like the flying ace Douglas Bader were incarcerated.

Bader's story – losing both legs in a flying accident in 1931, cajoling his way into the RAF during the war, capture and escape – was burnished by the biography Reach for the Sky by Paul Brickhill and the film adaptation starring the enormously popular and archetypal British actor Kenneth More.

Bader's story – losing both legs in a flying accident in 1931, cajoling his way into the RAF during the war, capture and escape – was burnished by the biography Reach for the Sky by Paul Brickhill and the film adaptation starring the enormously popular and archetypal British actor Kenneth More.

But it was all bosh and bullshit as this remarkable book by the assiduous researcher and crisp writer Ben Macintyre (who also wrote Operation Mincemeat, recently adapted for the screen) shows in page after compelling page.

Inside Colditz the British class system was endemic (officers permitted to escape, their orderlies were not), there was racism, mutual masturbation, greed and treachery.

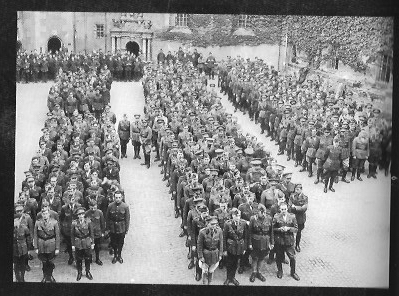

The prison was divided along lines of nationality (British, Dutch, Poles, French) and until some accord between the groups was established each planned their own escapes independently. It was chaotic.

There was suspicion of the various French detainees which included spies and informers loyal to the Nazi puppet government.

In the first year or so escapes were random and not well-planned, and the so-called escape-proof castle was far from that: it was riddled with hidden passageways, tunnels and drainage systems which could be tapped for escape routes. The problem was what to do when you were outside the walls, near a village which celebrated Nazism and Hitler, and some distance from neutral Switzerland and Spain.

There were certainly heroes in Colditz, but they weren't who you might expect.

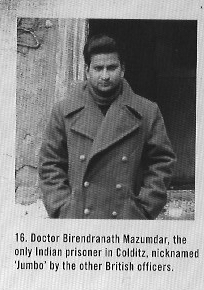

The sole Indian prisoner was the extraordinary Birendranath Mazumdar who came from a wealthy Brahmin family, was educated at elite schools in India, became a doctor, and was accepted into the Royal College of Surgeons in London when he moved there. He spoke six languages (French and German among them, English with an aristocratic accent), was considered proud, fastidious, funny and ambitious.

He was also conflicted because he supported the nationalist aspirations of the Indian independence movement, supported Mahatma Gandhi and was a follower of the radical nationalist Subhas Chandra Bose.

He was also conflicted because he supported the nationalist aspirations of the Indian independence movement, supported Mahatma Gandhi and was a follower of the radical nationalist Subhas Chandra Bose.

And that meant the British in Colditz viewed him with considerable suspicion and ostracized him. They called him Jumbo.

The Germans thought he could be an important asset.

But Mazumdar pledged loyalty to Britain when the war broke out, had a brief but heroic career in France before being captured and inside Colditz flatly refused to cooperate with the Germans, even when they took him to Berlin to meet with Bose in the expectation the two of them would begin a counter-insurgency against the British in South East Asia.

Just by being taken to Berlin fed even greater suspicion by the British in Colditz and yet Mazumdar remained steadfast. His marginalisation continued after the war and he was investigated by MI5.

He was one of the most heroic figures inside Colditz, as was the overweight, Jewish dentist from Scotland Julius Green whose courage took a very different and quietly active form.

Others too in these pages exhibited some of the qualities of the cliched image of the inmates, but here too is the foppish and foolish British national Walter Purdy who was a Nazi sympathizer and collaborator, wrote propaganda for the Gestapo, broadcast from Germany to Britain in the manner of the infamous Lord Haw Haw, and after the war was tried for high treason and hanged.

He was a pathetic figure, prone to lying and never quite understood the depths of his treachery.

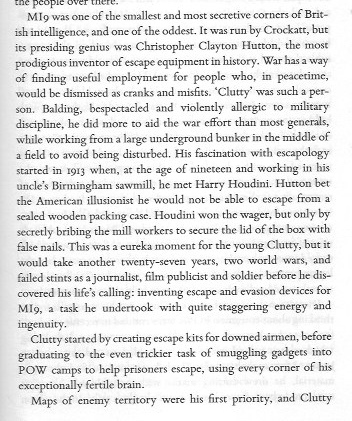

These and dozens of other fascinating characters – anti-Nazi women outside the wall among them, and the remarkable eccentric in Britain mentioned below – populate this extraordinary story of men desperate to escape Colditz but in the closing months of the war found it more reassuring – slightly reassuring – to stay inside and away from the grip on the SS who were keen to take over control of the prison. And indeed did march many inmates out to their death.

Oh and Douglas Bader?

You can read about him for yourself. What a shit of a man.

.

COLDITZ, PRISONERS OF THE CASTLE by BEN MACINTYRE. Viking/Penguin $40

.

Gillian Wrightson - Jan 14, 2023

Thanks Graham

SaveLooking forward to watching this

Cheers

G

post a comment