Graham Reid | | 6 min read

The internet has robbed us of many things, mostly an intelligent dialogue and the ability to disagree without resorting to personal insults.

But it also has opened the small corners of the world to us, so ideas, people, cultures, places and music we might not have known existed are now readily available.

However there is a downside to that also, particularly in the world of popular music and how it is discovered and disseminated.

It is generally considered that grunge was the last great musical movement before the age of the internet. Those bands emerged from a scene in and around Seattle/Portland. Away from the hubs of New York, Los Angeles and Nashville the scene grew and fed itself, just as Liverpool in England, Kingston in Jamaica and Memphis in Tennessee had done in the decades before.

The idea of a scene has been crucial to the development of popular music and musicians.

Now however if two decent bands emerge of out some small town in the American Midwest, remote Australia, the jungles of Thailand or a small city in southernmost New Zealand you can bet the internet will “discover” them and they will be given a global platform, even if they're still in the development phase.

Scenes in music emerge of themselves, are often inward looking but self-supporting with a network of fellow travelers, sympathetic bar owners, artists and maybe even an independent record company.

Fanzines would spring up, the passion of those true believers.

When the first flickerings of what would become Flying Nun and the “Dunedin sound” emerged there was no internet and the scene could develop at its own pace, musicians sharing rehearsal space, members, sometimes lovers and an embrace of fans and followers built around the music and musicians.

Without that -- or with the sudden and early attention from the rapacious social media of today -- it's likely bands like the Chills, Clean, Verlaines and others would have had very short life-spans.

Without that -- or with the sudden and early attention from the rapacious social media of today -- it's likely bands like the Chills, Clean, Verlaines and others would have had very short life-spans.

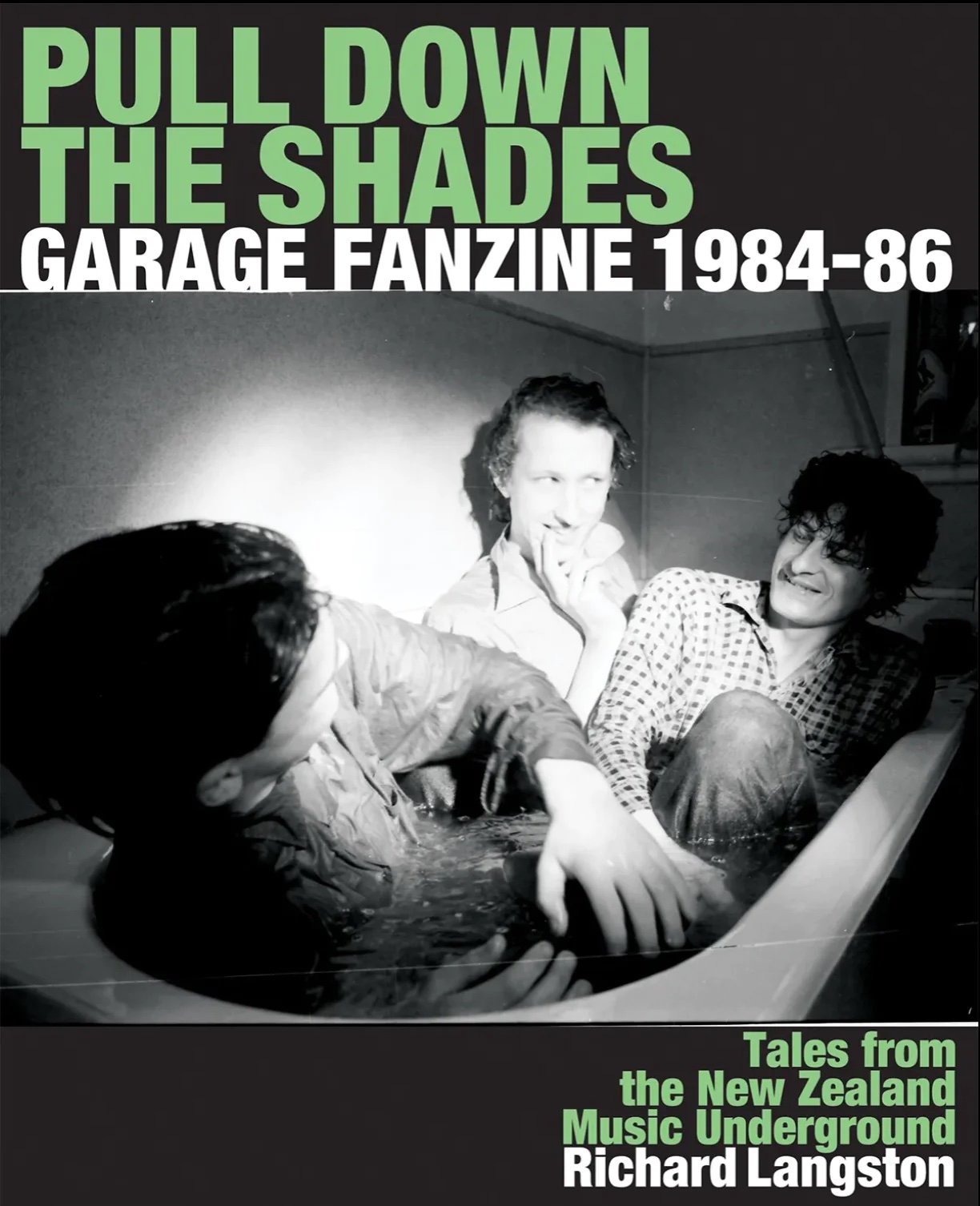

But they survived and sometimes thrived, and had their champions like the fanzine Garage edited/created by Richard Langston, the first issue of which was just 50 copies of cheaply collated and photocopied pages celebrating the Verlaines, Chills, Tall Dwarfs and others in roughly typed copy with handmade artwork, collages and black'n'white photos.

It might have looked amateurish but it was, and proudly so.

It was also popular

The small profit from it was recycled into printing 200 more copies.

“Among the musicians there was a sense of community and competition,” says Langston in Pull Down the Shades, a compendium of Garage issues.

“Among the musicians there was a sense of community and competition,” says Langston in Pull Down the Shades, a compendium of Garage issues.

“As songwriters, they were constantly out to top each other.

"At the time we punters were unaware of the competition to write the best new song — we just made sure we were at the pub to hear the end results.

"In time I did get to know the musicians — it was hard not to given my interests and the small-town nature of Dunedin.”

Then came the even better Garage #2 and by Garage #3 the fanzine – which was featuring interviews and live reviews – was given a grant.

They bought an electric typewriter.

By then some of the bands were also on an upward trajectory, recordings had been made, mainstream media attention was looking south to Christchurch and Dunedin.

By then some of the bands were also on an upward trajectory, recordings had been made, mainstream media attention was looking south to Christchurch and Dunedin.

Garage#4 looked and felt more professional but the fanzine attitude and enthusiasm remained intact.

They were exciting times and for $1.50 Garage captured them and spread the word. The interviews were wonderfully unmediated and unfiltered, the scope widened to include the new wave of emerging bands out of Auckland.

International artists (Jesus and Mary Chain, Cramps) were interviewed, outsider overseas artists (Roky Erikson) were profiled,

Garage – despite its humble origins – remains a touchstone for anyone wanting to know “what was it like back then?”.

Much sought after by collectors, Garage now gets collated into the insightful 282-page book Pull Down the Shades: Garage Fanzine 1984-86 by editor/creator Langston.

Subtitled as Tales from the New Zealand Music Underground, it collects not just the original pages in all their ragged glory (well presented however) but brings together eloquent, more contemporary, comment from many of the protagonists of the time.

Subtitled as Tales from the New Zealand Music Underground, it collects not just the original pages in all their ragged glory (well presented however) but brings together eloquent, more contemporary, comment from many of the protagonists of the time.

Beyond the reproduction of the Garage pages there are contemporary interviews with, among others, Alec Bathgate (Enemy, Toy Love, Tall Dwarfs), Shayne Carter (Bored Games, Doublehappys, Straitjacket Fits, Dimmer), Bill Direen (too many incarnations to list), George Henderson (ditto), Francesca Griffin (Look Blue Go Purple, FG and the Bus Shelter Boys), artist Ronnie Van Hout (Into the Void) and many others.

All bring astute insight and reflection.

In the closing pages there are excellent tributes to the late Hamish Kilgour from friends and fellow musicians here and in New York.

However looking back on those early days and Garage, David Kilgour (Clean, Great Unwashed etc) says, “You must have an opinion! Even I can remember in the early 80s storming out of a party as the people had unacceptable music tastes and could not understand the greatness of The Who’s Sell Out. Goodbye little people.

However looking back on those early days and Garage, David Kilgour (Clean, Great Unwashed etc) says, “You must have an opinion! Even I can remember in the early 80s storming out of a party as the people had unacceptable music tastes and could not understand the greatness of The Who’s Sell Out. Goodbye little people.

“Youth and life can give you this pith and vinegar, and so it should. Yeah music is oxygen and it needs to be pure, my kind of pure, ha!

“From the get-go Garage had an identifiable look. I always loved the hard contrast black and white look of the covers and the almost slapstick look overall. Richard's friends and helpers seemed to be all well- read literature hounds, academics even, teachers, lager louts, musicians, and yes, Richard is and was a journalist. Which helps when you're a rabid music freak trying to write with passion and smarts.

“It's no surprise the writing throughout all the issues is right on the button, but always unashamedly caring. Sure this was Richard's project, but from

the outside it seemed a group effort.”

Bruce Russell (Xpressway, Dead C etc) notes, “Given that at the time the mainstream music media was pivoting rapidly to cover the ‘new music’ — what was the point of a fanzine? Their point of difference was that fanzines presented the self-understanding of the artists and their audience — unmediated by what ‘journalists’ or other gatekeepers thought was important to cover, or acceptable to say.

Bruce Russell (Xpressway, Dead C etc) notes, “Given that at the time the mainstream music media was pivoting rapidly to cover the ‘new music’ — what was the point of a fanzine? Their point of difference was that fanzines presented the self-understanding of the artists and their audience — unmediated by what ‘journalists’ or other gatekeepers thought was important to cover, or acceptable to say.

“And furthermore, by their very nature, fanzines were a way of defining the field of practice: who was ‘us,’ and who was ‘them.’ ”

These days – as we noted at the start – our interconnected world is very much divided into factions, most of them just shouting across the emptiness in capital letters.

Garage was more subtle than that, it came from a world where conversation and debate were encouraged and opinions not just expected but welcomed.

Yes, that insular world had its sniping, factions, petty jealousies and divisions. But Garage captured the enthusiasm and excitement of being young and creative, and being ready to take it – whatever “it” was – as far as it could go.

Yes, that insular world had its sniping, factions, petty jealousies and divisions. But Garage captured the enthusiasm and excitement of being young and creative, and being ready to take it – whatever “it” was – as far as it could go.

Pull Down the Shades – 282 illustrated pages well laid out, limited edition of 500 copies at present – in an important addition to the growing catalogue of books about that world at the bottom of the known world.

Fanzines still exist but not in the same way as Garage which was as integral to the development of the scene around it as many of the bands it covered.

.

PULLDOWN THE SHADES, GARAGE FANZINE 1984-86, edited by RICHARD LANGSTON. $59. Available now on order from Flying Nun here.

.

post a comment