Graham Reid | | 6 min read

Hard Work, from Victory

For a band which enjoyed a hit single, recorded just one album then fell apart almost 50 years ago, many myths, much misinformation and numerous questions surround Auckland's Space Waltz.

Not the least, were they even a band?

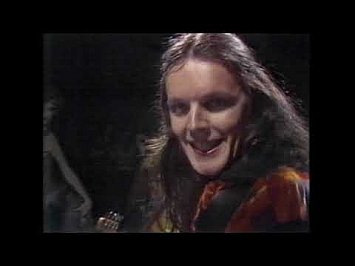

They were introduced as such on September 1 1974 when they appeared on the New Faces television talent show performing Out on the Street, an outrageously confident appearance where singer Alastair Riddell – mascara, lipstick, salacious grin, camp strut – shocked many in the conservative audience at home.

And, legend has it, judges Nick Karavias, Howard Morrison, Paddy O'Donnell and Phil Warren who didn't get them at all.

And, legend has it, judges Nick Karavias, Howard Morrison, Paddy O'Donnell and Phil Warren who didn't get them at all.

Yet the evidence – gathered by Otago University academic and glam-rock aficionado Ian Chapman in a small, detailed book on the band in the Bloomsbury 33⅓ Oceania imprint – shows general if cautious approval by the judges, Warren saying “great impact, potential, originality . . . I think they've got a great future”.

In the final some weeks later – with a brief clip of Out on the Street playing every episode, thus ensuring the song's high profile -- they performed the difficult Beautiful Boy to lesser success, coming sixth.

But by then Out on the Street was a hit.

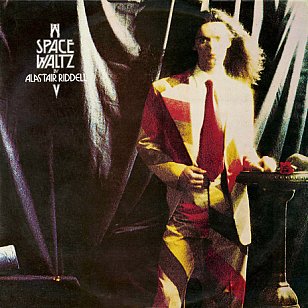

However the subsequent album was presented as Space Waltz by Alastair Riddell with Riddell on the front cover.

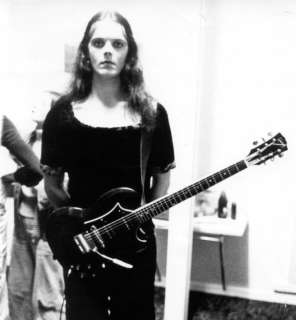

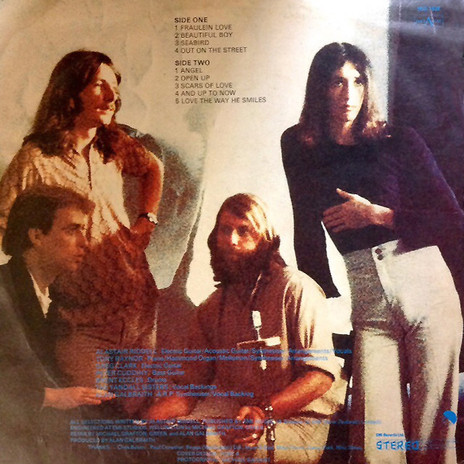

The band – guitarist Greg Clark, bassist Peter Cuddihy, drummer Brent Eccles and keyboard player Tony Raynor (later Eddie, his surname Rayner misspelled) – were relegated to the back.

The band – guitarist Greg Clark, bassist Peter Cuddihy, drummer Brent Eccles and keyboard player Tony Raynor (later Eddie, his surname Rayner misspelled) – were relegated to the back.

Eccles was shocked by the attribution but “just got on with it”; Cuddihy “didn't want to get caught up in any angst”; Clark had no problem and Rayner – Chapman throughout using the incorrect “Raynor” – taken aback, but by then he was in Split Enz anyway.

Riddell said the musicians were there to get his songs recorded.

Chapman analyses what brought them together, the recordings, offers potted biographies of all the main players (producer Alan Galbraith and engineer Michael Grafton-Green included), analyses the cover – designed as a gatefold so all were intended to appear together – and in some detail (with the lyrics helpfully reprinted), the nine songs.

He also notes the album -- and Split Enz' Mental Notes -- only had a pressing run of 500 copies, and that seems remarkably small given the profile it had.

As a fanboy (“I cannot feign impartiality”) he's largely uncritical of an album which divided commentators but was another turning point (alongside Mental Notes, and Ragnarok's debut released almost simultaneously) where local rock uncoupled from mainstream pop.

As a fanboy (“I cannot feign impartiality”) he's largely uncritical of an album which divided commentators but was another turning point (alongside Mental Notes, and Ragnarok's debut released almost simultaneously) where local rock uncoupled from mainstream pop.

He concedes the critical divide and prints producer Galbraith's rejoinder to a negative article in Hot Licks which had taken the album so seriously it ran two separate considerations and a lengthy interview with Riddell.

Under the pseudonym “Blanx” wrote: “[Alastair] has the [Bowie] thesis off pat . . . but he rarely introduces an antithesis (another influence or even some of his own musical personality where'er it lurk) . . . so you're left with Influence Without Direction.”

However fellow critic Brian Thurogood – after forensic track-by-track analysis – concluded, “this album warrants a close listen by all . . . who like to keep up with significant, outstanding music. And if you really get off on good music, without all the intellectual crap, this will suit you too.”

For the 2002 CD reissue of the album this writer said, “Space Waltz fronted by Alistair Riddell was one of the best astral-flight rock bands we had”.

“Mostly unseduced by psychedelic wig-outs but with an ear on Bowie's camp but brittle Ziggy-pop, Riddell wrote tight and edgy guitar rock -- Fraulein Love, Beautiful Boy and the number-one single Out on the Street are local classics.

“Mostly unseduced by psychedelic wig-outs but with an ear on Bowie's camp but brittle Ziggy-pop, Riddell wrote tight and edgy guitar rock -- Fraulein Love, Beautiful Boy and the number-one single Out on the Street are local classics.

“He also penned literate and ambitious prog-rock (Seabird still sounds like he's gargling a thesaurus, however)”.

That last comment stuck with Riddell when he spoke with Chapman about the eight minute-plus Seabird, which dated from his previous band Orb.

“It's about the fact that we repeat mistakes from the past without learning the lessons from them, and then we take them into the future.

“So it's steeped in the overall ideas of the album.

“That said, I did change the lyrics. The chorus was kind've the same, but not the verses.

“I maybe filled-up the lines a bit too much, Graham Reid said it sounded like I'd swallowed a thesaurus.”

“I maybe filled-up the lines a bit too much, Graham Reid said it sounded like I'd swallowed a thesaurus.”

Bowie-Roxy influences sometimes unfairly dogged the debut (the still enjoyable Angel and proto-New Wave Scars of Love) but they were certainly there.

Yet a new audience coming to the reissued album and with this book in hand would probably be less worried about the referencing (and maybe less familiar with the Seventies milieu) than those there in the New Faces era.

Yet even then . . .

Chapman emphasises a yawning cultural divide (the hip new generation Vs conservative rugby-loving masses in the suburbs and small towns) through a dollop of hyperbole, and the idea that history begins with the first thing you remember.

While not wishing to diminish the experience of those in their teens enthralled by Space Waltz on television (Simon Grigg, Gary Steel, Graeme Downes and Chapman himself all speak to that) it's worth noting that others – myself included, I was 23 at the time – had been very familiar with long-haired and sometimes outrageous musicians for many years.

The quirky Split Enz had been on New Faces the previous year and a roll-call would go back to the Underdogs, through Blerta and to record collections which included T Rex's Electric Warrior, plenty of Bowie and Roxy Music.

Yes, New Zealand was fairly conservative at the time – pockets of it stubbornly remain so – but as Nick Bollinger's recent Jumping Sundays showed, there were major currents of difference at work and it wasn't all the pop generation Vs short back'n'sides rugby playing.

While it helps to emphasise just how different from the mainstream entertainment Space Waltz were, the divide was not quite so clear-cut and wide, even in Middle New Zealand.

And to say that Howard Morrison was homophobic because he fluttered his eyelashes to the audience at home isn't fair.

That's a loaded and specific term and Morrison – who'd been in show business (as it was for him) since the late Fifties – had worked with and been around any number of homosexual and sometimes camp men.

His gesture was little more than a nod'n'wink to home viewers that Riddell was probably one of the gay boys, something the performer was amping (and camping) up anyway. You could no more accuse Morrison of homophobia than Riddell of appropriating gay culture. It was all just entertainment.

That said, Chapman's book is a useful and thorough primer and, as the first in the series of the 33⅓ Oceania/Bloomsbury Academic imprint, a very decent start.

Next off the blocks is Matthew Bannister's analysis of Songs From the Front Lawn.

We'd hope thereafter Bloomsbury might cast the net wider than white-boy guitar bands and look to albums by the likes of Anika Moa, David Dallas, Mareko, Bic Runga . . .

Meantime though, Space Waltz is a book worth reading with a copy of the original album at hand.

Meantime though, Space Waltz is a book worth reading with a copy of the original album at hand.

In John Ford's 1962 film The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance a character says, “when legend becomes fact, print the legend”. Legends sell better.

Ian Chapman sells both.

Oh, and with the new Space Waltz album Victory by the original members – which drops four of the original songs (notably Seabird and the equally long Love the Way He Smiles), includes uncannily faithful re-recordings of five (Out On the Street and Fräulein Love among them) and adds new songs by the original band with additional guitarist Solomon Cole – Space Waltz is undeniably a band.

.

Space Waltz by Ian Chapman (33⅓ Oceania/Bloomsbury Academic)

post a comment