Graham Reid | | 5 min read

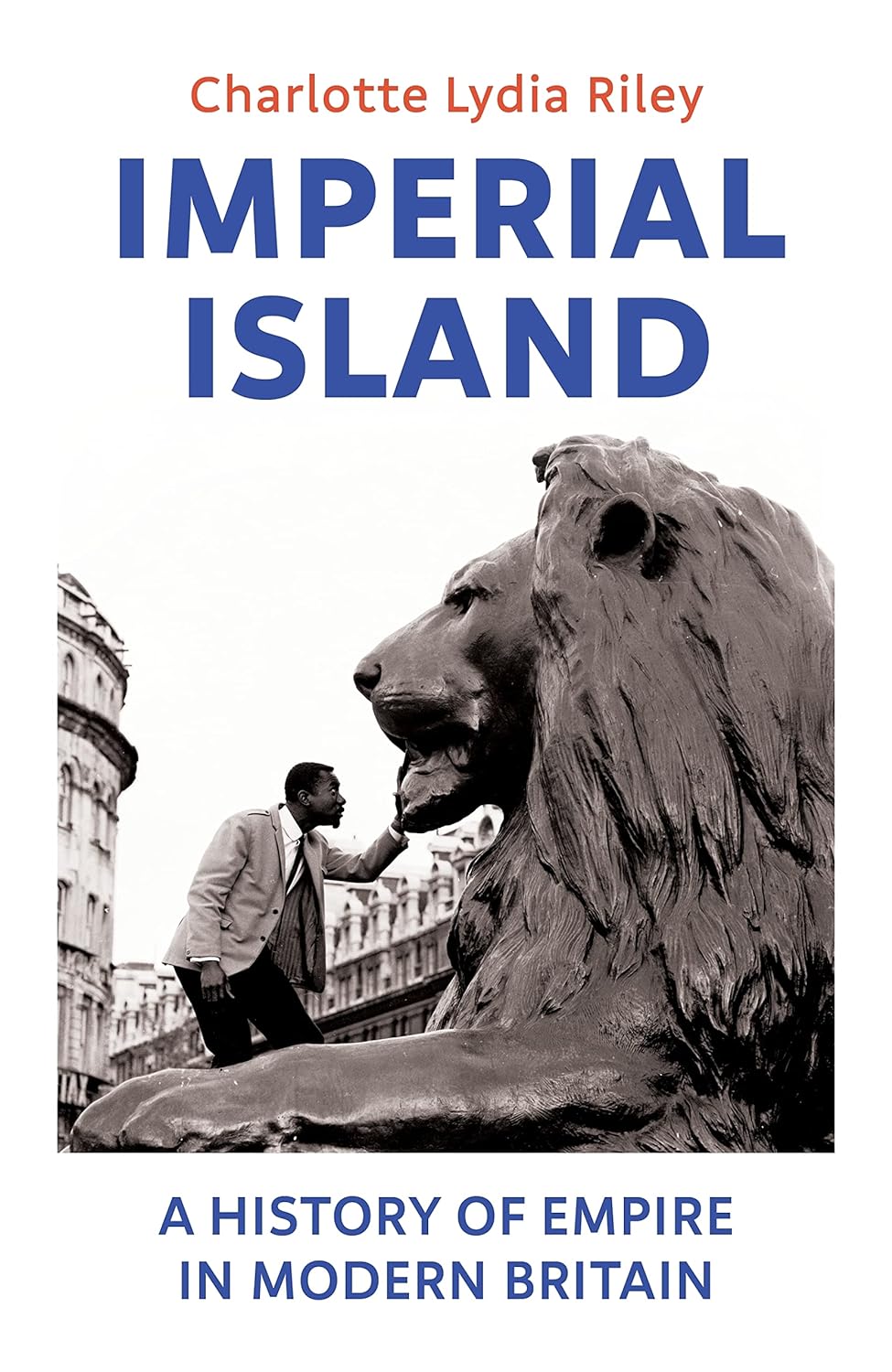

With colonisation under the microscope as a lightning rod in our own country (and sometimes a default position to close down a more wide and deep debate), this interesting if sometimes flawed book allows us to lift our eyes to look through the telescope at how Britain, and most particularly England, has been impacted by its imperial expansion, immigration and then the end of empire through independence movements.

Subtitled A History of Empire in Modern Britain, it is a history of modern Britain from World War I to the present day which peels back layers of imperial arrogance, paternalism and maternalism towards the colonies (especially those of the Indian subcontinent and Africa) and looks at how migrant communities have been marginalised, assimilated and/or affected Britain's view of itself.

Again however, this is mostly a story of England rather than Wales, Scotland and Northern Ireland, and it is also therefore one of class and political alignments.

The much-published author and newspaper commentator Charlotte Lydia Riley is an associate professor and historian specialising in 20th century Britain at the University of Southampton.

And here she shuffles the big movements of history with pertinent quotes from people of all classes and status to illuminate the sometimes dichotomous opinions and experiences of those most affected by migration, changing politics and culture, the tides of economics and often falling prey to their own disadvantage point.

And here she shuffles the big movements of history with pertinent quotes from people of all classes and status to illuminate the sometimes dichotomous opinions and experiences of those most affected by migration, changing politics and culture, the tides of economics and often falling prey to their own disadvantage point.

It makes for a lively if often horrifying read where dry, inherently racist legislation is given a human face or shown to have appalling and enduring consequences.

Myths are dismissed, for example heroic little Britain standing alone during the two world wars when in fact it drew and depended upon hundreds of millions of citizens and the vast produce from its colonies or former colonies for survival.

But sometimes imperialism abroad is conflated into what the author sees as the natural consequence, racism at home.

There is the undeniable racism of some government legislation and ordinary folk: some trade unions come out very badly throughout, defending their (white) workers' jobs from the influx of equally qualified migrants from the Caribbean, India and Africa while accepting (white) migrants from Australia, Canada and New Zealand.

Riley offers persuasive evidence of imperial citizens' contribution to the war effort from 1939–1945 who took up arms, flew aircraft and manned ships, worked in construction and kept the wheels of industry moving. Their fate after the war – and to some extent during it – was most often marginalisation, overt racism, discrimination when it came to employment and housing and . . .

Yet within Britain there were also many who were uncomfortable with the mindset of white superiority and Riley identifies many movements (and individual voices from white, black, Indian and other communities) which actively asserted the rights of migrants, many of whom had arrived from countries where they had been under the yoke of oppression and violent repression by British authorities.

These voices don't shout as loudly as National Front thugs or far right politicians, but they are heard frequently throughout these 380 pages, as are those of white Britons who rejected the cliches and oppressive actions of colonisation.

All the key events of these often tumultuous decades are accounted for, from the 1919 massacre at Amritsar when British troops under the command of General Robert Dyer fired on and killed 379 unarmed men, women and children (Dyer was disciplined, resigned and received a large sum of money raised by the newspaper the Morning Post) through the imperialist disaster of the Suez Crisis, Empire Windrush (and other vessels) bringing migrants from the Caribbean and on to the poisonous rhetoric from Enoch Powell to Nigel Farage (far from the worst and most offensive politicians), the political tub-thumping jingoism of the Falklands conflict, Rock Against Racism, the uber-nationalism of Brexit and so on.

The well-intentioned Live Aid in 1985 is seen through the political lens of further feeding the idea of helpless Africans and the (colonialist) white saviour. A 2012 Oxfam survey showed more than half of British people “immediately mentioned hunger, famine and poverty when asked to speak about Africa while over 40 percent said that they thought conditions in the continent could never improve”.

There are more immediate horror stories everywhere: the British use of interment camps during the Boer War and in Malaysia throughout the Fifties (where they also used Agent Orange defoliant a decade before the Americans in Vietnam); the crushing of the Mau Mau rebellion in Kenya; the 1958 massacre at Batang Kali when 28 unarmed Malay villagers were murdered by the Scots Guard (covered-up until 1970); the scandalous gynaecological examination of women coming from India to meet their fiancés (to see if they were virgins, 1979, believe it or not) . . .

And so it goes, a catalogue of empire beyond the pomp of royal visits, Last Night of the Proms and so on which reaches from old fashioned jingoism to the nationalistic subtexts of Cool Britannia and Britpop.

But if this counter-history to that in textbooks, on television shows like Downton Abbey (the comedies Mind Your Language, It Ain't 'Alf Hot Ma and the like are more easily dismissed for their casual racism) and conversations at gentlemen's clubs in Knightsbridge it comes up short in other areas.

It presumes inward-looking, myopic and insular nationalism (as is happening in this country in many areas) is linked to colonial imperialism and racism.

It presumes inward-looking, myopic and insular nationalism (as is happening in this country in many areas) is linked to colonial imperialism and racism.

Imperialism – beyond its manifestly obvious economic, racist and political consequences – has embedded in it an outward-looking ethos that morphed into ideas of multiculturalism which, when nurtured, benefits all.

Riley is far from excoriatingly negative about Britain in this analysis: for every obnoxious racist group or xenophobic individual there are those who stand up to such things and confront it where it lives, be it in local body elections, the Houses of Parliament or the streets of Brixton and Handsworth.

The book is bracketed by the story of Sri Lankan-born Kamal Chunchie (in 1886, when the island was Ceylon) who emigrated to London at the end of World War I and worked on the docks in what is now the borough of Newman.

Within less than two decades the area had the largest black population in London and Chunchie was active in the church and local political life. He was vice-president of the League of Coloured Peoples in the late Thirties, an auxiliary fire-fighter in World War II, an excellent cricketer, invited to the 1948 Olympics and the Queen's coronation in 1953 and was a man whose life was “shaped profoundly by empire, not the least by its cultures of migration and racism”.

Chunchie disappears from Riley's story after his death in late 1953 but makes an unexpected re-appearance in the final pages.

In July 2021 to mark the occasion of the centenary of the completion of the Royal Docks – and five years after the election of Sadiq Khan as London's mayor, the first Muslim mayor of a major Western capitol city – there was a move to rename the street where London's new City Hall now stands. Among the rejected names were People's Way and World's Gate Way.

It was renamed Kamal Chunchie Way.

There is a lesson in that.

However there are also other lessons for us to be learned here: as the Conservative Party gradually assimilated the ideas of the far right in order to broaden its political appeal, so too Britain's Labour Party followed. This was the pragmatic pursuit of power and little to do with any worthwhile social agenda.

With the right-leaning triumvirate in this country we are already seeing a roll-back of progressive, forward-looking attitudes and legislation. We have been warned in these pages.

Britain also manages to congratulate itself on its anti-slavery laws without probing further into its own role in the trade, witness the outcry from some conservatives about the recent toppling of the statue of slave trader and merchant Edward Colson in Bristol.

If New Zealand rarely appears in Riley's account it hardly matters because there is a bigger picture about self-image we can learn from.

In this country too we have aspects of our history and contemporary beliefs which go unexamined: cliches of clean, green, friendly, unique landscapes (Really? The Southern Alps as seen in the movies?) and tolerance.

These have become part of an unquestioning self-belief in our own unique exceptionalism.

Perhaps that's what happens when you don't look at yourself through the telescope of distance.

.

IMPERIAL ISLAND by CHARLOTTE LYDIA RILEY Bodley Head $40

post a comment