Graham Reid | | 3 min read

Those lucky enough to go to university in the Sixties or Seventies can reflect on halcyon days when a bursary or scholarship made life easier, there were plenty of casual jobs available in holidays and you could have a relaxed attitude all year until a few weeks out from the final exams.

The economic slide, changes in the education system in schools and on-going internal assessment at uni changed all that.

Students today do it very tough.

But back then, as I well recall, we could skip lectures to go the pub, the movies or on a demonstration, of which there were very many. Or, as my friends and I discovered, an even cheaper form of entertainment was sitting at the back of the Magistrates Court and watching the passing parade of ne'er-do-wells and sad cases who would appear there, some with monotonous regularity.

But mostly we went to lectures – although I never understood a damn thing in chemistry – and crammed for final exams at the last minute.

We were enjoying being young before the responsibilities of adulthood arrived. But when we read of what Evelyn Waugh and his crowd got up to in Britain in the years after WW1, we were rank amateurs who couldn't hold our liquor.

In some instances nor could they, but then they were imbibing a whole lot more of it, sometimes starting the day with cocktails before hours of champagne, wine and more cocktails at a long lunch before going out at night for a boozy dinner.

Many in Waugh's circle barely attended a lecture but were almost all highly educated – many fluent in Latin and Greek as well as the Romantic Languages – and by the time they arrived at Oxford from their public schools had read great swathes of important books and contemporary writers.

And they knew how to party.

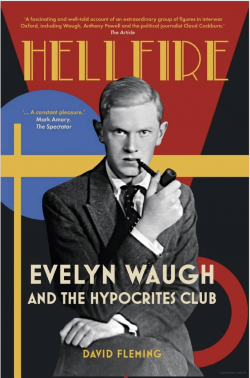

This fascinating book lifts the lid on the lives of those who were young, smart, superior, snooty, sometimes infantile and often relying on parents or family bequests to pay for their clothes, booze, travels through Europe and the Levant, and for the grouse, woodcock and other treats on the dining table.

They lived on credit and threw lavish parties which were notorious for their excess, and for a short while The Hypocrites Club – which a few of them established in 1921 – was where they found themselves, and their lovers.

Many of the characters also found their way into the pages of the novels they wrote, notably Waugh's Brideshead Revisited and his Sword of Honour trilogy.

This was a world of poetry, homosexuality, family connections and – after the short-lived Hypocrites Club was closed in 1924 – the era of the Bright Young Things, jazz, socialism, emergent fascism in Europe and . . .

At some point many of them were forced to find gainful employment which most did despite some of them – Waugh included – leaving university with bare passes. There was only one thing to do now that a comfortable career in politics or The City was off the table: to write.

Fiction appealed to many but some simply resorted to looking down the social scale to journalism, at which many -- like Anthony Powell and Tom Driberg -- were highly successful and influential.

But for every Waugh (troubled, alcohol-fuelled, the conversion to Catholicism), there were people like Brian Howard whose father disapproved of his homosexuality so he persuaded his mother to leave her husband. Thereafter the mother and son pairing became crushingly co-dependent.

He sponged off her, got into debt, she paid out the creditors and he struggled to be even a mediocre writer despite some early promise.

He had everything – wit, talent, dandyism – except he couldn't be disciplined enough to write. But he found plenty of time to drink and take drugs.

A biography of Howard was title Portrait of a Failure.

These pages are crammed with lives as unsuccessful, but many others remarkable for their daring. Among them the great travel writer Robert Byron whose Road to Oxiana has been praised by Jan Morris, Jonathan Raban, Bruce Chatwin and others.

He too was eccentric in his faith: "Byron hadn't forgiven the Vatican for the Great Schism with Eastern Orthodoxy of 1054."

But aside from them and a few other Hypocrites, most of these bright young things of promise and vitality are now forgotten or mere footnotes in the greater story. Which explains why Waugh, their most successful and enduring member, should be on the cover and in the subtitle.

It is interesting just how quickly many renounced homosexuality for marriage and children when they entered the world beyond university. "Ours was womanless Oxford," wrote Peter Quennell in 1976.

Famous names walk through these pages by association: Edith Sitwell, the Mitfords, Jean Cocteau, Charles De Gaulle, Harold McMillan, Guy Burgess . . .

And all the way we know where this is headed, as some of these former Hypocrites encounter the Spanish Civil War and the rise of Hitler and Mussolini. Not all were on the right side of history but many volunteered for military service despite their manifest inadequacies.

The wild stories and the extraordinary lives here begin in chapters with heading like Riotous Assembly, Sweet City, The Eton Society of Arts, Oxford Aesthetes, The Pursuit of Love . . .

The final ones however – in the book and in many lives – come with equally telling titles: The Phoney War, Into Action, Sword of Honour . . .

It is those last chapters where you might think, "God, my generation was very lucky".

.

HELLFIRE: EVELYN WAUGH AND THE HYPOCRITES CLUB by DAVID FLEMING History Press

.

post a comment