Graham Reid | | 6 min read

If you weren't there at the time and looked at just what some today say New Zealand music was in the Eighties, you'd probably conclude it was only Flying Nun, some reggae, mainstream pop and a few noisy underground guitar bands.

But there was a lot more than that reductive view allows.

There was a significant experimental scene, in Auckland most visible with the people around Ivan Zagni and on the Unsung label: groups like Big Sideways, Avant Garage and 3 Voices.

Garage Sale by Avant Garage

Alongside that were albums by Don McGlashan, Besser and Prosser, the rise of From Scratch and a lot of people like the Heptocrats making something along the jazz axis. There was a lot of strange music on cassettes.

Love Song by Ivan Zagni and Don McGlashan

Much of this goes unacknowledged these days.

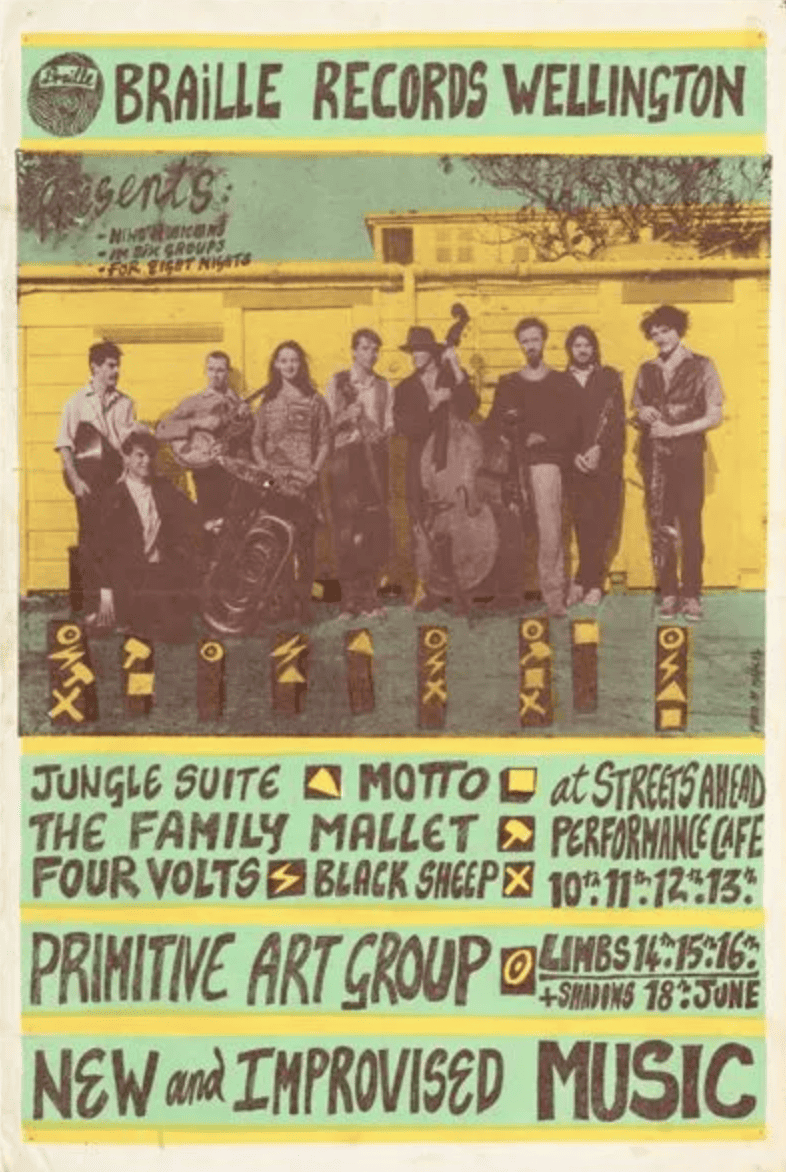

And in the capital was an extremely busy group in the Braille Collective.

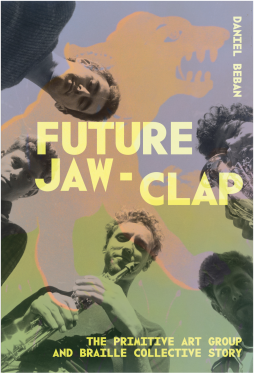

This excellent and detailed book by Wellington sound artist and instrument maker Daniel Beban (who plays in Orchestra of the Spheres and others, manager of the Pyramid Club) is subtitled “The Primitive Art Group And Braille Collective Story”.

He turns his keen eye, evocative words and astute attention to the music and lives of that group of performers out of which came Six Volts, Four Volts and numerous loose configurations.

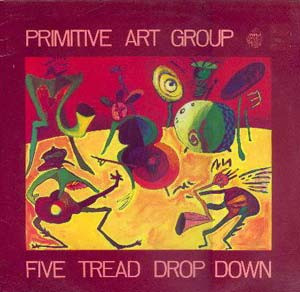

The Primitive Art Group (PAG) were just five musicians but through different configurations and with others on the periphery of PAG, the same small cabal recorded eight albums in two years on their own Braille label.

From Auckland's perspective – especially if you were a long-serving jazz musician – the collective was viewed with some suspicion: the performers were inspired amateurs and the more cynical musicians noted these people's proximity to the Queen Elizabeth Arts Council in Wellington and its funding stream meant they picked up money to release albums when other, undeniably better musicians further afield, just weren't in the running.

From Auckland's perspective – especially if you were a long-serving jazz musician – the collective was viewed with some suspicion: the performers were inspired amateurs and the more cynical musicians noted these people's proximity to the Queen Elizabeth Arts Council in Wellington and its funding stream meant they picked up money to release albums when other, undeniably better musicians further afield, just weren't in the running.

More than once these enthusiastic younger players were described as having a default position of untutored Dixieland strut.

And sometimes that was true.

The PAG were David and Anthony Donaldson, Neill Duncan, Stuart Porter and David Watson.

The PAG were David and Anthony Donaldson, Neill Duncan, Stuart Porter and David Watson.

They appeared on their own albums and also in different configurations as The Black Sheep, Jungle Strut, Rabbitlock, The Family Mallet . . .

They were very much a group of constantly moving parts.

The Big R, by Primitive Art Group, 1984

The many albums from Braille are among some of my most treasured albums of that era. And they are challenging even today.

The many albums from Braille are among some of my most treasured albums of that era. And they are challenging even today.

This well researched, scrupulously documented account provides greater and more detailed context of these singular figures, the scene that grew up around them, the windy city in all its seediness during those years, the tetchy politics of the day (pre and post Springbok tour) and the music made, sometimes clinging on by the skin of its teeth as anarchy beckoned.

Perhaps the problem that those outside the city had with this music is that it was often labelled free jazz or simply jazz, but the more accurate description would be improvised music because it rarely touched on the embedded reference points of those musics.

These were largely self-taught performers -- some with more musical knowledge than others -- who started by simply having a go, but who over time refined, focused and came to a greater understanding of their potential.

These were largely self-taught performers -- some with more musical knowledge than others -- who started by simply having a go, but who over time refined, focused and came to a greater understanding of their potential.

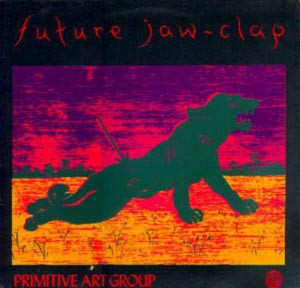

The point about PAG, as its members say in these pages, is that they were searching -- not to copy other free jazz or improvising musicians they'd heard on a few imported albums -- but to be themselves.

Beban's book has a kind of improv quality itself, like a voyage of discovery in the manner the musicians felt their way into what they became.

It neatly starts with the final PAG concert at the Michael Fowler Centre in March 1986 when the venerable but staid jazz aficionado and radio host Ray Harris found himself reluctantly introducing a group whose music he admitted wasn't to his taste. Only to find the crowd were very much on the side of these upstarts.

The story then goes back to origins through conversations with the PAG musicians, their formative influences, how they washed up in Wellington, what the city was like at that time (mid to late Seventies) and something of their current lives.

Beban paints clear pictures of the milieu (supported by well chosen photos) and those who weren't there – myself included – get a real feel for the people and the times.

The words evoke the music of these non-musicians who knew what they wanted to do, inspired by a few key albums like the Art Ensemble of Chicago's Fanfare for the Warriors and Ornette Coleman's early recordings.

The times were repressive – the Muldoon era – but the music they heard was liberating and through coalitions of artists, dancers, musicians, poets and fellow travellers something began to take shape.

Mr Chowmondley by the Family Mallet (Braille, 1986)

Beban's structure is like a jazz or improvised piece of music: characters are introduced one at a time – stepping into the spotlight for their solo as it were – and the writer captures their spirits, idiosyncrasies and opinions in colourful, evocative interviews which place the players into their context then and now.

The reader is therefore lead into cold rooms, performance spaces, abandoned warehouses, political meetings and rehearsals.

The reader is therefore lead into cold rooms, performance spaces, abandoned warehouses, political meetings and rehearsals.

This is a tiny group of like-minded individuals finding each other in a city which is grim and cold.

“In Wellington there was no one else to play with, there was no getting away from the others,” says David Watson.

“You might feel like it from time to time but there was nowhere to go,” he says, likening PAG to Pere Ubu in Cleveland.

“In a bigger town [Pere Ubu] would have separated, but partly the size of the town meant they stayed together and that's why smaller towns often produce really interesting bands.”

Wellington was that small town surrounded by suburbs crawling up hills. PAG were in the centre of the town and slowly, inevitably, their creative impetus drew others to them.

They performed in available spaces, on anti-tour protest marches, eventually recorded two albums and -- as with the others spin-offs on Braille – did their own artwork.

The smallness however also meant that as others moved into their orbit some of the musicians hooked up with them, so Braille grew and, where once there had been a vague consensus, new musical directions – some more free, others more notated – emerged. People came and went.

Beban recounts all this in detail, musicians are quoted, reviews cited and the social context acknowledged.

After PAG broke up the other unit emerged, most notably Four Volts, then Six Volts whose music reined in the extreme abstract nature of PAG but retained the quirkiness.

They adapted popular songs – like Led Zeppelin's Black Dog – which is something the more pure improvisational PAG would never do.

Black Dog (1989)

Six Volts became very successful and moved into cabaret.

Some in the PAG/Braille orbit left town and the country, others formed profitable careers like Plan 9 doing film music.

Through these pages there are many fascinating fellow travellers: Gerard Crewdson, Pamela Grey, Harry Sinclair, early champion/journalist Gary Steel, Don McGlashan, Bill Direen, Free Radicals . . .

This is a superb book about a moment in time when the outsiders found themselves alongside other like minds and creative spirits and through determination and sheer stubbornness made something unique, exciting and challenging.

The Primitive Art Group and the Braille Collective artists were part of something, but they also knew – and were told often enough by jazz musicians and some critics – what they were also not part of.

And that gave them strength.

“We didn't think of ourselves as jazz musicians at all,” says Anthony Donaldson. “That was something else, that was the Rodger Fox Big Band. We definitely weren't part of that.

“We really did not think of ourselves as jazz musicians. That was something that people always assumed we were, and it seemed difficult to deny, and pointless to deny . . .”

“I used to call it punk because there was a lot of punk in it,” says Stuart Porter.

“I used to call it punk because there was a lot of punk in it,” says Stuart Porter.

“To me it seemed more akin to punk than jazz, because we were just making it up, we didn't really know our instruments . . . there was a recognition that creativity and experimentation and doing something different was a common link between all of us”.

For what it's worth, in 1984 I launched a magazine: it was Passages; The Magazine of Jazz and Elsewhere.

The Primitive Art Group and Braille releases were reviewed in our pages.

They were the “elsewhere”.

.

FUTURE JAW-CLAP by DANIEL BEBAN VUP $50

post a comment