Graham Reid | | 5 min read

Pamela Digby did not marry well but she did, in a way, marry wisely.

Everyone warned her off Randolph whom she had only been with a few times before she agreed to his proposal.

Both wanted marriage: she because as a plain, dumpy redhead who had been passed over in her coming-out season; he because with the war coming he wanted to sire a son before he was sent off.

Randolph was a boorish, arrogant, entitled and argumentative drunk who was also a feckless gambler with an uncanny ability at losing. He was a notorious philanderer who leeched off his parents.

But he had a name.

He was Randolph Churchill, son of Winston who was soon to become British prime minister.

He was also often absent – at his club, with one of the mistresses, the army – but Pamela did give him a son.

She was now the daughter-in-law of Winston and the mother of another Winston.

Churchill senior and his wife Clementine loved Pamela who quickly became the old man's confidante and – although self-educated and largely deprived on social contacts as young woman – she was a quick study: she learned how to read people, flatter and seduce them, get them talking and be the perfect hostess.

Churchill senior and his wife Clementine loved Pamela who quickly became the old man's confidante and – although self-educated and largely deprived on social contacts as young woman – she was a quick study: she learned how to read people, flatter and seduce them, get them talking and be the perfect hostess.

And that was where she came into her own.

When war was declared and during the Battle of Britain she shipped off the baby Winston to the country or into the care of friends and hosted various salons where well-positioned and important public figures, American diplomats and military leaders, would gather to be wined, dined and given the opportunity to talk in confidence.

And Pamela would stroke their arms and egos – they were all men – and then report back to Winston what she had learned.

She was fearless and unflappable when the bombs fell and many of the men fell in love with her.

And so began a lifetime of seduction (she had numerous lovers), elaborately planned parties and soirees, gossip and Pamela Churchill trading off her husband's name to position herself in society and politics.

There's no doubt she was exceptionally bright and seductive or that her parties were places where all the important figures wanted to be. During the war a cast of diplomats, Hollywood stars (serving in the US forces), politicians across the spectrum and landed gentry all paid their respects to this woman who became increasingly glamorous and desirable.

A cost was paid by the young Winston who seemed to rarely see his mother but money took care of that.

Over the decades Pamela's admirers furnished her with apartments, cars, jewellery, fine art and more.

Was she an important figure in Britain at the time for her service to Winston senior and in bringing American and British together?

Was she an important figure in Britain at the time for her service to Winston senior and in bringing American and British together?

The answer is qualified and while there's little doubt she served a greater purpose than just her own, author Purnell – who wrote the excellent A Woman of No Importance about the spy Virginia Hall – perhaps overstates Pamela Churchill's role.

As she says in passing of her politically significant “strategic sex life” that “we will never know exactly what she told to whom. We will never know how these crucial transatlantic personal connections – so easily underrated – would have developed without her special brand of contact”.

We do know that Churchill senior valued her, as did his wife Clemmy. She was more favoured than their own children, certainly above the shiftless Randolph.

Pamela Churchill was an ambitious political animal at a time when women were invited to leave the room after dinner so the men could speak. She went along with it out of courtesy but left to her own devices was very much part of that world.

She knew official secrets and was one of the few who could say she had met Hitler (before the war, she was unimpressed by his small stature and nervousness), sat with Winston as a confidante and travelled with him, knew the politics of the day (recognising the American's shift toward a Cold War footing against the Soviet Union post-war) and – when she went to live in Paris after the war – ran simultaneous circles of diplomats, cafe society people (among them the disgraced Windsors) and intelligent women.

And she was still only in her late Twenties.

She could have been a lady of leisure and lived off her wealth, but she wanted to be part of the changing world and if possible – especially in regard to avoiding another war – to help shape it.

There were fallow years, the constant irritation of Randolph (they divorced early on), lovers like the married US diplomat Averell Harriman (who she would marry decades later) and Italian industrialist and Fiat supremo Gianni Angelli.

This is a world of improbable wealth: skiing in the Alps, sojourns on yachts around the Med and the chateau at Cap d'Antibes which she rented for four months every summer. And more.

It seems everyone of importance from British PM Anthony Eden, Joe Kennedy and his clan (including JFK and Jackie) to Aristotle Onassis, Hemingway, numerous counts and countesses, publishers, newspaper owners and editors, the elite of Hollywood (when she married Broadway producer Leland Hayward) and Truman Capote moved through her world, and she through theirs.

It seems everyone of importance from British PM Anthony Eden, Joe Kennedy and his clan (including JFK and Jackie) to Aristotle Onassis, Hemingway, numerous counts and countesses, publishers, newspaper owners and editors, the elite of Hollywood (when she married Broadway producer Leland Hayward) and Truman Capote moved through her world, and she through theirs.

Capote would, of course, later skewer her as one of “the swans”. He saw the chiffon not the steel.

The story of Pamela Churchill Harriman is as remarkable in her final decades as during her wartime in London.

She relocated to Washington DC when she married Averell Harriman after the death of Hayward and became a central figure in beltway politics, hosting parties and fundraisers for the Democratic Party (then on the slide) and used her Churchill name and connections to bring together politicians from both sides of the house. Often in the room where Van Gogh's White Rose hung.

In 1980 she was named Democratic Woman of the Year. One of her soirees raised $US3 million for the party.

If the Kingmaker title of this book feels like over-selling in its first half then it earns it when she is in the world of Henry Kissinger, the Carters and Bill Clinton of whom she was an early supporter and raised significant funds to propel him to the White House.

She remained the poised well-groomed hostess but as Gloria Steinem approvingly noted, she was “the woman who proves that not all feminists have to wear combat boots”.

She was charming but it's hard to warm to her on the page: her son Winston with justification felt pushed away as a child (he sounds as boorish and as entitled as his father), she was indifferent to the feelings of the wives of the men who fell in love with her and ended up in her bed, she bought affection from step-children and had her own affections bought by gifts of such jaw-dropping value we cannot begin to comprehend.

However not many people – it is impossible to think of another – met Hitler, knew Churchill intimately, counted French presidents and Lauren Bacall among their friends, won over Raisa and Mikhail Gorbachev (Raisa preferred to a long personal meeting with Pamela than with Nancy Reagan), travelled to Russia, Georgia and Kazakhstan for meetings (in her early Seventies) and was made America's ambassador to Paris by Clinton.

She knew Mandela, Joe Biden, Dennis Hopper, Sinatra, Christian Dior, Nixon and de Gaulle.

The Honourable Pamela Harriman died in Paris in February 1997. The man who tried to revive her with oxygen was Henri Paul who would later drive Princess Diana into that tunnel.

Even in death, she seemed to touch fame and infamy.

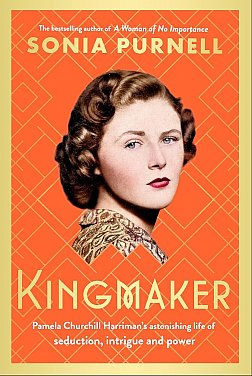

Kingmaker, subtitled “Pamela Churchill Harriman's Astonishing Life of Seduction, Intrigue and Power” is indeed fascinating.

Come for the war years . . . but stay for the decades in DC and Paris.

“Astonishing” seems an understatement.

.

KINGMAKER by SONIA PURNELL Virago $35

post a comment