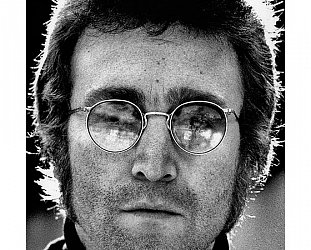

Graham Reid | | 8 min read

It was an afternoon in June 1846 when Charles Dickens finally broke the writing block which had been troubling him.

It had been two years since his previous novel, but these last weeks walking in the hills of Switzerland above Lausanne had allowed him to sketch out the framework of a book.

In his study overlooking the lake, Dickens – a man of curious personal superstition who preferred to be away from London on the publication of any new work – took out a copy of Lawrence Sterne’s Tristram Shandy, randomly pointed to the printed page and read: “What a work is likely to turn out! Let us begin it!”

And so prompted, he began what was to become Dombey and Son, published in monthly parts from October through to April 1848.

Yet in this writing, as with many of this works, his own life imposed itself. While working on the eighth instalment back in London, Dickens was thrown by a horse and was so shocked by the incident which occasioned “a nervous seizure of the throat” that he travelled to Brighton to recuperate and work on the next part of the book – a novel in which Mr Dombey is thrown from a horse and kicked senseless.

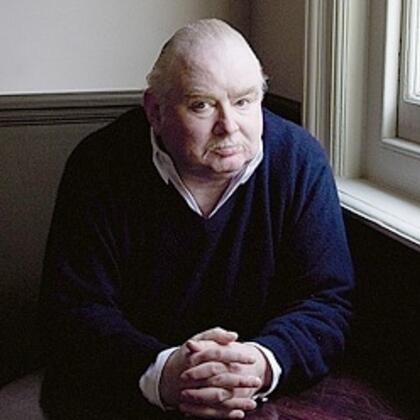

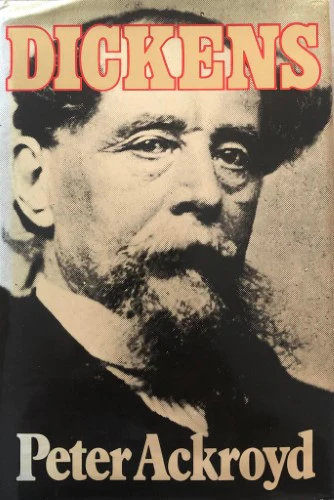

That Dickens wrote much of himself into his books is a view shared by all his biographers, yet Peter Ackroyd exhaustive new analysis, Dickens, scrupulously pursues the idea as it unearths and sifts the minutiae of the writer’s life. For a man of considerable self-discipline and meticulous order, “who ran his life like a military campaign,” Ackroyd says, this was Dickens’ way of controlling the world.

“Dickens was a man who found it very difficult to distinguish between fiction and reality,” says Ackroyd from his London home. “Throughout his life he interpreted events in terms of his fictional imperatives.

“One of the reasons I wrote such a detailed book was because I wanted to find the exact moment, the day, the week of certain events so I could see the passage between the life and the work and vice versa. The boundary between his life and his work was very thin.”

“One of the reasons I wrote such a detailed book was because I wanted to find the exact moment, the day, the week of certain events so I could see the passage between the life and the work and vice versa. The boundary between his life and his work was very thin.”

To write in such a detail Ackroyd has produced a book of closely reasoned analysis, solid research, but much speculation. And, inevitably, considerable bulk. The size sometimes obscures the scholarship.

“Peter Ackroyd’s leviathan of a biography runs to 1195 pages, tips the scales at 3lb 12oz and quantitatively and qualitatively gobbles up its rivals (none of them exactly minnows)," wrote Peter Davalle in the Times Saturday Review.

“Down they go into the belly of the Ackroyd whale; the lives of Dickens by E. M. Forster, Una Pope-Hennessy, Angus Wilson, Percy Fitzgerald...” And so on.

When faced with such notable and thorough predecessors, why Ackroyd should have set himself such an undertaking is difficult to fathom. Especially one which, by general critical consensus, reveals so little new about its subject. Yet it is also a controversial work.

In seven, very short, sections Ackroyd interpolates an imaginary meeting between Little Dorrit and Dickens, includes a dream he [Ackroyd] had about the writer and interviews himself about the difficulties of writing such a book.

He also engineers a discussion between Dickens, Oscar Wilde, Thomas Chatterton and T. S. Eliot, all writers Ackroyd written about in the past either in novelisations (Chatterton) or conventional biography (the Eliot won the Whitbread Prize for best biography published in 1984).

Some of the interpolations are undeniably clever. The exchange between Chatterton and Wilde allows this lovely piece of imaginary Wildean wit:

Chatterton: All around is anarchy and artifice and –

Wilde: Alliteration?

And later in the same sequence Dickens wishes William Blake (the English artist, writer and visionary who spoke to angels) would join them. Chatterton says he will be along shortly – and sure enough, Ackroyd’s new biography now being researched is about Blake. Cute perhaps, but harmless enough. Other sections offer fewer pleasures.

“I do not mind these interpolations,” wrote Ferdinand Mount in a largely favourable review in the Spectator, “except for the penultimate one, where Ackroyd has a rambling conversation with himself which is both banal and self-indulgent. When a biographer starts telling us he uses files and card boxes and indices we can only say: we don’t wish to know that, kindly leave the stage.”

Ackroyd simply says he wanted to write a very different kind of literary biography and notes that the revival in literary biographies of recent years has run parallel to a revival in literary fiction – to which he himself has contributed with Chatterton and The Last Testament of Oscar Wilde.

“Every biography is conditional and reflects the conditions of its time. Those interpolations would strike some people as post-modern and playing around with perspectives and in the future will be seen as part of this period.

“You can never really escape the condition of your time so you might as well embrace them and use the properly.

“When I had finished the very straight biography I knew there was something missing. I went on holiday and those passages occurred to me one after the other. I had no conscious control over them as it were – or even over the whole work.

“My decision to write about Dickens was prompted by intuition and impulse rather than rationalisation and the book proceeded with me almost standing aside.

“My decision to write about Dickens was prompted by intuition and impulse rather than rationalisation and the book proceeded with me almost standing aside.

“Although I separate fiction and biography I don’t think there’s much difference in the composition of the two.”

Ackroyd’s equal and prolific command of the genres of fiction and biography drew Anne Constable in Time to note that “no new biography of Charles Dickens should go unnoticed, especially when the writer is Peter Ackroyd, one of the most amusing and acclaimed young novelists on the British literary scene. Like Dickens, Ackroyd finds rest more exhausting than labour. He turned out two novels, Chatterton and First Light, during the five years he was working on the biography.

Busy, yes – and Ackroyd also started young. At eight he wrote a drama about Guy Fawkes.

Born into a working class family in East Acton, London in 1949, he studied English at Cambridge and later went to Yale University.

In 1973 he was literary editor of the Spectator and by 1977 its managing editor. In 1983 he quit to become a full-time novelist and biographer.

Ironically, he says he didn’t seriously read any Dickens until he left university. His first novel, The Great Fire of London, was about trying to make a film of Little Dorrit and his reading of that novel spurred his interest in the rest of Dickens’ fiction.

When he was a child his grandmother inculcated a sense of Dickens’ world into him as she took around “the darker, more ancient aspects of London which have a flavour and still linger today.” As a Londoner himself and a writer, the novelist cast a long shadow over him he says, but it was “as a presence rather than as in author” he says.

“When I sat down to write the biography I wanted to come to terms with that presence. My grandmother passed on impressions of an overwhelming sense of antiquity of the city and she was of that last generation to come from those conditions, the generation which would have thought of him as a realistic writer who spoke to them and their generation. They never lost contact with that vision he had given them of their lives.

“Dickens’ genius was to be the first urban novelist who knew London and make it the centre of his fiction.

“It is difficult to imagine any English speaking/English writing novelist who has the same capaciousness and breadth as he had, who combined comedy with pathos, theatricality with tragedy, symbolism with realism. That is a unique achievement – but he also came at the beginnings of modern techniques in printing and the growth of the middle-class audience which encouraged him. None of that can happen in quite the same way again.”

By taking as his brief placing the writer in the total milieu of his time. Ackroyd says self-discipline is a requirement for him to work. His day begins at 6 am. He diligently writes 1000 words a day (“a steady momentum is indispensable, persistence one of the most important qualities”) and prefers to run his fiction writing parallel to biographical research so he doesn’t go stale on either.

Writing is for mornings, afternoons for research and evenings for relaxation watching American soaps and quiz shows on television.

He has taken to television himself to promote both Hawksmoor and Dickens on The South Bank Show. He admits he is enjoying book promotion more and more although “it is a terrible suspension of activity to take two months off.”

When promoting Dickens he took a notebook with him to scribble out longhand ideas for his present novel project, although he obviously prefers to work in one of his two studies at his homes in London and Devon where he has identical word processors.

“I opened a bookshop recently but I don’t think I’ve kissed any babies,” he laughs. “I certainly like going into bookshops and meeting people at the rough end of the trade. It would be absurd of me to wash my hands of that and I was frankly delighted when Dickens sold a lot of copies.

“I was worried about the book. Not reviews, but sales because it was important for Sinclair-Stevenson that it was a success. Fortunately it worked fairly well from the beginning.”

That is an understatement; Dickens has been one of the publishing success stories of last year in Britain selling over 60,000 copies in the first fortnight. And that on a book with a cover price of $64.

John Lyon, sales director for publishers Sinclair-Stevenson, still sounded genuinely excited by the success of Dickens as he counted off sales figures and retailer reactions when he visited Auckland last month.

Here to meet with his company’s local distributors, Lyon concedes Dickens was “a dream start, a fluke” for a company only launched by old Etonian and former Hamish Hamilton editor Christopher Sinclair-Stevenson on September 3 last year.

When Sinclair-Stevenson quit to found his own company many of the authors he had encouraged (Ackroyd, William Boyd and Paul Theroux among them) followed him. Sinclair-Stevenson quickly raised initial capital of $7.7m and paid authors generous advances. Ackroyd was given $2.1 million for Dickens and his forthcoming Blake biography.

And Dickens was a literary publicist’s dream. Divergent reviews raised the profile of the author and the work. Anthony Burgess in the Independent praised the book “without reservation.” Eric Griffith in the Sunday Correspondent throughout it fat and dreary.

While the book may tell little new about Dickens – although no other biography brings such a wealth of information together in one place – Ackroyd does suggest that Dickens’ relationship with the young actress Ellen Ternan, for whom he left his wife and family and lived off and on with for many years, was chaste.

No previous biographer has suggested that and indeed a new book by Claire Tomlin, The Invisible Woman, a biography of Ternan, again advances the traditionally held view of the pair being partners.

“I don’t think it matters one way or the other whether he had sex with her or not,” Ackroyd says. “The truth is he had an obsessive relationship which lasted for many years. Whether it was sexual or not is beside the point.

“There is no doubt it was a very strange relationship and he seemed to be doing what he did throughout his life in times of crisis or emotional trauma. He would reach for his fiction to help him understand reality and his novels you have a recurring image of the idealised young virgin in a platonic relationship with an older man.

"There is no doubt in my mind that was the relationship he formed with Ellen Terman."

.

Also by Peter Ackroyd, his study of Venice.

post a comment