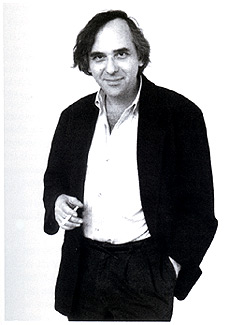

Graham Reid | | 9 min read

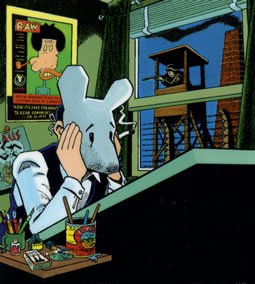

Art Spiegelman – like many authors one suspects – can’t resist looking for his book in stores. But the categories bookshops have are seldom very useful he says, and his book Maus, a 160 page paperback-sized comic, defies convenient pigeonholing.

Store owners think it is “humour” because it’s a comic (”people looking there certainly aren’t looking for something like Maus,” he laughs) and some shop owners can’t even decide whether it is fiction or non-fiction.

“It really derives me nuts when they put it under Judaica, says Spiegelman from his Lower Manhattan apartment which serves as office and workspace for Maus and his “sporadical” publication Raw.

But Spiegelman has the perfect solution to the problem of where to place Maus in shops: he got it from a New York bookshop which had given up even thinking about the problem. “They just kept it in new releases,” and I liked that. Others come and go, but Maus remains. That’s great.”

Of course, Maus is not new. In one form it began as far back as 1972 and then Spiegelman started printing chapters in Raw from 1980 to 1985. The following year the first six chapters were published as Maus. A Survivor’s Tale, by Pantheon and, more recently Penguin have picked up international distribution.

From the first, however, this very different kind of comic was winning high praise – and substantial sales.

Yet the story is a demanding one. In stark black and white Spiegelman tells the story of his father Vladek’s life in pre-war Poland, through the horrors of Auschwitz and the relationship between father and son in contemporary America.

Now translated into 15 languages – including German, Hebrew, Japanese and French – Maus incorporates a wry and perhaps useful distancing device. The Germans are drawn as cats, Jews as mice, and Poles as pigs.

Amidst the praise from opiners as diverse as The Wall Street Journal (“integrity on every level”), Newsweek (“uniquely moving”) and The New York Times Book Review (“an unfolding literary event”) the as-yet-incomplete story has been subject to the occasional dissenting voice.

Spiegelman adopts a thick, cynical tone which toughens his already taut New York accent. “People have said, ‘oh yeah, a comic book about the Holocaust with funny animals – swell, I can’t wait to see it, right?’ I can understand that.

“That response has to be with being unwilling to contest what I agree is a rather unsavoury sounding concept. The Holocaust hasn’t been talked about that much except as part of the creation myth for Israel.

“Yet the scars and impacts on psyches are here now and have been kept under wraps until recently.”

Readers of Maus can see for themselves where Spiegelman has been scarred. A grim four pages in the middle of the book, Prisoner on Hell Planet, was drawn in 1972 and was the writer’s attempt to deal with the 1968 suicide of his mother. Elsewhere in Maus he writes and draws openly of his time with a psychiatrist.

And between the flashbacks and cinematic shifts which the comic format allows we see the writer arguing with his frustratingly demanding father and debating the nature of his own work.

What keeps the attention of the reader as much as the format and narrative is the honest humanity of the characters? There are flashes of typically self-depreciating Jewish humour, the strained relationship between cantankerous father and son crackles with generational antagonisms and at one point Francoise Mouly, Spiegelman’s partner who is French, presents the artist with the obvious problem which he grapples with on the pages as to what kind of animal she should be drawn.

By working on many levels Maus confirms there are two survivors in the story: father and son each carrying their own tortures.

“I never really saw any other option for me that this would be harrowing to tell. But the idea of my own work has always been to dig as deep as I could and confront certain truths.”

Digging deeper has been a consistent feature of Spiegelman’s career from the time he was an underground artist in the burgeoning alternative “commix” scene in San Francisco during the late 70s.

It was at that time the word “commix” was coined to identify the new style. It is the word Spiegelman favours for his own work and particularly for Raw magazine. The comixing of words and pictures is clearly something separate from the more usual definition of “comics.”

His work appeared in a number of underground magazines of the period, but he grew disenchanted with the perception that commix were stereotyped as being part of declining hippie culture and dealing only with “sex, dope and cheap thrills.”

His work appeared in a number of underground magazines of the period, but he grew disenchanted with the perception that comix were stereotyped as being part of declining hippie culture and dealing only with “sex, dope and cheap thrills.”

In 1975 – along with Bill Griffith, creator of a famous comix cult figure Zippy – Spiegelman co-founded Arcade, a quarterly which aimed at a blend of high quality work and anarchic energy.

After two years Spiegelman was back in New York and again bemoaning the lack of opportunity for artists who commixed words and pictures.

With partner Mouly – an artist and architecture student from France – he co-founded Raw, a large format comix magazine which first appeared in July 1980. He was also working on Maus and each issue of Raw included an episode.

Spiegelman says he had a complete outline of Maus in 1978 and “with some deviation” has kept close to that original scheme. Where he has departed is something very apparent as the evolving narrative of Maus kept space with it some changing emotions.

At the beginning of Chapter Eight, Time Flies, published in Raw last year (and after the hugely successful collection of the first episodes of Maus into one volume) Spiegelman shows himself not as a mouse but as a man in a mouse mask.

It was time when he was questioning the whole conception and confronting four serious offers to turn his book into a TV special or a movie.

As the frames of the story continue, Spiegelman shrinks in size and goes to his psychiatrist.

In retrospect he sees those lining frames as the breakthrough he needed at the time, making it possible for him to find his way back into the story and to continue.

And Maus is now “on the home stretch.” Two short final chapters will appear in the next issue of Raw to be published in June and he is also considering a short epilogue.

Once again the chapters subsequent to the first six which appeared in paperback will be collected; Spiegelman says he always envisioned Maus as two separate volumes.

With its even more daring juxtapositions of time, disturbing metaphors and inventive visualisation, it is possible to anticipate some of the favourable critical commentary even at this point.

Alongside the growth of comix as a unique art form has grown a school of critical and informed opinion.

Back in 1974 Spiegelman noted: The comic strip is barely past its infancy. So am I. Maybe we’ll grow up together.”

With the publication of Raw Spiegelman and Mouly extended the boundaries of possibility for the art form and found themselves in the vanguard of criticism and comment.

Although he teaches at New York’s School of Visual Arts and is in demand as a speaker on the college circuit, Spiegelman has mixed feelings about the value of teaching courses in comix – although he cheerfully admits that their existence has sometimes kept Maus alive. “Every September there is a big surge in sales.”

By placing comix in an academic context he feels that they become harder to locate (“for years I thought Mark Twain was boring because you had to read him in school”) yet also acknowledges the iconoclastic approach of “if it’s in school it sucks” isn’t satisfactory either. Schools and teaches can raise awareness of the medium although in his experience students still have a poor degree of literacy in the style.

With the publication of Maus in many languages he has observed some interesting variations in response from readers. “I had this one great question when I was in Germany. ‘What kind of animals would you make Austrians if you were to put them in your book?’ I pointed out Hitler was Austrian and I’d drawn him on the cover as a cat so they could figure that one out.

“In reviews I’ve seen very different biases. In Germany the big one is, ‘is it correct?’.

“It’s not that didn’t come up in America – if just had a different emphasis and certainly wasn’t an issue of the same intensity as in Germany.

“In Israel the issue had more to do with generational conflict. And in France there was a great deal of literary about the medium itself.

“When it came to simply dealing with the medium of comix in the States reviewers would say ‘My God, this is a comic strip. But yow! It’s not what you think’ Then they’d be able to get onto what it was about. That wasn’t even an issue in France.”

That degree of visual literacy combined with a more European attitude (“they are more culturally relaxed about sexual matters and less puritanical than Anglo-Saxons”) informs the pages of Raw which deliberately adopted a large format when it first hit bookshops in mid 1980.

From that first issue, billed as “The Graphix Magazine of Postponed Suicides,” Raw broke new ground.

Large colourful pages lay alongside almost Cubist designed black and white artwork; there would be pages of text and surreal storylines.

And it was international. Contributions came from artists in Paris, Barcelona, Philadelphia, Brussels and Canada.

Strips by Windsor McCay from 1906 and French artist Caran D’Ache in 1897 were bound in the same covers as the high realism of Josh Alan and Drew Friedman’s parody of a racist Andy Griffith Show where the citizens of Mayberry lynch a black travelling salesman.

Now Raw is signed up with Penguin, and what was once in the left-field is part of the mainstream or is it?

The first Penguin issue was much criticised in comix circles. Instead of the customary large-format it came out in paperback size and some commentators were quick to wonder just how much Spiegelman and Mouly has sold out.

The decision for the new small format was made before signing with Penguin and for two clear reasons he says.

Partially, boredom with working like crazy to produce something which looked like what they had done before; but also the smaller format allowed them to publish a number of the longer stories is they had been collecting.

“Connected with that, at least form our view from Lower Manhattan, it seemed Raw’s larger format had won its particular battle. Prior to Raw comix seemed dismissible, then all of a sudden people were seeing them as Art.

“But that they meant visual art because Raw made you slow your eyeballs down to absorb it. However there wasn’t that much feedback on the specific content.

“On Maus though, I had a lot of feedback on content because the small size, focused attention on it. We always wanted Raw to be a visual literary magazine, to get people to notice the words aspect of that co-mix of words and pictures.

“We were also curious to see how visual you could make a small magazine. In its large size Raw forced attention from the reader.

“In a way the large format became too easy.”

The small size allows its editors to include more material, and Spiegelman is glad of the chance to include co-mixers from the past – not so much to create or acknowledge ancestors, he says, but because their work is still vital.

“But most people’s history goes back about 10 minutes and until recently it was very hard to find early Krazy Kat, for example.”

The next issue of Raw will include a 32-page reprint of an old Krazy Kat along with a Gustave Dore strip from last century “about being a cartoonist.”

Spiegelman’s editorial decisions do not always please everyone and a recent article in the British Sunday Times huffed about one particular strip which features some graphic sexual content.

Spiegelman acknowledges that his taste may not be everyone’s but concedes certain difficulties.

“Banal sexism which doesn’t go all the way to misogyny is a problem, bland racism which doesn’t go all the way to misanthropy is also a problem. We prefer things which are neither.

“What is interesting now is that the shell has been cracked and anything is fair game. Any theme available to any medium is now available to comix and that includes, of course, pornography at one end, political tracts at the other and everything in between.

“I can see there is room for politically incorrect thinking (in Raw) as long as it has that rolling intensity that keeps it alive.

“In America, however, we are going through a very glum time with the censorship of [the rap group] 2 Live Crew and the Mapplethorpe exhibit. It does seem peculiar however that the same alarms don’t go off with people when some of the things comix deal with are set in type.

“But, if we’re being written about indignantly in the Sunday Times I‘m sure that’s healthy.”

post a comment