Graham Reid | | 8 min read

LKJ: Come Wi Goh Dung Deh

They were the happiest days of my life, the poet recalls as he sits in winter-blown London.

"I was born in a little town called Chapelton in rural Jamaica," he says with what could pass for wistfulness.

"My parents were peasant farmers and my mother went to live in Kingston and eventually came here. During that time I stayed with my grandmother. I loved the country living. We had no street lights or electricity, no radio or TV, but we still had a great time."

Linton Kwesi Johnson -- today known as a political activist and unofficial poet laureate of London's predominantly black suburb of Brixton -- grew up helping with the sugar harvest and listening to local folk songs and stories about duppies (ghosts). He attended the local school with its colonial curriculum and was a fast learner.

"The standard of education was far superior to what I was confronted with in south London when I came here at 11 to be with my mother. I got the school prize for maths in my first year because I was so far ahead of the other boys."

For Johnson, an enthusiastic student, the beat of Brixton's streets was very different from the rural roads of his childhood. From banana plantations to concrete walls, simple folk songs to ska and rude-boy reggae, green fields to grey tenement blocks.

He encountered racism in the playground, so by his mid-teens developed an interest in black political movements. He joined the British Black Panthers, discovered black literature and began to write politically charged poetry full of incendiary fury.

"In those days we were trying to bring poetry back to the people and a lot of it was in a political context and of political relevance, which shows culture is not just about art but about life. There were a few poets around like Roger McGough, Adrian Henri and those guys."

But Johnson's poems were different from those Liverpool Poets who emerged from the mid-60s fascination with the Beatles and their milieu. His poems were published in Race Today magazine and were notable for his use of the speech rhythms and pronunciation of Jamaicans.

His poem Yout Scene, which opened his '75 collection Dread Beat and Blood, was typical: "last satdey/I neva dey pan no faam/so I decide fe tek a walk/doun a Brixton/an see wha gwane ... "

What was going on in Brixton in the mid-70s was a consciousness uprising through music, politics and anger. Johnson, by this time with a sociology degree behind him, and the C. Day Lewis Fellowship as writer in residence for Lambeth, took poetry and politics to his people in a form guaranteed to get attention. He put it to music.

The late 70s witnessed the extraordinary collision of reggae and punk. Bands like the Clash and the Ruts bannered the importance of the reggae outlaws and there were numerous cross-cultural connections, many of them fuelled by anti-Thatcher rhetoric and huge unemployment among the disenfranchised young and the swelling black population.

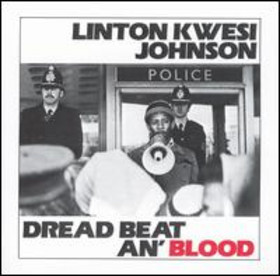

Johnson's 78 debut album, Dread Beat and Blood, came out on the Virgin Frontline label -- the label logo was a black fist grabbing a piece of barbed wire -- under the name Poet and the Roots. It was a thunderbolt of lyrics set to appropriately brooding reggae which put Johnson alongside Bob Marley as the most powerful voice in reggae.

On the back cover the diminutive Johnson is pictured with a megaphone, flanked by huge bobbies, at a demonstration outside a police station.

Equally strident albums followed -- on his third album, Bass Culture, he railed against the death of expat New Zealand schoolteacher Blair Peach who was killed in an anti-fascist demonstration -- and he was in tune with the spirit of his times: the Toxteth riots of 81; the flourishing poetry scene which included John Cooper Clarke, his Jamaican contemporary Mutabaraka, Attila the Stockbroker and others; anti-Thatcher demonstrations; and protests against the brutality of the SPG, the police's Special Patrol Group, which was notorious for targeting black youths under a stop-and-search policy based on suspicion ("suss").

"De SPG dem are murderahs/we cyan let dem get no furderah."

On the frontline, often literally, was Johnson. He was arrested, accused the police of being fascists to their faces, took potshots at white liberals and the Rock Against Racism organisers ("We don't rock against racism, we fight it") and had little time for middle-class or upwardly aspirational blacks who didn't join the struggle (namely his poem De Black Petty Booshwah.)

In the mid-80s he retired from performances -- "I was tired of being on the road and was needed at home base, and it allowed me to have more time to write". But today at 51 the poet and activist is as busy as ever. Since the early 80s he has run his own record label, so admits some days he's simply doing business at his desk.

"I'm an occasional writer [of] verse and not a professional poet in the sense of people who devote their lives solely to the pursuit of the muse. Occasionally I'm asked to review a book ... and I get the odd commission. I can get more work if I want it but it doesn't pay well and I have other things to be getting on with."

Some of that is the business, but the struggle continues.

"Yes, it's what it has always been, the struggle for racial equality and social justice. That can manifest itself in lots of different ways, whether it's getting involved in a campaign for justice for someone who has died in police custody or whether it has been at the George Padmore Institute [a Brixton-based organisation established in 91 of which he is a trustee].

"It has a 50-year archive of the black struggle in this country. It's a library and research institute which organises talks and seminars. Those things are all part of general ongoing activity."

While Johnson was an activist at the barricades, he also never denied he came from an academic world. During the 80s he worked in journalism at Race Today, was a reporter on Channel Four's race relations programme The Bandung File alongside activists such as Tariq Ali and Darcus Howe (to whom he had dedicated Man Free on his debut album), and has picked up numerous honours. He was made an associate fellow at Warwick University in 85, honorary fellow of Wolverhampton Polytechnic in 87, received awards from Italy for his services to poetry in the 90s, and 18 months ago a collection of his work, Me Revalueshanary Fren, appeared in Penguin Classics editions.

But Johnson did not mellow. He continued to record and read his poetry and his '99 album Tings and Times featured a big jazzy band. But throughout, his rage at injustice is undiminished.

"New Labour is a continuation of Thatcherism both in domestic and foreign policy, so people voted for the Labour Party and got a Tory government. That's one of the peculiarities of politics globally now. After the fall of communism, politics shifted towards the centre and there are very few centre-left governments around."

But a lifetime of activism has had its payoffs. There has been immense social and cultural change in Britain since the mid-70s, especially in Brixton.

"I walk down those streets nearly every day. The first change is you notice is on Railton Rd. A lot of the old slum houses are gone after the 81 riots and there's an adventure playground on one side of the street.

"I remember when black families would live in one room. Now people own their own houses or council housing. It's not uncommon to go to a court and see the prosecuting lawyer is black and the defending lawyer is Asian or black. We have our people in Parliament and even a Government minister, so that's a measure of how far things have changed."

But the struggle continues because some things don't. Johnson identifies racism in the police force -- recently exposed in undercover filming by the BBC -- and the institutional racism that exists in some of the arms of Government.

"That's an ongoing problem, but now we have the first black chief inspector [Deputy assistant commissioner Mike Fuller, appointed last September] and that would have been inconceivable 30 years ago.

"So yes, tings and times have changed and we have won a lot of the battles we fought. But the struggle for social justice and equality is protracted and ongoing."

He cites the problems faced by recent immigrant groups struggling to find their place in Britain. What these communities lack -- although he wouldn't say it -- is a voice like black communities found in Linton Kwesi Johnson, a man who mobilised words and put them on the streets.

"I'm looking forward to having the poetry heard in New Zealand without the music because it began with the word. Everyone knows me as a reggae artist, but the word is important."

With his schedule of readings, running an independent record label, work with the Padmore Institute, and family life (he is a recent grandfather), the long-cherished dream of retiring to Jamaica, a country he visits regularly, seems elusive.

"Easier said than done," he laughs. "I've kind of modified my outlook and am thinking the ideal would be six months here in summer and the winter months back there. I'd like to do that but ... well, there is still work to be done."

post a comment