Graham Reid | | 2 min read

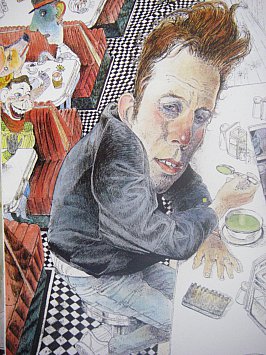

The musical journey of Tom Waits -- from bohemian barfly poet with an affection for the Beat Generation and Raymond Chandler to the clank’n’grind noir-noise of his more recent albums -- has been one of the most rewarding in rock culture.

Although immediately that needs qualification: Waits has been of rock culture but never part of it. As Luc Sante of the Village Voice notes here, Waits cobbled together a surreal amalgam of country’n’western, French chanson, New Orleans jazz and sea shanties -- but his jukebox never carried much youth culture.

From early albums where he married tales of waitresses and bourbon with string sections through his narrative trilogy in the mid 80s (the albums Swordfishtrombones, Rain Dogs and Frank’s Wild Years), his digressions into soundtracks (One From the Heart, Night on Earth), and theatre pieces (The Black Rider with Robert Wilson and William Burroughs, Alice and Blood Money with Wilson), Waits has stood apart from his contemporaries and carved his own wayward path.

The break from his increasingly cliched image as the boozy lounge singer came with that extraordinary trilogy where he abandoned piano, strings and whiskey-soaked sentiment for guitar, bullhorn and uncompromisingly aggravating percussion. He went from Beat to beats.

It was a beautiful noise, but noise nonetheless.

Attempting to follow Waits’ idiosyncratic progress were hapless journalists who would find their man equal parts evasive and illuminating in interviews which, at Waits’ suggestion, were conducted in seedy bars or low rent diners during which the singer would wilfully subvert the situation by pulling out bewildering facts in the manner of a carnival huckster. (“There are 35 million digestive glands in the human stomach.”)

All this added to his allure and helped draw a veil over the very private life of Waits.

From this collection of interviews, album reviews and think-pieces we learn only that he married scriptwriter Kathleen Brennan in 1980 and has collaborated with her ever since on his albums, they have three children, and live north of San Francisco.

We also learn Waits was the son of school teachers (he may or not have been born in the back of taxi), and that many journalists want to try their own style of Beat writing when pulling their articles into some kind of shape.

That is not to say this collection isn’t illuminating. Certainly there are some pieces which are perfunctory, especially those from his early years, but Waits’ ideas flash through in single sentences (“My career is more like a dog, sometimes it comes when you call”) or in revealing encounters with trusted friends Elvis Costello, film-maker Jim Jarmusch and Wilson.

Unfortunately some pivotal moments go unrecorded -- his soundtrack to Francis Ford Coppolla’s One From The Heart gets scant attention, his stage play Frank’s Wild Years is also passed over -- but as the chronological collection gains pace Waits drops some of the masks and consistent threads are apparent.

He has been unwavering in railing against musicians who sell their music for use in commercials. He launched and won his first lawsuit against a sound alike ad for Fito-Lay potato chips in 1988 and has taken similar action against others who have adopted his sui generis style -- it is possibly to describe a song as Waitsean -- to flog products from jeans to automobiles.

Difficult though his music has sometimes been (despite him always crafting heart aching ballads) Waits has latterly managed to find a receptive audience.

His 99 album Mule Variations (which to this writer sounded like a calculated compilation of previous styles) was his biggest seller and won him a second Grammy. The first was for Bone Machine in 92 which won best alternative music performance which he hated: Alternative to what? he raged.

Waits’ lengthy career -- 35 years now, he is 56 -- is not as haphazard as it may have sometimes appeared and this collection usefully joins the dots between his many styles and personae, and his stage and film career, and offers a sense of coherence that might have sometimes only ever been apparent to the amusingly elusive Waits.

But the man remains an outsider and for many will always be an acquired taste.

Of that, the most apt opinion here comes from Robert Wilonsky of the Dallas Observer in a phrase Waits might have used himself: Either you like the sound of a barking dog, or you buy yourself a cat.

post a comment