Graham Reid | | 8 min read

John Lennon -- who would have been 68, had he lived, at the time of this pubication -- did not have an unexamined life. In countless hours of drugs, meditation and therapy he analysed himself. Through many thousands of interviews -- some brutally honest, others self-mythologising -- he gave others material to scrutinise his life in intimate detail.

He has been central in books by his half-sister, first wife (two), tarot card reader, personal assistant, lover May Pang, and many others. Some have focused on his politics, others on his art, some even on his music.

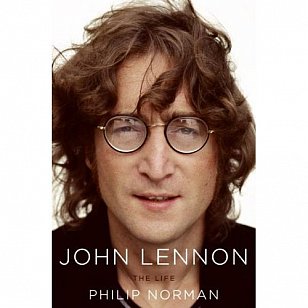

So another biography -- even one titled with a confident definite article -- would seem a book too far.

Yet as author Norman -- who has previously written well about the Beatles and Lennon (Shout! and Days in the Life) -- notes there have only been two Lennon biographies since his murder in 1980, one the scurrilous The Lives of John Lennon by Albert Goldman which was the size of a brick.

As if to restore balance, Norman’s tome sits on the scales with similar heft.

With the initial co-operation of Lennon’s second wife Yoko Ono and remarkable access to family, letters written by his Aunt Mimi, schoolboy friends, a very candid George Martin, his son Sean and many others who have seldom, if ever, spoken about Lennon, Norman has pulled together an insightful, unflinching and in many places remarkably fresh look at a man whose music, image and influence commanded headlines for two decades.

This crisply written account places Lennon in the context of his changing times: the austerity of post-war Britain, teddy boy’n’skiffle years, Beatlemania, benign drugs and on to the political activism of the volatile 70s.

Lennon’s life reflected all these periods, yet Norman also offers amusing and sometimes telling insights (he grew up with his Aunt Mimi who wouldn’t have a record player in the house) and the result is a rounded portrait of this man who could, on the same album, offer a paean to peace in Imagine and a withering personal assault on his estranged friend Paul McCartney.

From his teenage years until his Thirties he was suspicious, rarely affectionate, flirtatiously suggested he was bi-sexual and was clearly a flawed and troubled man full of anxieties, alarmingly violent jealousies and possessiveness when it came to his girlfriends and wives, and prone to often crippling self-doubt.

Norman’s analytical and detailed account traces all that back to his childhood which is here, for the first time, fully revealed.

In previous accounts Lennon’s father Freddie (actually “Alf” to the family as Norman reveals) has been the absent figure but this book brings the Lennon side of the family back into the picture, and fascinating they are: Lennon’s grandfather (also a John) had a gift for music and comedy, left Britain and toured in America in a minstrel show and passed on his musical skills (and the distinctive Lennon nose) to his children, among them Alf/Freddie who also fancied himself as an entertainer.

Norman gives the lie to the story that Alf abandoned Lennon’s beloved mother Julia (he comes out rather more noble despite his many shortcomings) and in this telling it is Julia who is flighty, sexual promiscuous and immature.

That Lennon loved his mother is beyond doubt, but he was also drawn to her sexually and recalled an incident as a teenager when he was lying next to her, touched her breast and wondered if “I should do anything else . . . Presumably she would have allowed it”.

What that tells you about how he perceived his mother is alarming. And his sexual desires -- from masturbation sessions with childhood pals and Paul McCartney to his concerns that Yoko had lost her drive in their later years together -- saturate these pages.

But so does his humour and creativity, especially when he went to live with Aunt Mimi who appears as an even more formidably intractable woman than she has in previous accounts. She also remained a virgin until late in life and an affair with a young lodger, despite having been married to John’s “Uncle George” for many years.

This biography is full of such fascinating detail, but much of it about Lennon is also revealing.

The “working class hero” was brought up a happy, polite, middle-class boy in a loving and orderly household, and spoke the Queen’s English. (As a teenager he adopted the nasal Liverpool accent to annoy his Aunt Mimi who raised him, and retained it into his public career.)

But the disappearance of his father, the death of his mother when he was 18 and that of Uncle George and his close friend Stuart Sutcliffe all soured him. Anger drips from these pages, much of it directed at women and the weak. His drawings as seen in his two slight books In His Own Write and Spaniard in the Works (published in his early Beatle years) could be cruel.

In the absence of leadership he became a leader, ambitious for his band but also prone to bouts of sullenness if things didn’t work out.

That seems to have sapped his energy and even in the mid-years of the Beatles fame he started to write less and became increasingly withdrawn. This perhaps explains why he often meekly followed leaders like the Maharishi, primal scream therapist Arthur Janov, Yoko Ono (who clearly liberated him from his creative slumps and fed his notion that he was a great artist), yippies . . .

The book hits more familiar territory in the Beatle years -- raging insecurities about his abilities, the cry for Help! -- but offers quite revealing personal insights: he and wife Cynthia lived in a London apartment upstairs that of Beatle photographer Bob Freeman and his wife Sonny, with whom Lennon began a casual affair. The Freemans’ apartment was decorated in stylish Scandinavian furniture and Lennon later wrote about the affair: “she showed me her room, isn’t it good, Norwegian wood.”

Neither Bob nor Cynthia got it.

The book is full of such detail, and Lennon’s generosity is given equal place with his parsimony, his toughness countered by some genuine soft spots. As a boy he brought home a stray kitten and Aunt Mimi said that for the next 17 years, wherever he was in the world, he would always ask after it. In the Dakota where he lived in the last years of his life there were half a dozen cats which he adored.

The reappearance of his father -- whom Lennon supported financially -- makes for very interesting reading and they appear to have been well reconciled, as he was later with Cynthia. And briefly with Paul McCartney.

The arrival of Ono into his life undeniably freed him from the constraints of being a Beatle and with money, passion and a profile he grabbed headlines again: but when she was racially insulted and he publicly ridiculed his energy took the form of anger and in many ways he reverted to the bitter, sharp-tongued teenager he once was.

In the studio recording what became Let It Be he and an increasingly frustrated George Harrison -- who was captured in the film in a verbal confrontation with McCartney -- came to blows.

“You’d think it would have been with Paul, but it was with John.” says Sir George Martin. “It was all hushed up afterwards.”

When he and Ono separated for the famous Lost Weekend in LA getting boozed and obnoxious with the likes of Ringo, Harry Nilsson and others which lasted over a year, he was accompanied by May Pang, one of Ono’s growing number of assistants. Her book of this period glosses over the callous and indifferent treatment Lennon meted out to her. It makes for uncomfortable reading here.

The account is also insightful in dealing with how malleable his politics and peacenik image actually were.

Ono, who assisted Norman in a series of candid interviews over three years and also opened doors to others for him (notably their son Sean and her daughter Kyoko), told the writer in late 2007 that she was upset with the book and wouldn’t endorse it.

“Her reasons were various but the principal one was that I had been ‘mean to John’,” writes Norman in his acknowledgements.

Certainly the book fearlessly confronts Lennon’s shortcomings, which Ono herself acknowledges in more gentle and general terms these days. Speaking about his art recently she said, “there’s an incredible power in these pictures. John was very truthful in a lot of his art. He wanted people to know him not as some kind of angelic, perfect person, but as someone whop was trying very hard to be good, not always succeeding but always showing his human side.”

Recently I spoke with her about Lennon’s art and another touring exhibition, but also asked her -- given the candour of that statement -- just what her objections to the book were.

“I thought some parts were out of context about John,” she said, “and they weren’t fair to John. But I am shutting up about this because one of the reasons that was played up as ‘Yoko does not like this’ is because it was just a selling point.

“But I bless it,” she said half-heartedly.

Perhaps of more interest than her comments -- she is ruthlessly protective of Lennon’s image -- could come from their son Sean who gets an insightful chapter of his own reflecting on the father he never really knew.

He comes across as balanced and offers a mature assessment of the man who was only there for the first five years of his life. And sensibly for the sake of his own sanity and musical career, he puts some distance between himself and Lennon’s fans.

“My mom doesn’t really understand why I don’t want to meet those who worship John Lennon,“ he says, “why I don’t want to go to the Lennon tribute concerts or visit the John Lennon Museum.

“It just hurts too much. I’ve sung This Boy at a tribute concert because I love the song and I’m a professional musician. I can do any gig I’m asked to, but I didn’t like doing it.

“It’s not that I don’t want to honour him, because I feel like my whole life is a living tribute to him. But to go to a museum or see a movie that depicts his life, it just hurts.

“Watching a show about him on Broadway for me was like going naked through the flames of Hell because those memories I have of my childhood are so important to me. To see them co-opted to make a diorama in a museum or a Broadway show makes me feel like I’m being violated.”

That Sean Lennon should speak with such candour -- and perhaps mirroring the sentiments of those who have been uncomfortable about Lennon's artistic expression manipulated for commercial ends -- is a measure of the trust many put in Norman to tell the truth about the many facets of John Lennon. And you feel he has.

Lennon‘s voice, much quoted in life, also comes through frequently in these pages, no more clearly than in the final interviews in New York when he was voraciously collecting the detritus of his Liverpool childhood and had achieved a measure of contentment, if not happiness.

“I’ve never claimed divinity,” he told one interviewer. “I’ve never claimed purity of the soul. I’ve never claimed I have the answer to life. I can only put out songs and answer questions as honestly as I can, but only as honestly as I can, no more, no less.”

At the end of troubled, rewarding, complicated and rare life, that seemed a fair and modest statement of acceptance and fact.

There is an interview about this book here.

Angus BAxter - Apr 19, 2010

I think this is a great book. So well-written and entertaining reading. The author is obviously a fan, but in spite of this, it gives a relatively balanced view of Lennon's life.

SaveInteresting to compare this book with another I have read recently. Tony Bramwell's auto biography. A man who was there in the Beatles inner circle throughout the 60s. He has a good sense of perspective and sense of humour. Yoko gets an absolute character assasination. But there again, Tony is best mates with Paul, so perhaps it just goes to show that history is not presenting the facts, just a point of view.

post a comment