Graham Reid | | 2 min read

If we believe that, as is commonly said, great art is born of great suffering then Norwegian painter Edvard Munch (1863-1944) was born to make great art. He certainly exceeded his quota of great suffering.

Munch's mother died of tuberculosis when he was 5 and his sister Sophie - the subject of his first major work, The Sick Child - succumbed to the same disease nine years later. His father died in 1889 and Munch himself was frequently ill, suffered from nervous disorders and exhaustion, had a breakdown, drank excessively, engaged in dramatic and disappointing love affairs, lost two finger joints on his left hand as a result of a gunshot wound sustained in a duel ...

That he lived to his 80th birthday, the last decade suffering partial blindness, must have been as much a surprise to him as it was to the art world and his diminishing circle of friends and colleagues.

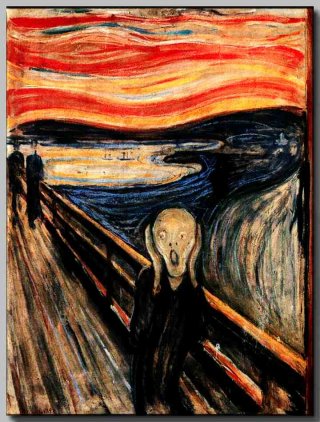

Great suffering, for sure, but also great art. His vivid, metaphorical works, such as The Dance of Life at the close of the 19th century, captured an emotionally dislocating sense of inner turmoil, and the fearful darkness encountered when there's the realisation of the uncertainty of life and the eternal presence of death.

Munch rode the boundary between Impressionism and Expressionism - he was influenced by Cezanne and Degas - and in turn influenced artists such as Ernst Kirchner in the early part of this century and more recently American painter Susan Rothberg, whose Half and Half of 87 is, as critic Robert Hughes observes, a resigned cousin to Munch's most famous work, The Scream.

The Scream has become an artistically diminished icon and is now part of the

detritus of popular culture. The emotional resonance of Munch's terrifying

vision of anxiety has been reduced by its reproduction on tea towels, posters

and postcards, cartoons, fridge-magnets and, of course, by that plastic

inflatable which stands in the corner of student flats and hip post-modern

houses all across the Western world.

Confronted by the fridge magnet or blow-up doll, it takes a great work of mind to recontextualise this work as a powerful visual symbol of inarticulate fear. Munch's own words - he was a prolific writer - serve to remind of his vision: "While I was out walking, the sun began to set. Suddenly the sky fumed blood-red. Tongues of fire burned above the blue-black water. I stood trembling with fear. At that moment, I felt an endless scream passing through nature."

It's as if Wordsworth had read too much Edgar Allen Poe before walking in the Lake District at night.

Norwegian novelist, composer and ECM pianist Bjornstad has reconstructed Munch's remarkable life from the artist's letters, literary jottings and memoirs, plus the considerable accounts by friends and contemporaries.

As with Munch's work, it is demanding.

As with Munch's work, it is demanding.

It is a fictional biography written in short, often poetic and impressionistic passages, through shifting perspectives, from representation of the artist's inner turmoil to reconstructed conversations and accounts of historical events which influenced this singular painter, etcher, lithographer and wood engraver.

These 380 pages - not illustrated, so have a primer to Munch's work on hand - which dive deep into the human condition, can be unsparingly bleak and harrowing.

In Munch's work and through this inventive account we can feel the darkness at the break of noon, as Bob Dylan once wrote.

post a comment