Graham Reid | | 3 min read

Tom Waits: What's He Building?

One of Tom Waits’ most eerie yet surprisingly popular songs is the speculative What’s He Building? from his 1999 album Mule Variations. In it neighbours wonder about the odd nocturnal activities of their neighbour: "He has no friends and his lawn dying ... enough formaldehyde to choke a horse, what's he building in there?" They -- and by extension the listener -- wonder on what dark deeds might be going on.

Tellingly, Waits -- for almost three decades since his marriage to Kathleen Brennan in ‘80 and shut off from the media he once courted -- sees it another way: that it is about people’s intrusiveness and the presumption they have the right to know all about their neighbours.

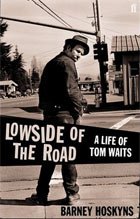

This is a perspective Waits biographer Barney Hoskyns will recognise: neither Waits nor Brennan, his musical collaborator, would co-operate with him. And that cone of silence spread like an epidemic.

Hoskyns found many musicians, fellow travellers and Waits friend (Keith Richards, filmmaker Jim Jarmusch and others) checked with Waits and Brennan if it was okay to talk, and most came back with a polite, “Thanks but no thanks“.

Hoskyns -- a reputable rock writer and critic, who interviewed Waits twice in person and on the phone a few times long before this unauthorised biography was mooted -- was not only up against the shut-out, but his own questions about how such a book could be written in the absence of its subject.

His lengthy prologue considers these doubts, the problem of imposing autobiographical meaning on Waits’ lyrics, and how to deal with a man who created his own persona in the late 70s.

That said, there were a substantial number of early interviews with Waits for Hoskyns to draw from -- the 2005 collection Innocent When You Dream among them -- but even here was a problem: Waits was notorious for self-invention and shaggy-dog anecdotes.

Indeed what is clear is that Waits is a remarkable piece of self-invention: the son of divorced, middle-class school teachers (his father an alcoholic, a trait which Waits inherited), he was a voracious reader -- the Beats, Burroughs, Bukowski -- with a passion for the music of his parents generation.

In the post-hippie climate of California in the early 70s when the Eagles and singer-songwriters like Jackson Brown and other Laurel Canyon cowboys were taking off, Waits emerged as a blearly lounge singer who not only had little in common with the musicians of his day but openly despised most of them.

Waits invented himself as Beat barfly, living in self-imposed squalor in the rundown Tropicana Motel which became an alternative performance space where he acted out this new life -- but increasingly the image became the man. “I really became a character in my own story,” he admitted later. There was a long period in which Waits seemed unable to escape the role of Tom Waits.

“I’m tired of being referred to as Wino Man. It was okay for a while, but I’d like to a little more three-dimensional.”

He sought father figures in older men -- record producers, Bukowski and others -- but it was Brennan, to whom he became engaged within a week of their meeting, who rescued him from himself and the image.

He broke with longtime friends such as producer Bones Howe whom he wouldn’t see for a decade (“I don‘t blame Tom, I blame Kathleen,” he told Hoskyns. “She really separated him from everybody.”

Brennan steered him towards the artistic community in New York, his music became more inventive and complex, and they started a family.

The one-time boozy misfit noted, “Family’s real important, you know. If you don’t have one you invent one. Even Hell’s Angels have a sense of family.”

Hoskyns manages to piece together the threads and events of Waits’ early life -- yes, he finds biography in the lyrics -- but once Waits disappears into a private world the story becomes more problematic.

Interpolated in the text are Hoskyns’ encounters with those who have been willing to speak and some in depth concert reviews, but they smack a little of desperation and padding.

But by the last half Hoskyns is down to analysis of each album track, some linking segments, and includes an almost defeated essay-type piece about critical opinion on Waits‘s music: Waits won’t be surprised to learn most respect his difficult work but actually prefer his barfly ballads.

The book ends with the author at the stage door of a Waits concert in Edinburgh last year. He is standing in the rain by a black tour bus -- waiting for the man, as it were -- only to realise Waits has been in the other one beside him all along which pulls out into the night.

Hoskyns is smart enough to see the metaphor.

This book may be what Hosykns’ publisher calls “the definitive biography of a notoriously private performer” but the author was still wise to subtitle this with the indefinite article.

There will be no definitive life of Tom Waits -- who turns 60 in December -- unless Tom writes it or co-operates. And that’s unlikely.

These days Tom Waits has a very private wife, life and children -- and he’s probably building something in there.

For more on Tom Waits at Elsewhere including album reviews, a recent career overview and a look at the collected interviews by Mac Montandon go here.

Peggy in America - Feb 5, 2019

It's funny, what recipients will attach themselves to: what they want to hear. I fin Mr. Waits a deeply spiritual man, with metaphors deep, but they only come out in, from, by, and through, what ya hear. It's the best dichotomy there is. I'd imagine he knows that, but has no "use" for it.

Savepost a comment