Graham Reid | | 5 min read

Notes from the Underground: Why Did You Put Me On (1968)

Somewhere among my old photographs at home is one of me standing beside John Lennon’s psychedelic Rolls Royce. It was London in late ‘69 and -- aside from revealing the embarrassing affectation of a black cape -- it‘s most interesting for what is in the background: a Morris Minor of the kind that was considerably more common than Rollers painted like gypsy caravans.

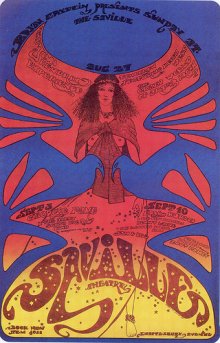

It all seems so long ago: hippies at Haight-Ashbury; the Beatles Sgt Pepper’s; A Whiter Shade of Pale; multi-coloured clothes from Granny Takes A Trip; designers like The Fool and posters by Hapshash and the Coloured Coat . . .

All this colour unleashed into a world of mundane Morris Minors?

“A benevolent virus had descended and happened to hit San Francisco and was spreading out,” said San Francisco poster artist Victor Moscoso. “Pretty soon everyone was going to live by the Golden Rule and treat everybody the way they wanted to be treated.”

Yes, it does seem so long ago when faced with that naivety.

But the psychedelic hippie era was a time to acclaim all things bright and beautiful.

But the psychedelic hippie era was a time to acclaim all things bright and beautiful.

“Our concept,” adds British poster artist Nigel Waymouth -- who with Michael English went under that exotic Hapshash name -- “was to plaster the streets of London with this very brightly coloured and beautiful poster work at a time when most posters in the street were rather drab and wordy.”

Not to mention the drabness of London streets behind me and the Morrie.

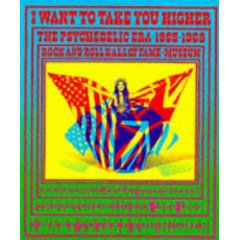

Waymouth is just one of the many artists, musicians and would-be social reformers interviewed for I Want To Take You Higher, a fat, fascinating and yes, very colourful book initially published in ‘99 to coincide with a Rock and Roll Hall of Fame celebration of the Psychedelic Era 1965-69.

With an informed overview essay on both American and British psychedelia woven between pictures of love-ins and be-ins, rock bands and stoned tribal gatherings, I Want to Take You Higher seduces the eyes and consciousness back to a time when there was an appreciable social cultural shift -- and when to be young was bliss.

And to be young in London and San Francisco was very blissy indeed.

And some were very young: George Harrison, who had been through Hamburg, Liverpool and Beatlemania before Sgt Pepper’s was still only 24. Grace Slick of Jefferson Airplane was only 23 when the Summer of Love started.

I Want To Take You Higher is also shot through with humour: the guitarist from Quicksilver Messenger Service, Gary Duncan, recalls them being high and playing for two hours at a stretch simply because “endings and beginnings were real hard, so we’d just keep going until things fell apart”.

Through retina-challenging posters and shots of the famous (see Jimi tease out his hair, be amused by yellow striped jackets) to stoned optimism, these were also the Out of Focus Years, literally and metaphorically.

Through retina-challenging posters and shots of the famous (see Jimi tease out his hair, be amused by yellow striped jackets) to stoned optimism, these were also the Out of Focus Years, literally and metaphorically.

And whatever happened to the idea of multi-coloured, psychedelic bread as pictured?

They were intellectually volatile years however: in London the nascent hippie movement was driven by intellectuals such as gallery owners Barry Miles and John Dunbar. In the United States it was driven by the link back to the Beat Generation which had earlier been forged by poet Allen Ginsberg’s friendship with Bob Dylan. Jefferson Airplane’s Jorma Kaukonen was a sociology graduate.

Inevitable people looked beyond the parameters of their world: artists to music then to politics to Vietnam to protest.

And there were enormous social changes: Martin Luther King and the civil rights movement, and Muhammad Ali sentenced to five years for refusing to serve in the US army.

The book notes these things too.

They were colourful years -- but you note that many women on the edge of the frame are still in Jackie Kennedy suits, and you suspect that somewhere just out of shot is a Morris Minor.

In the introduction editor James Henke concludes by saying, “It was a time when anything seemed possible. People thought they could change the world -- and they did.”

Well, maybe and maybe not.

Richard Nixon was there too. Soon enough so was Charlie Manson.

Maybe things also reverted to type? Paul McCartney who earned the ire of the Establishment for his pro-LSD pronouncement is now a knight of the realm, as is Mick Jagger who used to be found at the right hand of the Devil.

What “the psychedelic years” did do however was alert the Western world to the idea that there were more options and lifestyles available -- and, with the growth of rock music, more business opportunities and ways to rip people off. Woodstock wasn’t put together by philanthropists.

What “the psychedelic years” did do however was alert the Western world to the idea that there were more options and lifestyles available -- and, with the growth of rock music, more business opportunities and ways to rip people off. Woodstock wasn’t put together by philanthropists.

As a result of these years in which people and ideas were freed up came the Green movement, direct action protest, the gay and women’s movements, the Weathermen and Yippies, revolutionary movements like the Red Brigade . . .

Hmmm.

But we now take for granted we live in a world of individual choice.

When a credit card company announced in the late Nineties that Jerry Garcia would have his art commemorated on a card you had to conclude “what a long strange trip it’s been”.

For the soundtrack to this era try Love is the Song We Sing: San Francisco Nuggets 1965-70.

post a comment