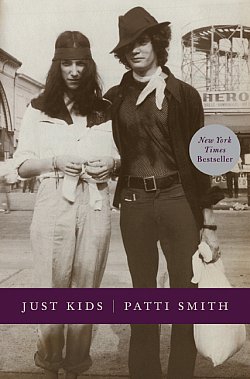

Graham Reid | | 4 min read

In 2004 when Patti Smith released yet another predictable album, the critic Ian Penman correctly observed, "It sounds like she hasn't heard a single thing outside her own music for about 25 years".

Smith, acclaimed for her marriage of rock’n’roll and poetry in the late 70s, has been in a creative whirlpool the past four decades and her constant referencing of her heroes and mentors -- William Burroughs, the photographer Robert Mapplethorpe, Jean Genet, Bob Dylan, Arthur Rimbaud - became increasingly tedious.

The recent documentary Dream of Life repeated the wearily familiar refrain of names and places (the Chelsea Hotel, CBGB’s club in New York) as she got herself together following the death of her husband Fred “Sonic” Smith.

So it is little surprise that this book, an autobiographical insight into her early life and years with Mapplethorpe in New York before she found rock’n’roll fame should also dance around the same territory.

But here is the revelation for those weary of her self-mythologising and tiresome choruses: she writes about this formative time with bone-bare honesty, an eye for detail and with a poetic lilt that is utterly engrossing.

When her friend, saviour, lover and soul companion Mapplethorpe was dying in in ’89 he asked her to promise she would write their story. And even if “Robert” and “Patti” had never become who they did, theirs would still have been an astonishing beautiful, sensitive and sad account of a rare love and trust between a man and woman drawn to each other by a spider web of fate and affection, but fated to be pushed apart.

As a skinny and sensitive suburban child Smith decided she would be “an artist” although concedes that, despite a voracious reader of lives of artists, she had no real idea what that meant.

She left her New Jersey home and threw herself into New York where she was homeless although uncharacteristically lucky in her chance meetings with people who cared for this almost genderless waif.

One was Mapplethorpe, also an aspiring artist but clearly more ambitious and singular in his purpose. Smith unflinching paints him as envious of the success of others.

They become immediate soul-mates and companions and even as he slowly discovered his homosexuality they remain close partners.

Theirs is a life of privation, illness and hunger -- but art sustains them.

Smith’s New York is alive with the spirits of those she has read about and she writes with sharp emotional and physical detail.

In 67 on the day the jazz saxophonist John Coltrane is being buried she passed his funeral: “Later I walked down Second Avenue, Frank O’Hara territory. Pink light washed over rows of boarded buildings. New York light, the light of abstract expressionists. I though Frank would have loved the colour of the fading day. Had he lived, he might have written an elegy for John Coltrane like he did for Billie Holiday.”

Smith admits to great naivety -- she knew little of homosexuality, did no drugs until she was 23, was almost childlike in her trust of strangers -- but was also inspired by seeing Jim Morrison of the Doors in performance.

Guiltily she felt she could also be a performer (“I felt both kinship and contempt for him”) although it would be many years before she started setting her poetry to music.

Before then were the grim days with Mapplethorpe as their love was tested by him picking up tricks for money, their coldwater living spaces, the better times at the Chelsea Hotel where there was a spirit of camaraderie, and the encounters with Jimi Hendrix, Janis Joplin, playwright Sam Shepard and others.

There is also humour as in her first meeting with the poet Allen Ginsberg in a laundromat where she doesn’t have enough money. He offers to help then after a discussion about Walt Whitman asks if she is a girl.

“Is that a problem?”

Ginsberg laughs: “I’m sorry, I took you for a very pretty boy.”

Smith tells all of this without self-aggrandising, emphasising her innocence, aware of the privilege they enjoyed even as struggling artists (“no one in the back room [of Max’s Kansas City club] was slated to die in Vietnam, although few would survive the cruel plagues of a generation”) and of a deep bond that remained even as she and Mapplethorpe went their separate ways.

“You got famous before me”, he said when her single Because the Night written with Bruce Springsteen made the top 20 in 79.

But he was also proud of her, as was she of him when his brutally honest and often controversial photographs became the talk, and scandal, of the art world.

But this is not the story of their subsequent fame. It is of two young people, just kids, making their way in a world that was at first indifferent and then increasingly open to whatever developing talent they had.

It is, like Bob Dylan’s Chronicles, a rare book by a rock musician in that it rings with poetry and close observation, personalises what has become mythologised over time, and speaks directly from a heart that has been battered but never -- despite the losses -- been broken entirely.

Just Kids -- while revisiting the world which she inhabited and has spoken about to the point of tedium -- is an eloquent testament to the power of belief in art and pure love.

post a comment