Graham Reid | | 7 min read

To put it

bluntly, Sarah Whitelam didn't muck around. The day after John Nicol

sailed off for Britain – the man with whom she'd had child and

promised to remain true to in the days before his departure – she

recovered from her disappointment and married the convict John Walsh.

These

were very different times – the colony of Sydney in 1790, just two

years after the First Fleet arrived – and Sarah, a convict

transported for seven years for stealing lengths of material from a

Lincolnshire shop, was simply being practical.

People

were forced to make whatever living arrangements they could. There

was much intercourse – often sexual – between the thousand or so

inhabitants of this remote outpost, and lines of class or position so

pronounced in Britain were obliterated by human need and their

situation.

And they

were a mixed bunch, not simply woebegone petty thieves or murderous

thugs which Britain had cast to the far end of the world.

D'Arcy

Wentworth, for example, was a highwayman-cum-surgeon not yet 30 and

had come from a decent family in Ireland. He had become something of

a cause celebre

and his trial for robbery was attended by members of the royal

family.

This

dashing rogue – later a partner in the building of Rum Hospital in

Sydney, the superintendent of police and a president of the Bank of

New South Wales – arrived in the colony alongside political

dissenters, criminals, the highly literate and dirt poor Irish

peasants whose sense of geography was so ill-informed they thought if

they escaped over the hills they would be in China and could start

life anew.

These are

the characters – Aboriginals and other explorers also – who

populate Thomas Keneally's ambitious history Australians:

Origins to Eureka (reviewed here), the

first volume of an intended trilogy tracing the development of the

country from pre-history to the present.

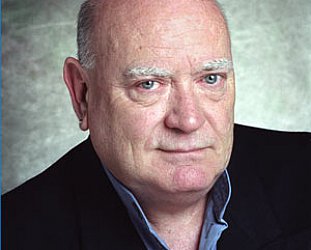

Keneally's

title is instructive. His is a story of people and in these 600 pages

they breathe and sweat, fight and fiddle the books, are heroic and

hateful. We see them at their best and worst. And, 74-year old

Keneally hopes, in an honest portrayal.

This

personable author unashamed of a casual profanity laughs about the

history texts he endured as a schoolboy (“back before the pyramids

were built”) in which “the early governors were ponces in wigs

and dressed in uniforms we'd never seen anywhere”.

“We

didn't have a sense of them as people at all, of [first Governor

Arthur] Phillip sitting by his fire with his housekeeper – whom he

was 'on' – and feeding his pet possum a grain of rice at a time.

“But he

was probably in his shirtsleeves and thinking, 'My God, if those

problems with France develop [the British government] are going to

forget us and these people here are going to be eating each other'.

“You

know, Phillip was an Enlightenment man enchanted by the Aboriginals –

and was light years more advanced in his thinking than John Howard

ever was.

“The

idea of all that is more interesting than this bloke in a strange

uniform.”

In the

early 60s when he began writing, Keneally (“it's Tom”) promised

himself he would try to write a book every year to 18 months, and

he's been largely on target. He has written dozens of novels (“In

fiction you try to get to the truth by telling lies”) including The

Chant of Jimmie Blacksmith

which was shortlisted for the Man Booker Prize in 1972 and

Schindler's Ark

(adapted for the film Schindler's

List by Steven Spielberg,

and which won the Man Booker in 82).

He has

also written plays and almost two dozen works of non-fiction, notably

histories of Australia including The

Great Shame and A

Commonwealth of Thieves, The Improbable Birth of Australia

in 2005, material from which is assimilated into Australians:

Origins to Eureka.

Of

Irish-Catholic ancestry, Keneally is founding chairman of the

Australian Republican Movement, one of his country's Living

Treasures, a passionate rugby league follower (Manly Sea Eagles) and

laughs about his work methods which he says lack discipline.

Unlike

many authors, he sets himself no daily word-count goal, and the only

ritual he observes is provided by the laptop: “It starts humming

and that causes the brai to secrete chemicals which say, 'Pull your

thumb out and get a move on'.”

Although

he has written about American and Irish history, it is that of his

own country which he finds endlessly fascinating and tries to

humanise, to get its founders “off the plinth and into their shirt

sleeves”.

He takes

great amusement in speaking of Sir Henry Parkes (1815-96), the

“Father of Federation”, who was perpetually in debt and promoted

people to the Legislative Assembly who would lend him money.

“That

was his lifetime weakness. At 80 he was still being harried from

house to house and although a consumate politician he who couldn't

manage his domestic affairs. Once you know that he's no longer a

ponce on a plinth.”

If the

cast of Australians

is colourful, the rapid pace of the country's development is due to

this crucible of political dissenters which Britain had exported,

many of whom had a history of social awareness and a desire for

political justice.

“Very

early on you had people who saw themselves as political prisoners and

better than those who jailed them.

Australians

also shows how political developments in Britain and the

revolutionary spirit in France and the United States impacted on the

fledgling colony. Far from being remote and removed, with every new

arrival came political ideologies.

“Most

societies begin with Eden and go from there, America begins with the

redeemed arriving at Plymouth Rock, people too good for Britain,”

he laughs. “And its all upward and onwards.

“But we

began at the bottom. Ours were selected not by God for a garden, but

by what they called 'the best judges in Britain'.”

Yet with

two decades this “criminal kingdom” was peopled by those who, as

historian Alexander Harris wrote “are growing up a race by

themselves; the fellowship of country has already begun to

distinguish them and bind them together in a very remarkable manner.

Whenever they come in contact with each other, even when considerable

differ of rank exists, this sympathy operates strongly”.

“One of

the reasons [Australia] worked was the leavening of stroppy bastards

who resisted in all manner of ways and the reason is that the dream

of remote places, of more equitable places, attracts radicals.

Parkes, who was a Chartist when he was young, emigrates in part

because of this inherent promise in the place.”

This

first volume takes the history to the strike at the goldfields of

Eureka in 1960, the second volume on which Keneally is currently

working will end with the fall of Singapore in 1942, both pivotal

events which changed the way Australians perceived themselves and

their position in the world.

“I took

this to 1860 because that's the beginning of representative

government. Both our countries produced extraordinary institutions

for their time even though they weren't perfect democracies in the

absolute Hellenic sense of the word.

“Even

though they appointed upper houses with rich old bastards who sat on

legislation, the institutions for their times were revolutionary and

were largely in place by 1860. “The fall of Singapore changed the

geopolitics of the world. We'd spent our entire history up till then

wishing Asia wasn't there . . . when [Singapore fell] a whole new set

of priorities and realities hit us.”

Keneally

says what fascinates him as a historian – and he acknowledges

academics “not infected by literary theory” who have done social

and historical research – is that because Australia and New Zealand

are relieved of emperors, great captains and kings, “we are able to

concentrate on humbler history, but history which nonetheless shows

the contours of development of liberal democracies”.

“We are

often benighted people but you've got these extraordinary experiments

in liberal democracy in the 19th

century and whose traditions – despite the best intentions of

bureaucrats and politicians – have not deserted us yet.

“Our

history is rich in social issues and in the question of the

transplantation of culture and ideas, and how obscure people

blessedly kept an indicative journal of a major contours of our

development.

“It

sounds dull, but when you descend into the journals you see the daily

squalor and endeavor and ambiguity in 19th

century New Zealand or Australia.”

And in

Australians

the people's voices come through as the long, often brutal, arc of

history unfurls.

“Australia

never stopped being a convict settlement,” laughs Keneally. “The

Brits have this habit of sending their economic, social or academic

failures to Australia.

“So you

blokes in New Zealand think we're rough trade, but it's incredible we

can even use a knife and fork.”

post a comment