Graham Reid | | 3 min read

Tommy Steele: Rock with the Caveman (1956)

There is a widely held view, especially amongst those who came of age in the Sixties, that nothing much happened in British music before the Beatles.

Yes, there was Cliff Richard and the Shadows, and a few names like Marty Wilde and Billy Fury, and of course the Lonnie Donegan skiffle phase which lead into Tommy Steele . . . but really that was about it.

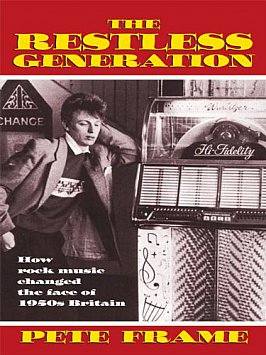

Rock writer Frame -- well known for his elaborate family tree schematics of bands and eras -- gives the lie to that view to some extent in this exhaustive overview subtitled "How rock music changed the face of 1950s Britain".

By going back to the post-war period and spotting in the history of the jazz passions of Ken Colyer, Chris Barber and others -- and their slightly straight but sometimes night-owl lifestyles -- he lays the ground for all that followed: how trad jazz morphed into a love of the blues, then how skiffle came along and eventually how Tommy Steele became a proto-rock'n'roll star with one eye on the "all round family entertainer" market.

There is much plain-speaking here: Bill Colyer (Ken's brother) dismisses Barber with "he's got an accountant's mind" and says their music wasn't jazz, just "Mickey Mouse Clinic music".

"The Barbers and the Donegans rewrite jazz history: to me they're still tiny-minded shit heads."

Those kinds of -isms and schisms between purists, progressives, letter writers to music magazines and fellow travelllers makes for an amusing view of just how small and petty this world was.

It is those who got up a head of steam and wrote to the likes of NME and Melody Maker who provide the most fun. Here is a record shop owner and jazz fan sounding off about the skiffle kids taking over jazz clubs . . .

"The utterly stupid antics of fans and fannies, who cavort and prance like inmates of a mental home during the recitals of music far beyond their comprehension" and noting later skiffle is "a problem of youth which must be solved in order to keep the true name and spirit of jazz clean".

The irony is of course that this "true jazz" was faux-Dixie played by musicians who had rarely met a black musician let alone been to America. The notable exception was the courageously itinerant Ken Colyer who headed off to New Orleans, played with black musicians (and was thrown in jail for doing so) and return ablaze with the spirit.

But mostly Britain carried on as usual -- the -isms and schisms in the jazz world -- until Lonnie Donegan took skiffle to new heights with the improbable hit Rock Island Line.

"Imagine a songwriter walking into any of the publishing firms on Denmark Street," he said later, "and saying, 'Look, I've written this song and I think it could be a hit. It's about a train driver in the States who fools the tax inspector, the revenue man, by telling him that his freight train contains only live animals which are not subject to a levy.

"The dumb-cluck takes his word for it, too stupid to notice that there's no sign of animal life, and let's him through without paying. Exhilarated the engineer speeds off down the track'. What publisher is going to to fall for that?"

Well, a whole nation did and Donegan became a star, further dividing the jazz and folk worlds. He went tot the States and had enormous success there also.

Frame's story is full of telling and often funny anecdotes, he reminds how insular Britain was (the Musicians Union wouldn't let Chet Baker play his trumpet but he was allowed to sing), and it is peppered with real characters like Ramblin' Jack Elliot, Leftist and graffiti pioneer John Hasted, roues like Lionel Bart who couldn't read or write music but penned Oliver! and dozens of hits, and of course Tommy Steele who (under the watchful eye of impresario Larry Parnes but more notably his inventive manager, former New Zealander John Kennedy) managed to become a star of records, stage and film.

And then there was Cliff Richard whose Move It was a breakthrough recording.

When it was played in a blindfold test to various indiustry people they said it was great -- but British studios could never get a sound that good.

With digressions into long forgotten pop movies and the tragic stories of could-have-been stars, this is a fascinating book -- but too often, especially when it comes into the world Frame remembers, the author's voice comes through with annoying and stupid interjections.

Yes, some of the soongs were naff and those pronouncing the end of rock'n'roll were naive and stupid, but Frame always feels the need to remind us of this in his own words.

There are a few mistakes -- Jimmy Nicol didn't come to New Zealand later with the Beatles -- but the accumulation of detail and voices is impressive. The real pity is that there are no photographs, not one to let us see these artists and this era which Frame loves so much.

And the Beatles? They only appear on the penultimate page. The world of British popular music changed again. And skiffle went the way of all flesh.

Nathan Boo - Apr 17, 2019

I love Lonnie Donegan and I'm only in my fifties(!) and grew up with My Old Man's a Dustman. I have a CD from 1999 - Lonnie Donegan, Van Morrison and Chris Barber live in Belfast. It's great if you like skiffle.

Savepost a comment