Graham Reid | | 2 min read

In one of those excellent but buried television programmes, various photographers who were in the Vietnam killing zones told of the stories behind some of those images imprinted on the collective memory of a generation.

That shot of the young girl running down the road, her back on fire from napalm? It was initially rejected because it showed frontal nudity.

The policeman in Saigon blowing apart the head of a suspected Vietcong terrorist? A South Vietnamese working for the Americans was there but failed to report it. That guy always did things like, he explained later, so he didn’t think it worth mentioning.

And Don McCullin, one of whose shots showed a wide-eyed and terrified American soldier staring fixedly ahead said he snapped off a dozen shots and never once did the GI blink or move, he was so numbed by the world he was witness to.

Photographers in war zones are witnesses too - albeit selective ones - and McCullin’s camera has been silent testimony to the horrors the last half of the 20th century wrought upon itself. He was in Cyprus and the Congo, Vietnam and Biafra, Bangladesh and the killing fields of Cambodia.

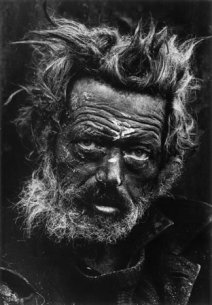

He pointed his camera into the faces of gangland London in the Fifties and the Kurdish peoples of north Iraq in 1991 when Saddam Hussein’s military thugs were gassing and bombing them.

His work, gritty black and white but sometimes unnervingly soft-edged given its grim subject matter, captures the essential humanness of conflicts.

Some eyes stare past the lens. Others,

such as Palestinian women fleeing East Beirut, glance momentarily

into the camera and our lives.

McCullin notes in a few words in this 200-page selection of a lifetime’s work that after Vietnam and while in Biafra in 1967 he lost interest in soldiers and strove to show the effects of war.

In page after engrossing page moments such as those of women mourning dead husbands, be they in Cyprus or Palestine, are captured in the midst of their tragedy. As with that photograph of sudden death in Saigon and the anecdote appended to it, it’s the casual universal inhumanity which gives the instant resonance.

Today McCullin lives in Somerset, his

negatives filed away as he tries to “eradicate the past.” The

human tragedy is slightly ameliorated by late works of penetrating

still lifes and dark pastorals akin to monochromatic Constables.

He says the struggles today are in the darkroom where he tries to resist the temptation of printing his recent pictures too dark.

Whether his photographs are engaging the faces of the homeless in Britain - children in Bradford three in a bed beneath damp, peeling wallpaper - or of a young Cambodian woman fanning her husband who lies legless on a makeshift hospital bed, they are all about the same thing -- the human condition and the inhumanity that creates it.

post a comment