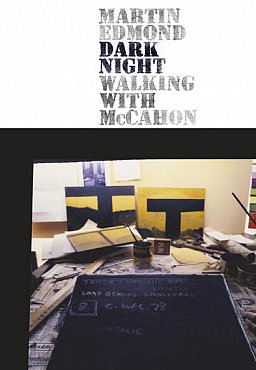

Graham Reid | | 2 min read

When Colin McCahon went to Sydney in 1984 to attend an exhibition of his work the attritions of alcoholism and that intensely personal religiosity he explored had taken their toll. He had given up any meaningful painting two years previous and was just three year short of death at age 67.

In a bizarre but telling incident, he went into a toilet block in the Botanic Gardens and seemingly exited out a different door. He went missing for 28 hours and was discovered in Centennial Park some distance away. He could say nothing of where he had been and was disoriented.

Expat writer and sometime Sydney cab driver Edmond, on learning of this in recent years, realised he too had been in Sydney at that time and that got him thinking. The McCahon incident has sparked this multilayered, insightful and most readable book in which the painter's lost hours are used at the prism through which Edmond refracts aspects of his own encounters with the painter (most notably a painting he knew from childhood which opens the account and an unhappy personal incident) and the various worlds – artistic, personal, religious and not least the marketplace -- in which McCahon lived.

As an exploration of an artist's life and work it also reads like an adventure into that dark night of the title when Edmond -- cautiously and with a useful instinct for self-preservation among the homeless and drunks -- retraces what he thinks might have been McCahon's footsteps.

But this is just the hook to hang another more interesting conceit on: Edmond uses the Stations of the Cross – which McCahon had painted – as starting points for discrete essays within the book which are digressive encounters with the man, his work and his milieu, but which also weave through aspects of Edmonds own life, the characters he encounters in his “dark night” and evocative descriptions of Sydney then and now.

It is quite some book about McCahon which includes the Red Mole theatre troupe and drag queen entertainer Carmen alongside Veronica (who allegedly wiped the face of Jesus as he carried the Cross) and a passing mention of the pop group Boney M within a few pages, and can also look at the prices for McCahon paintings at auctions.

Edmond is most often clear-eyed (“McCahon's painting life followed the familiar romantic trajectory from struggle and penury relieved by a few faithful friends and believers through increasing fame to the megastar status his work possess in the art world today”) and doesn't resile from criticism of the painter's puritanism and guilt: “Yet his need to make art, which was both obsessive and compulsive, must have been driven at least partly by egotism, by the urge to be remembered forever”.

However Edmond also had the great good fortune in his experiment of walking in what might have been McCahon's footsteps that night to experience a vision. Some might cavil at that coincidence but he writes about it so poetically it soars off the pages.

Colin McCahon has been the subject of any number of texts and textual analysis, but Edmond liberates the artist from that world and presents him as the troubled man he often was. He speculates and puts himself int the frame at times, and despite the artifice of walking in that dark night of the lost soul, this is a remarkable book where fact and fiction, uncomfortable reality and visionary art exist in the same emotional, and often physical, space.

If you only ever read one book about the creative, troubled soul that was Colin McCahon . . .

post a comment