Graham Reid | | 2 min read

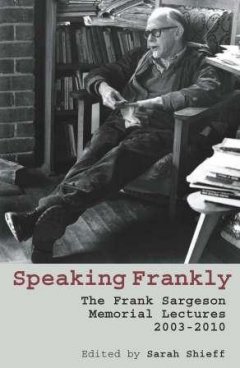

Get past the crushingly obvious title and the cheap looking cover, and inside this collection are eight provocative, interesting, idiosyncratic and insightful essays which speak not just of New Zealand's Frank Sargeson but in some instances of how we see ourselves and our writers.

You might also need to skip the introduction which begins with the uninviting, “ '23 March 1903, London Street Hamilton. To Edwin and Rachel Davey a son, Norris Frank'. If birth notices had been de rigueur in the small Waikato town, so might the conventional Davey family have advertised the arrival of their second son . . .”

But from Michael King's inaugural lecture in 2003 – in which he addresses the importance of Hamilton, where Sargeson spent his first 22 years, on the author's psyche and work – this is a beguiling and important collection of literary observations, telling reminiscences by those who knew the writer best, and thoughtful refractions of his work, life and friendships.

Lawrence Jones looks at the patchy work and legacy of the generation which was anointed by the writer and became billed as “the sons of Sargeson” while in search of the Great New Zealand Novel; and Kevin Ireland, Christine Cole Catley and Graeme Lay weave their own encounters with Sargeson into essays which are amusing, autobiographical, honest and almost photographic in their descriptions of encounters in Sargeson's small Fibrolite home on Esmonde Road in Takapuna.

Peter Wells – heavily quoting from or referencing other literary figures such as E.M. Forster, Gordon McLauchlan, John Ruskin, Walter Benjamin and others – takes an interestingly meditative approach to the fragility of our memories of place in relation to Sargeson's home which was barely saved from demolition, and Elizabeth Aitken Rose ponders how and why we preserve the homes of our writers, some of which (like Katherine Mansfield's birthplace) they barely inhabited.

Through memories, encounters and letters we see Sargeson in his many manifestations as a young man, struggling writer, mature mentor, patient friend to the seemingly impossible Janet Frame and as an old fellow aware of his frailty but still writing encouraging letters to the likes of Owen Marshall.

The generation which knew Sargeson intimately is aging – and passing, Sargeson and Frame's biographer King in 2004, Cole Catley in August – which makes these lectures even more resonant.

The final essay offers a way forward: Marshall – who occasionally corresponded with Sargeson but never met him – uses the author as a starting point for a discussion on the importance and resonances of being a “true reader” immersed in books, and how they enrich us. As Sargeson's did and still do.

Ireland observes in his typically

delightful, anecdotal and thoughtful talk, “Frank tells us

continually, in his tales, the truth about people and a world that he

perceived to be have been shattered by social disasters that

sometimes had seemingly trivial origins.

Ireland observes in his typically

delightful, anecdotal and thoughtful talk, “Frank tells us

continually, in his tales, the truth about people and a world that he

perceived to be have been shattered by social disasters that

sometimes had seemingly trivial origins.

"He made it one of his life's tasks to reassemble the fragments of these disasters in order to shape personal and universal meanings . . .

“Frank was a man who lived a complex inner life in outward simplicity. His mind was as subtle as any I have come across. He ran the best literary oasis in the desert.

"He was an entertainer and enchanter, as well as a great teacher and a source of strength.

“His frailties gave him a deep and subtle human sympathy and understanding . . . “

And that man, that writer and friend – flawed as all people are, no matter what their gifts – lives in all his complexity in these wonderful talks.

post a comment