Graham Reid | | 8 min read

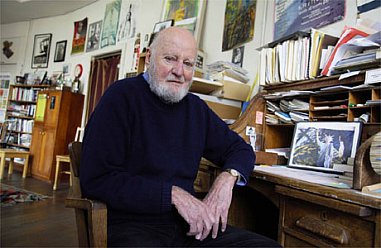

Lawrence Ferlinghetti sounds in feisty spirit. Indeed, my call to his famous City Lights bookshop in San Francisco finds the 81-year-old deeply irritated, if not to say downright angry.

It's all because of the recently released album of him reading selections from his poem, A Coney Island of the Mind, his 42-year-old poetic meditation which has been translated into nine languages.

No, he wasn't surprised when a record company approached him to do the reading, far from it. "It was long overdue. The book has been out since 1958 and sold a million copies. I'm very happy to get a CD out - even though I can't stand the music."

Ah yes, the backing by saxophonist Dana Colley from the Boston-based band Morphine - the cause of his ire. The low-range, broody music is fine of itself but Ferlinghetti doesn't like it. Hates it, in fact.

He recorded his part of Coney Island in the basement studio of Francis Ford Coppola's Sentinel Building in San Francisco -- the same room where Allen Ginsberg performed Howl for the first time in the mid-50s and where the Grateful Dead would later record -- "and then the tape was shipped to Boston where the musicians presumably listened to my poems and did their number."

He's never even spoken to Colley and says, "It's a helluva way to produce a record, to not have the musicians in the same room to play while the poet is reading. It's absurd to do it like canned music."

And the backing, he feels, simply wasn't the right choice for his work. "They call it noir-jazz and my poetry is very lyric, noir-jazz is not at all lyric. I objected heavily but my contract didn't give me any say and they went right ahead with the music I hated.

"I find that music is a complete bring-down of the poems. They went ahead with complete disregard of my wishes in the matter."

Artists are not necessarily their own best critics, however and, while a listener might concede occasional stylistic clashes, the CD offers some provocative, enjoyable listening. And, of all Ferlinghetti's work, Coney Island is, as critic Robert F. Kiernan wrote, "the most sweet-tempered of his books. The political and societal passions that tend to dominate his other volumes strike a harsher, less engaging note."

Colley provides the "In woods where many rivers run" section with an appropriately pastoral piano setting, and the innocent, pre-psychedelic vision of "the penny candy store beyond the El" sits above a wailing, slow-bop jazz saxophone. His most famous poem, Dog -- "the dog trots freely in the street and sees reality ... drunks in doorways and moons on trees" -- rides over a lovely loping rhythm.

But Ferlinghetti won't have it. It's been out a few months but he's still mad as hell.

Born in 1919 in New York, Ferlinghetti gained a degree from North Carolina, then an MA from Columbia University. He saw active service in Europe during the Second World War and was in the American army of occupation in Nagasaki only weeks after the atomic bomb was dropped.

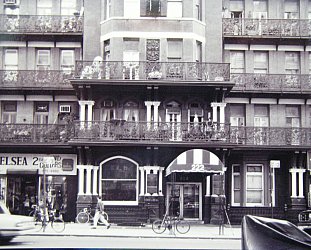

After the war he earned his doctorate in poetry at the Sorbonne in Paris, then in 1951 moved to San Francisco. With Peter Martin he published City Lights magazine (named after the Chaplin movie and its image of the perennial outsider) out of second-floor rooms on the corner of Broadway and Columbus Avenues.

In 1953 he opened the City Lights bookshop on the ground floor, which today is, as he says, "a literary centre and tourist destination. We still have a lot going on, 10 book signings this month. We're open seven days a week until midnight and there are always people here."

Yes, City Lights has been hit a little by the dot.com booksellers ("under 5 per cent. Ours is a special case") but what they stock is books. "No greetings cards, no calendars, just totally books," he laughs.

In contemporary American literature, Ferlinghetti -- dubbed Poet Laureate of San Francisco in 1998 -- is a seminal figure: a poet, novelist, translator, essayist and painter; and the most visible survivor of the Beat Generation of the 50s which included Allen Ginsberg, Jack Kerouac and William S. Burroughs.

In some quarters his reputation rests on his innovative series of Pocket Poet publications which he launched in 1953 with the intention of economically taking poetry to ordinary people.

His personal philosophy of the poet as acrobat is encapsulated in his lines "constantly risking absurdity and death when he performs above the heads of his audience."

It was the fourth book in the Pocket Press series, Ginsberg's Howl, which put his name in the faces of Americans. He was prosecuted for publishing an obscene document (but "beat the rap," to use the parlance of the times) and while Howl rightly became recognised as the revolutionary poem it was, the court case and media circus revealed Ferlinghetti as a sharp thinker with an astute grasp of social and political affairs.

Where Ginsberg's Howl and Kerouac's equally famous novel On the Road were composed of highly polished streams of words with an urgent, bebop jazz momentum, Ferlinghetti's poetry has often been more quiet, winsome and wry. And as with other Beats, it is often better heard than read.

Being of the Beat Generation -- whose members often effected the marriage of poetry and music -- Ferlinghetti has no objection to the principle of poetry with musical accompaniment. He recalls performances with poet Kenneth Rexroth in the 50s in a jazz club in San Francisco's North Beach which were recorded for the Fantasy jazz label.

"There were a few tracks where we really hit it, but generally it was a disaster, murder on the poetry. Musicians were like, 'Man, go ahead and read your poems but we got to blow.' So the poet ends up trying to be heard above the din, like he's hawking fish on the street corner."

He believes the audience for poetry today is bigger than ever, but he is dismissive of the "ranting tradition" and the more recent genre of spoken-word performances which are often undiluted, ill-formed diatribes.

"And if you open up any modern poetry anthology, about four-fifths at least is really prose in the typography of poetry."

What he hears mostly is alienation among young poets: "The Beats were non-violent anarchists, today there is quite a violent feature to it and rap poetry is a good symptom of it." The average rap poem, he says, is a pure stream of alienation.

Ferlinghetti's poetry communicates through plain-spoken language, like the man himself.

When he asks if New Zealand is "not like rural England any more?" he recoils at the suggestion it has become more American since he visited briefly in 1973.

"I'm afraid to hear that. The American corporate monoculture is making every place the same. I suppose downtown Auckland looks like an American town. Travel becomes narrowing rather than broadening. It's American imperialism sweeping the Earth. The Roman Empire is nothing compared to the American empire today."

As a registered Green voter who supported consumer activist Ralph Nader, he is dismissive of contemporary American politics.

"Our Government is one with two right wings and there won't be any improvement until there's a Great Depression like 1929 because everyone is too well fed. But of course nobody wants another Great Depression, not even me, so whaddya going to do?"

He sees fewer avenues for dissent today than even during the conservative atmosphere of the 50s. People like the political critic Noam Chomsky cannot get on commercial television and he bemoans the centralisation of electronic and print media into fewer and fewer hands.

He notes San Francisco's Examiner has just bought the Chronicle, "so this is going to become a one-newspaper town and that's what's happening all across the country; the television stations are consolidating into conglomerates. It's terrible what's happening to the media."

If the 50s were somewhat myopic, he says, things are more dangerous now because the media is more controlled and consolidated.

"In the 50s nothing was organised and the climate was repressive because we had Eisenhower, but even he warned of the power of the military industrial complex. But there was no organised control the way there is today, it was piecemeal and scattershot. We now have friendly fascism."

He writes a monthly column in the San Francisco Chronicle Book Review where his enlightening essays -- under headings such as Poets as Freedom Fighters, Poetry Seen As Raw Thought and Poetry Transcends Nationalism -- reveal him as informed and politically astute.

Ferlinghetti was always considered and practical, the level-headed hipster while others of his Beat Generation spun out into booze, faux-Buddhism, LSD, heroin and Zen-lite.

In Kerouac's autobiographical novel Big Sur, Ferlinghetti appears as Lorenzo Monsanto, who cajoles the Kerouac character into giving up the drink if he wants to achieve anything of literary merit.

Ferlinghetti may be a Beat poet but he is also a businessman, publisher, activist and nothing if not pragmatic.

Does City Lights, which stocks "half a dozen CDs," carry the offending A Coney Island of the Mind disc, for example?

"Oh yeah."

Jake Walton - May 26, 2011

stop being a grumpy old man

Savepost a comment