Graham Reid | | 2 min read

Recently, while sitting in airport lounge in Sydney waiting for a flight home, I glanced up from my hardcover book and surveyed the other travelers in my immediate vicinity. Everyone of them – perhaps 40 in total, of all ages from preschoolers to the elderly, from diverse backgrounds and cultures – was on some kind of electronic device.

This our world, the one where Facebook has 845 million active monthly users, half of whom will sign in every day, sometimes to offer inane and inconsequential thoughts for “friends”. Beyond and behind that artificial world is another, where people role play, adopt fantasy avatars and a second life, trawl chatrooms for cyber sex and sometimes hope for a real encounter with the one typing back.

And when the electronic world collides with the real there can often be tragic circumstances.

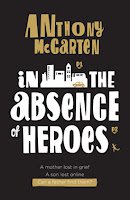

In Anthony McCarten's second novel which swirls around the deeply flawed and desperately sad Delpe family (formerly of New Zealand in the previous Death of a Superhero but the setting now shifted to England as he explains in a brief note at the start) the various worlds of grim reality, role play and online personae bounce off each other and intersect with tragic consequences.

Here is a couple torn apart by grief after the death from cancer of their young son Donald a year previous, his brother Jeff disappearing into cyberspace as a retreat, and mother Renata cloaked in pain and online looking for answers on a Catholic-run site where her counsellor goes by the screen name “God”. Her husband Jim struggles to hold together a job, the relationship with his emotionally distant wife and a surviving son who flees the unravelling family.

The Delpe's world becomes increasingly dependent on cellphones and computers as a substitute for real communication, the fantasy game Life of Lore where Jim signs in anonymously to find the missing Jeff now living there as a character called Merchant of Menace, and of a blurring of lines between emotion and reality, the factual and the fanciful.

If their real world is visceral (graphic and raw sex, bloody encounters) the one on the screens is no less so, but infinitely more dangerous to their well-being as they all discover when their various characters collide.

McCarten pulls the reader into this family's web but often overplays his hand with metaphors and similes where thought are like radio waves, the world is pixilated and we SatNav our way through life.

But it is the human sadness at the heart here – of a marriage broken by grief and sliding into anger and indifference, of a teenager so desperate for love and understanding he phones his dead brother and becomes a slave in cyberworld – which draws you in to these landscapes populated by the lost.

If the improbability of some of this – and peripheral characters who sometimes seem little more than ciphers or metaphors themselves – feels strained, we need only look up from our books at what is happening all around us, and consider that 50 percent of people online lie about their age, weight, job, marital status and gender.

And that chilling fact, as McCarten wryly notes when quoting it – and other statistics at the start -- is sourced directly from . . . the internet.

post a comment