Graham Reid | | 2 min read

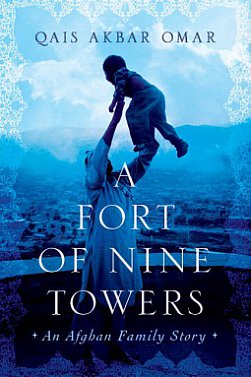

In an age when shaky images from phone cameras and newspaper reports cite Facebook comments or tweets as a substitute for news – that famous “first draft of history” as it was once known – this remarkably plain-spoken and often unflinching memoir comes as a rare combination of reportage, witness to history, family story and national tragedy.

When mujahideen fighters moved into his neighbourhood in Kabul in 1992 with the attendant factionalism, rocket attacks and gunfire, the author – then just eight – became one of those many anonymous souls who could, if they had the opportunity, bring us an unvarnished truth of their experience.

Latterly he became a translator for the US military and here writes in English with such emotional flatness and an eye for detail that we feel this is the authentic voice of the child who was there at his grandfather's compound which held the extended family, was surrounded and the family forced to take flight.

The childhood he evokes before the mujahideen and then the Taliban swarmed across the city seems almost an idyll of respect, faith, youthful games and humour: “Kabul was like a huge garden then.”

The large family, overseen by the benign, thoughtful and independent grandfather face privations then menace.

“The time of the Communists had ended, the time of the mujahideen had begun,” Omar writes.

“When I heard the mujahideen were coming I had expected to see heroes in uniforms and shiny boots. But they were dressed like villagers with big turbans, the traditional baggy pants called shalwar, and the long tunic-like shirts called kamiz. Their waistcoats were filled with grenades and bullets.

“They all had beards, moustaches and smelly shoes that wrapped up stinky feet; not one was without a gun. On TV the female announcers now covered their heads with scarves. Women singers were no longer seen. Instead we saw men with big turbans and long beards sitting on the floor, reciting the Holy Koran.”

So much of this is familiar today we forget it was a new phenomena to the people of Afghanistan. And briefly things were good under the new regime.

Then everything changed, the family buried what wealth they had and, jammed into a car, many headed off to the fort of the title, the compound of a family business associate. And then on further journeys to find refuge.

Throughout ordinary people are courteous, helpful (when their natural suspicion of traveling strangers are allayed), respectful and mindful of their faith. But the soldiers of various factions are painted as murderous thugs who behead at will, rape women, steal and commit random acts of indiscriminate violence.

The young Omar witnesses all this – there are terrible accounts of brutality and torture then sudden mood swings by heavily armed men who become apologetic – and at one point after further flight the family live in a cave behind the head of one of the Buddhas in Bamiyan.

That the Buddhas are no longer there is just another depressing fact in a story of survival and heartbreak that is utterly engrossing. At times there is humour, childlike delight in simple pleasures and occasionally flashes of bitter poetry.

“I had always expected I would see our Buddha again. But the storm of ignorance that has been raging in Afghanistan for so many decades smashed him to bits before I could return.

“I once lived inside his head. Now he lives in mine.”

post a comment