Graham Reid | | 3 min read

A few years ago when I was in Australia interviewing the re-formed Cold Chisel, I took a chance afterwards to talk with their songwriter Don Walker, who had written an exceptional, literary and darkly poetic memoir, Shots.

I wanted to ask him about something which had been troubling me quietly for a number of years: Why was it that so many Australian songwriters – Paul Kelly, Nick Cave, himself, for example – ventured so successfully into the literary sphere?

After that conversation – which was usefully inconclusive given Walker's particularly dry demeanor – I asked who in New Zealand rock culture might write a good book.

Without hesitation he replied, “Dave McArtney”.

It didn't make sense immediately but as I thought about it, the rationale was there.

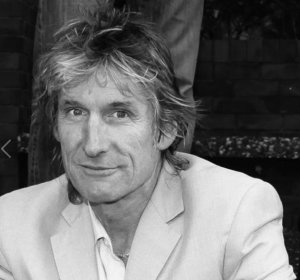

If, of the surviving frontline Hello Sailor members, Graham Brazier was the rebel-outsider who attracted trouble as much as he did admiration and Harry Lyon was the implacable rock, McCartney was almost a man apart.

On the few occasions I met him he was a gentleman and unfailingly polite, outside of music he had built another life, had always been at one with a more untainted world through a passion for surfing and skiing, and yet had been in that crucible of hard drugs, hard music and a free-wheeling lifestyle.

When Hello Sailor were inducted into the New Zealand Music Hall of Fame in 2011 it was noticeable that while rock'n'roll bad-boy Brazier got the big-ups from the crowd, Lyon and McArtney were gracious enough to stand aside.

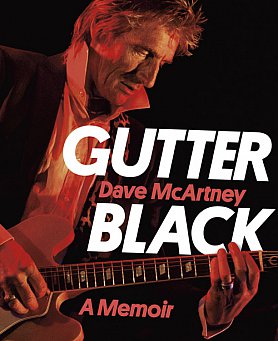

The more I thought about it, the more I believed he would write a good book. And with Gutter Black; A Memoir he almost did.

His death in April 2013 after he'd

delivered his manuscript has denied us an even better book which

might have come through the necessary editing and rewrite process.

His death in April 2013 after he'd

delivered his manuscript has denied us an even better book which

might have come through the necessary editing and rewrite process.

However there are passages – pages and pages even – where this story sings off the paper in flowing and sustained flights of imagery and imagination. But there are also irritating errors (eg. the year John Kennedy was assassinated) and unfortunate gaps (the spectral figure of Paul Hewson from Dragon and later McArtney's Pink Flamingos stalks these pages then suddenly disappears without explanation that he died in '85 and what that must have meant to the author).

But aside from that – and the narrative turning from first to third person in places, writing as if Hello Sailor were a separate entity in the story – there is an enormous amount to enjoy and admire here, not the least McArtney's candor.

Although there is doubtless much more which could have been said about the darkness and debauchery, as Ravi Shankar said of his own autobiography “a hint is enough for intelligent people to understand”.

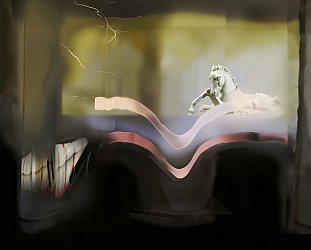

That said, McArtney lays out more than mere hints and the furiously imagistic writing about his near death from an OD is as compelling as when he writes about being electrocuted on stage.

Of the latter he starts: “I floated. I . . . I? What was I now? I remember that I didn't seem to be interacting with my environment. I was part of it. All was one. What followed was an awareness, a sensation, of something happening. A vivid picture, a transferral, a journey, of flowing, suspended in a river of light, over a swaying field of golden corn. Joyfully warm, sunshine-bright, yellow corn. Music, an underwater symphony, breathed gently some eternal themes . . .”

And when he writes about the grubby world of bars, clubs, their notorious Mandrax Mansion and temporary home in Hollywood Hills, it is with a brutally observational eye.

Here's Indian Cheryl in LA: “The eyes rolled back some more then shot back with sudden precision, fixing me with a stare. From the liver spots and pimples on her glabella to the dimpled gloop of her chalky cheek, there was history in that stare. It was that moment again – just you and her, and human frailty. And the Navajo nation. I felt a warmth come to fill the gap left by the massive high of the cocaine injection.

“ 'Wanna 'lude?' she whispered into my ear.”

Gutter Black is full of finely focused writing like that which takes you into the moment, whether it be Hello Sailor on stage or embattled by drugs, money and impending doom, of the special bonds of brotherhood these musicians shared, of the sheer joy of riding a wave on an empty ocean, of his life in Germany . . .

Dave McArtney was a rare -- and modest -- man as these

pages attest. Few among his peers having been through all that he did

would study and finish a Masters degree in music, live to enjoy the

love of family and the respect of peers and strangers alike.

Dave McArtney was a rare -- and modest -- man as these

pages attest. Few among his peers having been through all that he did

would study and finish a Masters degree in music, live to enjoy the

love of family and the respect of peers and strangers alike.

One of the most moving parts in the book is the epilogue written by his wife Donna who closes these pages with a clarity, compassion and frankness that may surprise many.

Gutter Black tells a great rock'n'roll story and, more than that, the life of a special man in his time. It is perhaps not quite the book it might have been, but it is certainly a far better book than we might have expected.

I hope someone sends Don Walker a copy.

Gutter Black; A Memoir (Harper Collins) is available from May 1. $44.99

post a comment