Graham Reid | | 7 min read

The beer cartons were dumped on the writer’s verandah “like an hermaphroditic orphan.” Inside were random jottings, diary entries, what appeared to be short stories, poems and events in a life which may – or may not – have taken their author across the globe from Samoa and Auckland to Israel and the United States.

And accompanying this flotsam of a life is the note, unsigned, undated but with a powerful imperative the writer cannot refuse.

“Out of your reshaping of the jumbled contents of my three cartons I hope to read/find a meaning to my wasted life.”

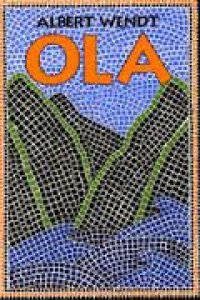

So begins the new novel by Albert Wendt – his first for a decade - and the elusive nature of finding truth among the fiction starts right there in the foreword.

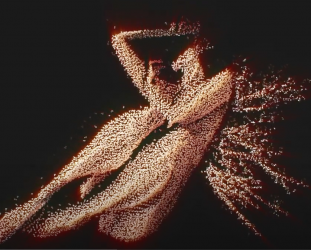

Wendt is not the writer in receipt of the cartons, of course, the premise of the novel Ola undercuts readers’ expectations. And the central character Ola may (or may not) be a woman who may (or many not) have invented the son Pita she writes about. Yet in spite of such seeming complexities. Ola is a novel which glides easily between these questions about the nature of fiction.

Its unifying thread is its cosmopolitan

reach. Here is a novel which traces a pilgrimage to Israel, follows

the lives of a woman from Remuera and her children, tangentially`

incorporates sections in Northland and New York but begins and ends

in Samoa.

Its unifying thread is its cosmopolitan

reach. Here is a novel which traces a pilgrimage to Israel, follows

the lives of a woman from Remuera and her children, tangentially`

incorporates sections in Northland and New York but begins and ends

in Samoa.

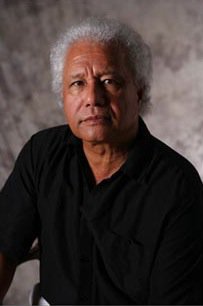

In that breadth of vision, Wendt sees his own reflection. “Oh I write a lot about my trips,” laughs the 51-year old author in his office in the English Department of Auckland University.

Before the conversation turns to his novel there is a lengthy discussion of China, where he spent a too-short two weeks. He weighs his words cautiously about what he saw and says he had to continually remind himself that this was Third World country he was travelling through.

“You see it in the hotels, all the latest plumbing – but it often breaks down and no one can fix it. You see that in most Third World countries around the Pacific region, too. But after a while you get used to it and say ‘well, this is the Third World so I have to expect the planes won’t fly on time.’ But when China gets moving, then...”

Listening to Wendt’s free-ranging conversation is a reminder of the scope of his vision and ideas which seem effortlessly within his grasp.

He is delayed for half an hour, his old friend Tupuola Efi, the former Prime Minister of Samoa, has dropped in unexpectedly and Wendt can’t be photographed tomorrow because he has to fly to Wellington for a meeting of the New Zealand Qualifications Board. His bookcase is stacked with writings from the Pacific, Australia and China. He teaches and writes...but keeps his distance from the world of academia in a few key respects.

He seldom reviews books anymore and speaks with some bewilderment of the internecine sniping of academics who do so and who score points off rivals through their criticism. He seldom delivers or writes academic papers anymore. The principles they work from and the language required divert him from his own writing.

Wendt writes all the time, even gets irritable if he doesn’t he laughs. But he feels little need to publish. “People are worried that I haven’t been writing.” He laughs, then outlines the half dozen books he has as present projects.

There is Vela (“a long verse piece which will take the rest of my life” he says in earnest), another novel even older than Ola, Black Rainbow and its sequel (“The sequel is almost finished and I have the outline for the third part”) and a few other ideas.

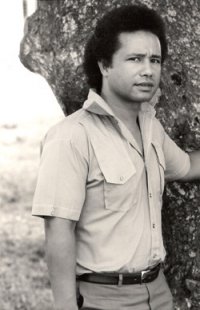

Yet a reading of Ola and the way it shifts easily between characters, continents and ideas would suggest that Wendt is writing quite a different way now than when he was a 34-year school teacher alerting New Zealand literary culture to the Samoan perspective in his novel Sons For The Return Home.

THE activity of writing and revising means he has an accumulation of pieces which need constant attention and shaping. Ola provides the vehicle for him to bring a number of these pieces, not separate or disparate, into the one broad sweep. That device, of operating within fiction but on the border of imaginary non-fiction allows him to assimilate myth and narrative while having the reader party to the piecing together.

“Our lives are made up of bits and pieces and aren’t novels, although we might all wish they were. In Ola we have some guy piecing together this life and bringing order, and a novel, to her life. But this guy is making it up too, the order would be different if someone else was rearranging the pieces.

“I prefer now to have two or three novels within the same book. The long section on New Zealand in Ola was originally twice the length, but I revised it back.

“It was long because it was written when I had all the time in the world because I was on a writing fellowship. These days I am only able to work part-time so the work is not so sustained.”

The layout of Ola – some pages with but a few words or a snatch of a poem by the fictional Ola – was designed at Wendt’s insistence. To run chapters on would have been to rush the visual pace and it is a book which he says has to breathe.

That also meant, however, that it would have been an expensive hardback because of its size (“around $50 and who in New Zealand has that kind of money today?” so it comes out in a special, large format paperback.

Yet Wendt has, in some ways, let the book go already. Some of the interconnecting sections were written a long time again and he has already moved on Black Rainbow is ready for publication, he says.

Despite Ola being so long in the writing, Wendt identifies very clear perspectives he was exploring. It is significant the central characters, whether they be in Samoa, Israel or New Zealand are all in their 40s.

“The genesis was in writing about this character surviving these marriages and the events in her life although I tried twice to change the narrator into a man...but the book wouldn’t allow it. In the end I had to trust my intuition on that aspect.

“I also wanted to look at my generation, the generation now in control, and this was an attempt to write about my own experiences through middle age.

“People like Ola and myself have been through the systems and have done a lot of this multicultural living so some of the characters are drawn from life and others are composites. But it is a novel, and anyone writing a novel is attempting to make themselves and the things around them more real...but then again, Ola is all made up.”

Wendt’s neat sidestepping around the fiction at the centre of Ola – and Ola – allows him to include a mythic dimension epitomised by Ola’s father, Finau, and his pilgrimage to Israel, the land of his faith, yet home to Jews whom his faith has intuitively taught him to mistrust.

A visit to Israel allowed Wendt to observe the interaction of Western and Eastern Jews at first hand, their common ground and the fundamental questions of the relationship between vanquished and victor.

The question of Palestine is deliberately left hanging in Ola...a question raised by one of the more distant characters in the book, Ola’s possibly fictional son, Pita, who is studying “modern physics” in America.

“The younger characters in the book are more focused in what they do. The girl Shona finds herself through discovering her culture, and Pita works through physics, which is something I was very keen on at one time.

“The argument that to understand your culture you must go back to the roots is very true – but you must understand modern physics also. That is the obvious truth of the Japanese experience.”

In the space of a breath Wendt easily

digresses into the incremental growth of Japanese technology and the

culture which has sprung it. A recent convert to the possibilities of

word processors, he enthusiastically discuses the shifting of copy

but confesses to still writing sustained sections of prose in

longhand.

In the space of a breath Wendt easily

digresses into the incremental growth of Japanese technology and the

culture which has sprung it. A recent convert to the possibilities of

word processors, he enthusiastically discuses the shifting of copy

but confesses to still writing sustained sections of prose in

longhand.

He effortlessly moves the discussion on to note how cultures define themselves by what they have lost (“you see it in Maori writing, novels like The bone people and The Matriarch”) and how cultural perspectives determine what readers will take from Ola.

“People who have read it already have said how they have enjoyed the different sections.

“New Zealanders have liked the New Zealand section and the Samoans have been taken with the relationship between Ola and her father. And at the end do you think Ola will accept the title of Lagona from her father?

“If you were Samoan, that’s the only ending. Her father has made her an offer she can’t refuse.

“That’s where the different perspectives come in. But Ola is not happy. She can’t be...and none of us will be.”

“But the key thing for me with Ola was in finding her a name. When writing it originally she didn’t have one and then I wondered what this character would be like if she had been born after her mother died. What would she be carrying with her if that happened? So I came to Olamaiileoti, which means born from death, and that shortened was Ola.

“Ola means life-force and that is the name of the journey she makes in the book. And it is the name of the journey we must all make. Ola is the journey of life.

post a comment