Graham Reid | | 5 min read

There's Led Zeppelin on the jukebox, a few old soaks at the bar, a pool table in the corner and a handle of beer in front of him. Craig Marriner seems right at home in this world as distant from literary pretension as is possible.

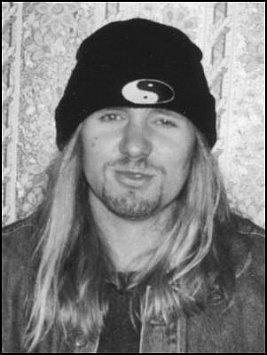

At 27, his long, blond hair tied in a ponytail, Marriner fits the profile of one who might know the violent world of dope dealing and life on the edge that is the backdrop to his debut novel Stonedogs.

Appearances are deceptive, of course, and while Marriner's life is punctuated by time in Australia's unforgiving outback, working illegally in London, and smoking dope in the hash houses of Amsterdam, he's far from some got-stoned-and-missed-it dropout. His relaxed, expletives-included conversation betrays a keen intelligence and a lifetime of voracious reading. He's candid, focused, literate and likeable in a no-bullshit way.

So we roll cigarettes -- "chokers" as he calls them -- and order a couple more beers before we get down to it. No worries, mate.

Marriner's life is as colourful -- mercifully not as brutal -- as that of the main character, Gator, in his novel, which is initially set in the dope-dealing street culture of Rotorua, a world he knows well.

"Yeah, I'm a Rotorua boy born-and-bred, strictly working-class background, my dad was a bushman until he was laid off," he says, unapologetically. "And I've got a supportive older brother and sister who've both lived conservative lifestyles - whereas mine has been anything but."

By his own account he was good at history, English and geography at school but pre-empted expulsion in the 7th form by quitting ("I was on the edge of the rails by then") and subsequently spent six months getting stoned and partying. Then he heard from his father in Australia for the first time in 10 years and decided to join him goldmining at remote Mt Magnet, a dot on the map in Western Australia five hours inland from Geraldton.

"My dad was a hard man and a 'rock-dog'. He was supposed to get me a job but got sacked for drinking which meant he couldn't work in the town so he [expletive deleted] off. I saw something advertised doing [geological] sampling so thought I'd give it a lash, I had good school grades. So I lived there on and off for three years and did a fair bit of growing up. I was 18 and I'd never even worked part time.

"But it was good, you get a lot of fights but mostly between the big bulls who want to show off. There's always a bit of banter and a joke going on, and I like Australians for that."

After four years he returned to New Zealand with a fair bit of money and a girlfriend, so he bought a caravan and a ute and they cruised the North Island for six to eight months. The relationship fell apart and, as Marriner continued his itinerant surfing and snowboarding lifestyle, he recognised all he'd really wanted to do since high school was to write. Now he had the financial luxury to do so, and time on his hands. He all but completed a science fiction trilogy but it went on the back-burner when he headed to London.

"I worked various jobs there, went round Europe a few times, down to Turkey, went surfing down the coast to Morocco, and to Amsterdam about six times where I had a friend so had the inside running behind the commercial tourist facade and got into the underground rock clubs.

"I was in Europe about four years, but had to leave in hurry because I was working illegally in a warehouse in London and the boss did a check on visas. So I came home and started to write again."

He hauled out his sprawling sci-fi

novel but realised he had outgrown the genre. And so Stonedogs, which

distils experiences of gangs in Rotorua, and the drug scene in

Amsterdam and Auckland among other things, was born.

He hauled out his sprawling sci-fi

novel but realised he had outgrown the genre. And so Stonedogs, which

distils experiences of gangs in Rotorua, and the drug scene in

Amsterdam and Auckland among other things, was born.

Stonedogs is a spiralling, violent narrative of a complex dope deal which goes wrong, and its characters are drawn in the hard lines of a reality Marriner has known. There are twists which have already drawn comparisons with a Quentin Tarantino movie, and it is written with a keen sense of place and an ear for unadorned dialogue.

But, given how endemic marijuana is in New Zealand, Marriner is surprised at how seldom it has been used as a vehicle into that underworld which frequently manifests itself in mainstream society when a deal goes wrong, or police and lawyers are caught up. However, if Stonedogs were only a streetwise view of the intersecting worlds of the dope dynamic, that would hardly set it apart.

"Initially it was almost a madcap comedy satire in the Hunter S. Thompson style but then I matured and wanted to move it more in the direction of an arthouse novel. I saw all kinds of other angles I could mix in."

So behind the racy narrative ("I wanted to deliver the last third as a thriller") are the unusually intellectual motivations of the main character and probes into his disturbed, but often disturbingly lucid, psyche.

There's an anti-capitalist heart beating in Gator and a nascent neo-Nietzschean idea within his philosophy of the "fiendish beast" which lurks within Man. According to Gator, it manifests itself as Hitler, the US cavalry bringing genocide to Native Americans and in the atrocities in Bosnia. At some points Stonedogs comes off as a kind of Clockwork Orange-meets-Once Were Warriors as imagined by Irvine Welsh.

"I've been pretty disillusioned with mainstream society for a while, I just don't see a future in it. And I've been moving in working-class circles and watching the quiet desperation everyone lives their lives through. So the novel comes from there, and questions where we're going environmentally and politically. And drugs might have a lot to do with it, just having friends around and smoking a joint and philosophising."

Dopers' paranoia then?

"Definitely," he laughs. "That's something inherent in the drug."

Structurally Stonedogs is unusual. Some text takes the form of a play with stage directions, there are sudden shifts from narrator's voice to outside observer, pages of inner narrative are italicised ...

"It was important to do something that would be seen as innovative in terms of structure and format, to come up with mediums which are slightly alternative to what's been done. I saw devices which hadn't been used and I couldn't see why they hadn't."

For many, Stonedogs will seem overwritten, the tumble of polysyllables and deliberately elevated language ("Mick has relinquished driving duties in search of liquid solace") sitting uncomfortably alongside dialogue which Marriner has heard described as "gratuitous". Faint-hearted readers might wish it came with a censor's warning.

"When I wrote it I wanted to remove the PC thing and avoid apathy and indifference to it. As long as I got a rise one way or the other I'd be happy. But I've been surprised how many older people have enjoyed it. I think they like being given a portal into world which they know is taking place around them but have never had a medium to look into it."

The draft of the first chapters captured the attention of literary agent Michael Gifkins whose name Marriner found on the New Zealand Society of Authors' website.

"He wanted to read the rest and I could tell he was pretty blown away. He thought it was new and fresh but a bit rough.

"The ending was a little different and he wanted one more in synch with the politics of the novel, but other than that he really did bugger all. And then we sent it to Random House who took it. In hindsight it's been bloody easy."

That was four months ago and he's been back in Australia, stacking up the bank balance with more mining work. So he is off to London soon to research an idea he says is waiting to be plucked.

"I'd like to be seen as a Kiwi art house youth culture-type writer, that's the niche I'm hoping to slide into."

post a comment