Graham Reid | | 3 min read

I Want a Heartbeat, Johnny Marr 2012

Sometimes a simple, bare fact can make you stop dead. Like this one: Johnny Marr was 23 when the Smiths broke up.

As he writes in this unadorned and often flatly emotionless autobiography, “I had no idea what I was going to do”.

It's a measure of the depth and detail of this 420 page book that the first third is of his life before the Smiths formed in '82, the central third about the five years of the band's existence and the last of the almost three decades since. He's been an ex-Smith for nearly six times as long as he was in the group he founded in his late teens.

And he makes clear the Smiths were his group: He founded the band, invited in Morrissey (who named the group) and during their remarkably short but productive lifetime (a dozen non-album singles and four studio albums in fewer than four years) he was mostly the manager in all but name.

Decisions about the band were made with singer/lyricist Morrissey – Mike Joyce and Andy Rourke seem incidental – but the band was his.

Which made it all the more hurtful when the break-up came in '87 and it was a three-against-one split. He says it was over the recent appointment of Ken Friedman as manager and rather weakly allows that while making the Strangeways, Here We Come album “something suddenly changed. New allegiances were being formed between band members . . . everything I saw as good management they saw as interference and giving up control . . . this new feeling of opposition seemed like it was turning into a kind of domination with our friendships now appearing to be a secondary consideration . . .”

And that's what he says about the end of a band many consider to be the most important British group of the Eighties, and maybe even beyond.

So you don't come to the end of this book feeling any great sense of enlightenment about the internal dynamic of the band (if Marr ever made a lyrical contribution or had an opinion about Morrissey' writing beyond that the songs were good you aren't told).

But then again . . .

In the weeks after the break-up when he enthusiastically embraced the uncertain future (so he says) the phone started to ring: Talking Heads first and then Paul McCartney.

He was star-struck when playing with McCartney but also took the chance to discuss with him the events of recent months because “I had a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to get perspective and insight from a man who actually knew my situation. A man who had been defined by his relationship with his songwriting partner and whose band's break-up had hung over his every move . . .”

McCartney listens and then offers his evaluation, “That's bands for ya”.

Flashes of humour like

this – we might say “Northern humour” and sometimes bald

assessments – run through these pages and that first third is

fascinating as the boy obsessed with clothes, his hair and guitars

grows up in grim urban Manchester.

Flashes of humour like

this – we might say “Northern humour” and sometimes bald

assessments – run through these pages and that first third is

fascinating as the boy obsessed with clothes, his hair and guitars

grows up in grim urban Manchester.

When he describes his early life in the Sixties – very Catholic, outdoor toilet, a tin tub for bathing in front of the fireplace, kids playing in grey streets – it sounds uncannily like George Harrison's life in Liverpool two decades previous. Manchester even into the Seventies was like a city still post-war.

If piercing insight about the Smiths is absent – and he appears to want to avoid opening any old wounds or a further feud with Morrissey – then the rest of the story makes up for it in his flat, unadorned candour about his dangerous drinking at one point (a bottle of wine and half a bottle of tequila and no licence is a bad combination that almost kills him one night while out driving) and some cutting assessments.

This on Labour leader Neil Kinnock and “the showbiz nature of politics”: "[He] made his entrance with a smile so wide you wondered how he'd managed to squeeze his face through the door. His confidence was incredible as he sucked every bit of attention from the room. If Liberace and Diana Ross had been fighting naked and on fire in front of him he still wouldn't have noticed. It was then that I decided that most politicians are ultimately fame hounds.

“They may have the rhetoric and may even stand for the right things, but they're more than a little ambitious and they're definitely more than okay with being famous.

“They just weren't cool enough to be musicians and not good enough to be footballers.”

So here – dealt with in that kind of prose – are chance encounters which become warm friendships (meeting Zak Starkey in a lift, Neil Finn and family), an astonishing roll-call of legendary artists, awards (“a funny thing, you wait for 30 years for one to show up then a load of them come at once . . .”) and music, bands, music, travels, more music and then even more.

A quick read, for sure, and the creative process largely goes unexplored. You get the impression he just plays around on guitar and great songs come.

Maybe they do and that's all there is to it.

That's music for ya?

But Marr comes off as a genuinely nice fellow you'd be happy to have a drink or two with, and suspect you could. But if you did you might not get too many insights about the Smiths – who to be fair occupied an increasingly smaller and smaller part of his life – even if it were over a bottle of wine and half a bottle of tequila.

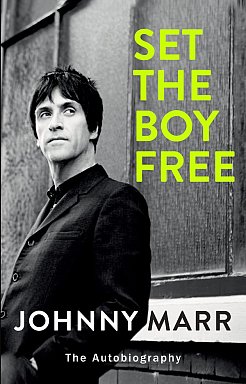

Set the Boy Free by Johnny Marr, Penguin Random House. $40

post a comment