Graham Reid | | 5 min read

Sometimes when I am talking to my university students about the rise of rock'n'roll in the Fifties – the first musical genre to specifically target teens – I tell them, just to get their attention again, that my parents were never teenagers.

They look bewildered and so I explain: my mother in Scotland left school at 14 and my father in this country at 15, and both went to work to support their families. Of course they had “teen” appended after their age but – and here I resort to cliches about teenagers they understand. They were young versions of adults (dressing and acting like people years older) and never had the luxury of moping around in the bedroom saying “He/she doesn't love me” or being sullen and moody and uncommunicative.

In the Thirties and Forties teenagers as we understand them today – that identifiable demographic with its own mores, clothes, identification and so on – just didn't exist.

Of course they did have friends their own age in common and to some greater or lesser extent identified with them, but nowhere near to the way that happened after the Fifties and which continues to this day.

Unfortunately this otherwise excellent, readable, insightful and well illustrated history steps back just as New Zealand teenagers were emerging as a powerful economic and social powerhouse in the Sixties.

Financial independence, a stable and peaceful political climate, full employment and post-Beatles cultural shifts among other factors meant that teenagers, and those who would exploit that huge baby boomer demographic which turned 14 in 1960, would drive popular culture in way we had never seen before.

And it would remain that way thereafter.

In

his conclusion here Chris Brickell – an associate professor in

gender studies at the University of Otago who wrote, among other

books, Mates and Lovers; A History of Gay New Zealand almost 10 years

ago – writes of his own teenage years in the late Eighties and in some measure how he and his peers saw the world.

In

his conclusion here Chris Brickell – an associate professor in

gender studies at the University of Otago who wrote, among other

books, Mates and Lovers; A History of Gay New Zealand almost 10 years

ago – writes of his own teenage years in the late Eighties and in some measure how he and his peers saw the world.

He also notes that the term “teenager” is a pejorative label slapped on youth by adults (as I deliberately have done to make a point), and most often in a derogatory way which implies fecklessness, clue-less know alls and so on.

But then in previous times the words “larrikin” and others now fallen from common currency also had similar connotations.

His history of young people in Aotearoa New Zealand – and the word youth is mostly preferable to teenager in this account – starts back with the first settlers (he accommodates Maori youth throughout however) and identifies the pleasures and trepidations of those young people who made that arduous two-month voyage from Great Britain to these distant and unknown shores. Some, as he notes, with an average of 17 who has engaged in petty theft and ended up in Pankhurst Prison on the Isle of Wight only to be deported to this country.

“The Pankhurst boys' experience tell of youth finding their feet in a heady atmosphere of moral judgement, but they also reflect the continuous mobility of boys' working lives.”

And in colonial days boys – and to some extent young girls – were itinerant, moving from job to job (or service positions in different households) and of course some were ne'erdowells.

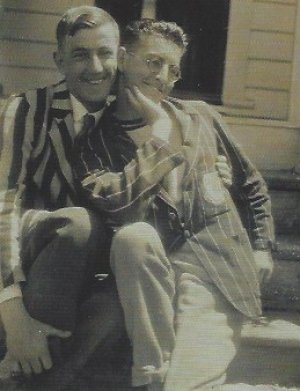

Through diary entries, letters, historical record, statistics and telling anecdotes, Brickell paints a lovely, highly readable and informative account of the distinct if not always distinctive culture and companionship of young people down the decades.

In these pages we learn fascinating facts: with parental agreement girls could marry at 12 in the late 19th century; at the end of the 1860s 60 percent of all female workers were domestic servants (many ill-equipped) and “more than a few goldfield girls sold sexual services to the miners”.

These

pages come alive when, as he frequently does, Brickell introduces us

to people by name and we get to feel their presence through their opinions and exploits, some in

the latter case enjoyably rebellious.

These

pages come alive when, as he frequently does, Brickell introduces us

to people by name and we get to feel their presence through their opinions and exploits, some in

the latter case enjoyably rebellious.

Margaret Glen for example at 14 was already identified as leading a depraved life and consorting with prostitutes (she was jailed for a year) and Eliza Lambert of the same age just was just never going to fit in: she arrived in 1859 and hung around Christchurch's Gloucester Theatre using foul language and throwing stones at the hotel window. She was in and out of jail.

Through insert pages into the narrative overview we encounter such characters as 18-year old Thomas Gleeson who was an accomplished thief using multiple disguises (stylish gentlewoman or a man with a clip on beard!).

There are also however accounts of the hard-working, the scholars, the arduous lives of farm and factory workers (who were never “teenagers”) and how young people would increasingly congregate together – sometimes through emerging youth organisations – and find a common identification with their peers.

Those who bemoan youth tribes today should turn to the pages about larrikins, flappers, mashers (latter day dandies and aesthetes who avoided manual labour in favour of “caramels, cigarettes and late hours” according to a contemporary description), dudes (and dudines) and dandies to get some greater perspective.

Clothes then, as now, became visual signifiers and frequently we are reminded just how small the European population of this country was 175 years ago: the whole of Otago had only 620 Pakeha inhabitants in the 1840s and Auckland about 3000.

Yet just four decades later there were over 22,000 in Auckland and 28,000 in Wellington. Dunedin, because of the gold rush, had over 45,000.

Brickell

accounts for the Maori population also – Maori schools, young Maori

men dressed like Oxbridge undergrads, others in training schemes,

young women is domestic service or schools – but there is one

curious skew to this otherwise excellent book.

Brickell

accounts for the Maori population also – Maori schools, young Maori

men dressed like Oxbridge undergrads, others in training schemes,

young women is domestic service or schools – but there is one

curious skew to this otherwise excellent book.

In his expansive and inclusive overview he rightly cites stories, examples, institutions and characters from all across the country, but very rarely from Auckland which, as increasingly the largest city in the country with considerable diversity and a booming population of young people, must surely have contributed to this story.

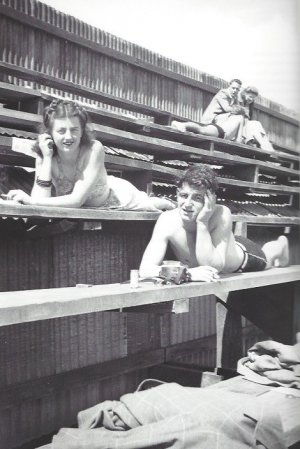

Auckland was certainly home to many bodgies and widgies (and a small jazz-loving and aspirationally bohemian beatnik population) in the Fifties and Sixties, and yet the city and its youth/teenage population which worked in factories and shops, went to very diverse schools, laboured on nearby orchards and farms, became rebellious or attended tertiary institutions gets scant attention.

Very curious.

Otherwise however the breadth of Brickell's research and historical narrative is admirable: he allows for youthful liaisons (hetero and homosexual), the outsiders and conformists, cultural niches amongst immigrant youth from Europe, church groups and gangs of milkbar cowboys, teenage language and clothes . . .

If the story implodes with some suddenness in its closing overs of this long game just as those teenagers of the title are truly emerging in numbers, strength and specific identification as distinct demographic, that takes nothing away from all that has preceded it.

Mashers?

Who knew?

Thanks to Chris Brickell, now we all do.

Teenagers; The Rise of Youth Culture in New Zealand by Chris Brickell. Auckland University Press $50

post a comment