Graham Reid | | 3 min read

Not this guy, I twice declined the opportunity to do a phone interview with him because . . .

Well, it was the late Eighties and mid Nineties and he wasn't just cantankerous about his obvious genius not being recognised but also would subject interviewers to some interrogation before they could even start their questioning.

I was of the opinion that I had exactly the right amount of aggravation in my life and so I didn't need his . . . and anyway, the current albums on each occasion weren't much cop and he refused to discuss the other recent good ones.

As it happened – as when an enthusiastic young woman from a record company said a phone interview with the great but grumpy Van Morrison was possible, yeah riiiight – the phoners never went ahead anyway.

Reed would have nixed the idea at inception.

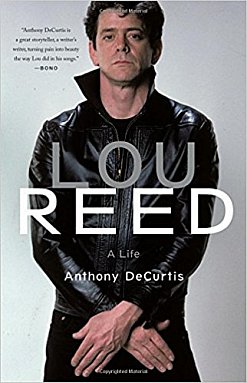

Having read Anthony DeCurtis excellent, insightful and very detailed biography I do slightly regret my comment at the end of that article about the silly old duffer falling asleep next to me while Laurie did a fascinating spoken word presentation about her involvement with NASA.

He was obviously unwell and fatigued by Hep C and liver damage, which resulted in a transplant three years later.

But not so unwell that he didn't deliver a sometimes exceptional re-interpretation of Metal Machine Music with his MM3 trio of sonic excess and improvisation.

The old boy – actually only 68 at the time – could still challenge.

People walked out. I stayed until the end.

And if you have ever had any interest in Lou Reed – beyond Walk on the Wild Side, or maybe even only that – then DeCurtis' biography is far superior to previous ones and you wil certainly stay until the end. (My shelf has three previous bios, one by the estimable Pete Doggett and two by Warhol camp-follower Victor Bockris).

DeCurtis would sometimes encounter Reed – and in later days when Reed became a more amenable public figure, with Laurie Anderson – so met the notoriously fractious musician/poet/writer and pugnacious personality at his best.

Or at least, not at his worst.

DeCurtis – who wrote for Rolling Stone but is a respected academic in creative writing at the University of Pennsylvania among many other credits – not only has the nous to get inside Reed's many personalities but the chops to dissect his writing and music.

And he had considerable access to former bandmates, fellow travellers, whether they be denizens of Reed's dark world of sex, voyeurism and drugs or writers, students at Syracuse where Reed graduated in literature (and didn't let anybody forget it, you'd think he was the only one with a degree), former lovers and wives, and so on.

So his biography is insightful and in-depth.

Most rock biographies almost inevitably default to an album-by-album consideration of an artist's career (and revert to reviews or press releases) and although that is slightly true here too – that is the artist's public life after all – DeCurtis places the albums in the context of Reed's private world, weaves in commentary from musicians and Reed himself, and discusses individual tracks in a very enlightening way.

(I've been going back to The Blue Mask and Mistrial but nothing will induce me to endure Lulu with Metallica again . . . maybe I need to give it time, DeCurtis almost makes a case for it.)

The story has a tragic subtext: Reed's hatred for his parents (notably his father) for accepting medical advice he should have electro shock treatment when he was “acting out” as a willful, sexually exploratory teenager . . . a guilt they lived with all their long lives and which Reed would jump in and out in his aggressively accusatory way.

He also turned that into self-loathing.

If Lou was the survivor then his long suffering parents were just as much so. His mother Toby outlived him by 10 days.

Whether it be Reed's belligerent personality, him sucking ideas and experiences out of others (poet Delmore Schwartz, Andy Warhol and many others) or being the dutiful and sometimes doting partner/husband to companions (aside from the gender-fluid male Rachel, Reed was drawn to clean living preppy and traditionally beautiful All American Gal types . . . to corrupt but rey on?) or Reed's changing personalities (in his last two decade '”sweet” is the word that occurs the most from friends and casual acquaintances) – DeCurtis is unflinching.

Flaws and truth are there alongside the widely received fictions, and sometime the facts are abrupt.

Reed complained all his life – to record companies, journalists and anyone prepared to endure the shouting – about how little money he was making, how few copies of his solo albums sold. (All true, DeCurtis offers the pitifully small numbers).

But when he died he left an estate worth US$30 million, among the properties were his Greenwich Village apartment (US$7 million and the Hampton estate of $US1.5 million).

Lou Reed walked on the wild side, loved little dogs, practiced tai chi, could be a gracious host or a belligerent house guest, would turn on people in an instant and was a true friend to his may friends who succumbed to killing illness.

He was a sometimes anti-Semitic Jew and would sometimes dismiss his former self as “a fucing faggot junkie” . . . and practiced meditation.

Lou Reed demanded respect . . . and by the end of these 500 pages you might even be prepared to give it . . . if you didn't already.

Anthony DeCurtis has persuade me I wrongly dismissive of the Live in Italy album.

But let me know if Lulu is worth going back to.

Lou Reed; A Life by Anthony DeCurtis is published by John Murray, $38

There is a considerable amount about Lou Reed (and Velvet Underground) at Elsewhere, starting here.

post a comment