Graham Reid | | 9 min read

Good news arrives in small paragraphs. Take, for example, remarks from John Caldwell, a professor at the Australian National University in Canberra, at a United Nations conference on demography.

If his report was published at all, it

was buried behind the stories of tanks rolling into Palestinian camps

and the usual warnings about the decline of civilisation through

pollution, poor spelling and video games.

But Caldwell spoke of a

large ray of light. It appears fertility is dropping to lower than

expected levels and the trend means that over-population, long the

bogeyman to frighten an already nervous planet, might not

happen.

Caldwell even said the world's population - once expected

to exceed 10 billion, up from the present 6.1 billion - might pass

itself on the way down again.

This is a rare piece of good news -

but would have come as no surprise to Dr Bjorn Lomborg, once an

inconspicuous statistician and associate professor of political

science at the University of Aarhus in Denmark, who is now a

household name and bete noire in the homes of insecure

environmentalists everywhere.

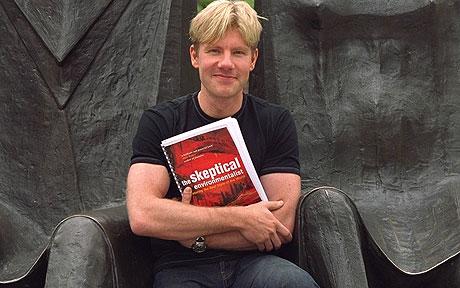

Lomborg, a 36-year-old Dane with the

boyish good looks of a Eurovision song contest competitor, announced

last year that things were not as bad as we had been led to believe,

and were actually considerably better.

A former member of

Greenpeace, Lomborg is a different kind of Euro-sceptic, and a highly

unpopular one with the many scientists and eco-activists who recoiled

from his projections of a moderately bright future on uncrowded,

increasingly clean and fossil fuel-dependent Planet Earth.

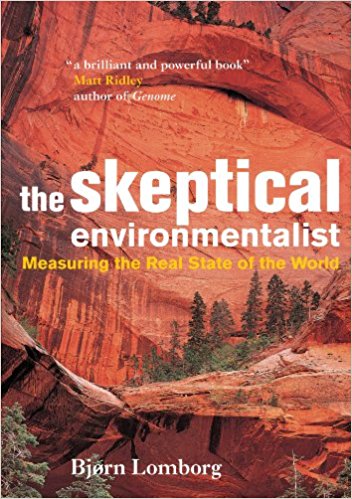

Lomborg's

controversial book, The Skeptical Environmentalist, published by

Cambridge University Press last year, made some radical and

unfashionable claims which grabbed headlines and column centimetres.

The Herald's lengthy article last June was one of hundreds that

appeared in the international press and which tossed this researcher

into a lions' den of claim and counter-claim.

Lomborg's

controversial book, The Skeptical Environmentalist, published by

Cambridge University Press last year, made some radical and

unfashionable claims which grabbed headlines and column centimetres.

The Herald's lengthy article last June was one of hundreds that

appeared in the international press and which tossed this researcher

into a lions' den of claim and counter-claim.

According to

Lomborg's findings, while the threat of biodiversity loss is real, it

is exaggerated. His statistical studies also showed our air and water

is becoming less polluted, that the population explosion predicted by

Dr Paul Ehrlich's 1968 book, The Population Bomb, which asserted

hundreds of millions starving to death in the 1970s, simply didn't

happen, that natural resources are not running out, and it is far too

expensive to do anything about global warming.

His book, 350 pages

of jargon-free language and with a whopping 2930 footnotes, tackled

doomsayers such as Isaac Asimov and Frederick Pohl, who wrote in 1991

that it was already too late to save the planet and all we could do

was decide just how bad we were willing to let things get.

"Mankind's

lot has actually improved in terms of practically every measurable

indicator," wrote Lomborg. But he cautioned that while things

have improved, that doesn't mean it's good enough.

Even so,

Lomborg was giving a big thumbs-up and his book, which effectively

skewered the environmental-protection industries for their alarmist

scenarios, came trailing favourable reviews from The Economist, the

New York Times, the Wall Street Journal and even Rolling Stone.

Because of its populist style it was one of the few science books

reviewed in the popular press.

Matt Ridley, author of Genome (an

analysis of the 23 human chromosomes), considered it something which

"should be read by every environmentalist so that the appalling

errors of fact the environmental movement has made in the past are

not repeated".

Needless to say, the environmental lobby and

many scientists saw it somewhat differently and the author has since

been at the centre of a firefight.

Lomborg, with appropriately

lefty interests such as the use of surveys in public administration,

was accused of misinterpreting or being selective with his data. He

was pilloried for not being an environmental scientist (his degree is

in political science), nailed as an anti-environmentalist who gave

comfort to the machinery of rapacious capitalism, and much

more.

Websites crackled with angry accusations, and the considered

response of fellow-author Mark Lynas, who is working on a book about

the effects of climate change, was to shove a pie in Lomborg's face

at a book-signing in London.

"I don't see why the environment

should suffer every time some bored, obscure academic fancies an ego

trip. This book is full of dangerous nonsense," he said after

delivering Lomborg what media reports waggishly called "his just

desserts".

The debate has been heated, but scientific

journals full of technical talk and graphs don't have the

headline-grabbing glamour of a good stoush. And for laypeople, the

science-speak which refutes Lomborg is too dense to be

comprehensible.

Among the other charges, many scientists say

Lomborg has exaggerated for effect (a device he criticises others for

doing) and that he used discontinued data. There were also

suggestions of an evil conspiracy.

Richard Bell, of the Worldwatch

Institute, noted that the Washington Post reviewer was Dennis Dutton,

identified as "a professor of philosophy who lectures on the

dangers of pseudoscience at the science faculties of the University

of Canterbury in New Zealand". Dutton - who hailed the book as

"the most significant work on the environment since the

appearance of its polar opposite, Rachel Carson's Silent Spring, in

1962" - is also the editor of the website Arts and Letters

Daily.

Bell said darkly, "The Post did not tell its readers

that Dutton's website features links to the Global Climate Coalition,

an anti-Kyoto consortium of oil and coal businesses".

To be

fair, the Post also didn't tell you Dutton's website has links to

ifeminist, the religious studies journal Killing the Buddha, Village

Voice and about 100 other magazines, journals and newspapers. It also

has "Lomborg pro and con" pages.

High-profile Canadian

environmentalist David Suzuki, who visited New Zealand this month,

was sceptical, not to say downright cynical, about why The Skeptical

Environmentalist had received such wide coverage.

It was not only

a good news story - rare in the media - but on his website he

suggested "the reason the book received so much publicity is

because of the deep pockets and influence of some big businesses that

have vested interests in maintaining the status quo".

He too

cited Lomborg's take on the state of the planet as similar to the

positions of some large industry-financed institutes and groups, such

as the Global Climate Coalition.

"These groups wage

big-budget campaigns to confuse the public about issues like air

pollution and global warming."

And yet, says Suzuki,

Lomborg's views went largely unchallenged in the media, although his

beliefs ran contrary to most scientific opinion and, even before his

book was published in North America, his views had already been

widely discredited by many of his colleagues at Aarhus

University.

Other Lomborg critics said that by coming under the

imprint of Cambridge University Press, one of the most hallowed of

names in scientific publishing, his book was afforded immediate

cachet and credibility by book review editors, and it was often

reviewed by those without the time and resources to analyse that

litany of footnotes. Who checks footnotes anyway?

Well, some

scientists did - and found Lomborg's research and interpretations

wanting. In January Scientific American ran an 11-page attack on

Lomborg which contained articles by four well-known environmental

specialists: Stephen Schneider of Stanford University; environmental

scientist and energy expert John P. Holdren of Harvard; John

Bongaarts, a vice president at the Population Council in New York

City, and Thomas Lovejoy, chief biodiversity adviser to the World

Bank.

They battered Lomborg for "egregious distortions"

(Schneider), for "elementary blunders of quantitative

manipulation and presentation that no self-respecting statistician

ought to commit" (Holdren), and for sections "poorly

researched and presented ... shallow ... rife with careless mistakes"

(Lovejoy).

The real concern is that while Lomborg grabbed the

headlines and book reviews, those who are challenging his contentions

are not getting equal time. The Union of Concerned Scientists'

webpage opened with the quote by Sir Winston Churchill: "A lie

gets halfway round the world before the truth has a chance to get its

pants on."

In fact some scientists looked at Lomborg's book early on, but simply dismissed it as foolishness. It was only after articles started appearing which said Lomborg had exposed environmentalists as wrong about just about everything that the scientific community realised it had a fight on its hands.

And it still rages.

One simple

question comes up frequently: Why has Lomborg had no support from any

major environmental organisation anywhere in the world for his

assertions?

The answer is perhaps obvious: it is hardly in any

such agencies' interests (especially if it is seeking government

funding or public donations) to lie down with those who might say

things are hunky-dory.

"I thought initially we would have a

couple of weeks of debate and that would be it and we'd all move on,"

said Lomborg recently. "But it just kept on and on and

on."

That's because saving the planet is a big business full

of professional lobbyists and fundraisers, market share jargon and ad

agencies. And for business to be good it must expand.

Patrick

Moore, one of the co-founders of Greenpeace who fell out with the

organisation over its radical tactics, has long asserted that, having

been successful in its early battles, the environmental lobbies had

to invent new concerns.

Despite the international outcry, the

Danish Government announced it was appointing Lomborg to head a new,

small environmental monitoring agency, the Institute for

Environmental Evaluation. Its mission will be to decide the best ways

to spend taxpayer dollars on environmental remediation.

Many

environmentalists are mad as hell.

However, Lomborg has sent a

blast through the environmental lobbies, found sympathy within some

for the need to be objective rather than emotive, and produced some

curiously telling responses.

Tom Burke, a member of the Executive

Committee of Green Alliance, an environmental adviser to BP and as

green as it gets, wrote a lengthy plain-English rebuttal of Lomborg's

contentions which was apposite, tart and convincing, but also of

great interest to those who shove dollars in a Greenpeace envelope

and feel good when they walk to work rather than taking the

gas-guzzler out of the driveway.

Burke says no environmental

organisation or leading environmentalist asserts we are having an

energy crisis (it was in the 1970s when many did, apparently), that

environmentalists do not believe natural resources are running out

(that dates from the Club of Rome in 72), and "that some

environmentalists exploit, sometimes aggressively, the gap between

perceptions and reality, playing on people's fears to generate

headlines and revenues". These are revealing admissions from a

greenie on the inside.

Burke says no environmental

organisation or leading environmentalist asserts we are having an

energy crisis (it was in the 1970s when many did, apparently), that

environmentalists do not believe natural resources are running out

(that dates from the Club of Rome in 72), and "that some

environmentalists exploit, sometimes aggressively, the gap between

perceptions and reality, playing on people's fears to generate

headlines and revenues". These are revealing admissions from a

greenie on the inside.

And Suzuki's latest book, co-written with

Holly Dressel, is Good News for a Change, which counters the

criticism that environmentalists are all a bunch of doomsayers.

"We've got to give people a sense of hope ... thousands of

things [are] going in the right direction".

But that doesn't

change his overall message about the seriousness of our global

problems.

So maybe we're not going to eco-Hell. Or maybe it will

be worse than we've been warned. Or maybe we simply don't know. But

we do need to question closely the banner-wavers of all

persuasions.

On the Scientific American website author Michael

Shermer, the founding publisher of Skeptic magazine, has a column

headed "Baloney Detection" in which he makes a valuable

point. After challenging common beliefs held by many of his students,

he is often asked by them why they should believe him.

"My answer: You shouldn't."

post a comment