Graham Reid | | 6 min read

There is an easy and perhaps even amusing heresy to commit in New Zealand art: simply say aloud at a swanky cocktail party you think Colin McCahon is over-rated.

When the sound of foreheads being slapped and sharp intakes of breath have faded you can drill down: his palette was limited (no cheery sky-blue available, Colin?); his representational figures are child-like in execution; the symbolism of light and dark pretty obvious; the great scrawls of religious text dogmatic . . .

By this time, you are standing alone in a crowded room nursing your drink and looking for the door.

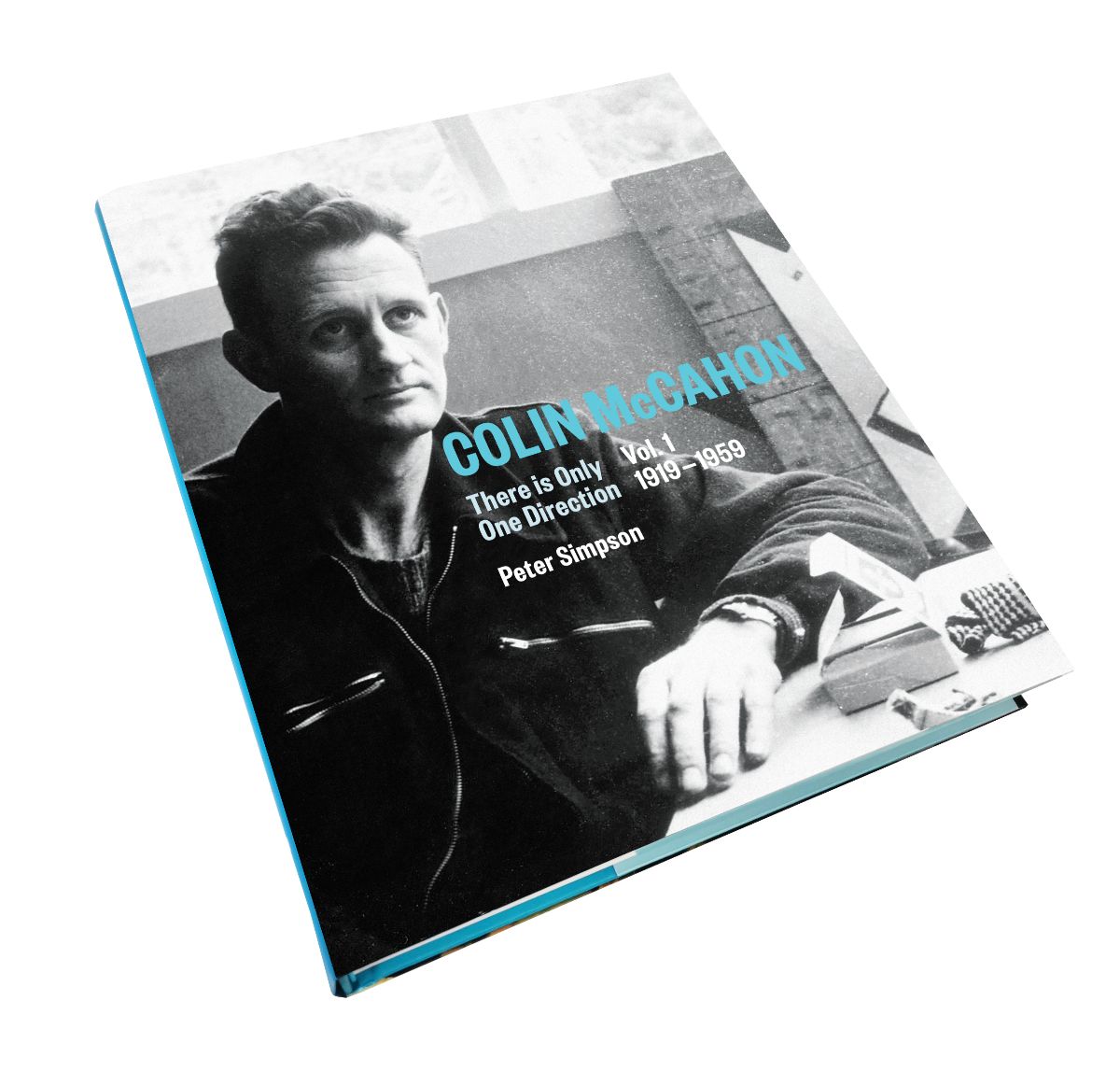

But if you've ever felt even just a smidgen of that (and perhaps more have than would dare admit), then this first volume of Peter Simpson's excellent and insightful biography of the artist and his work (more the work than the private life) is the necessary corrective.

In the plain, thoughtful prose and assiduous research which have been the hallmarks of his previous books – the arts in Christchurch for two decades after '33 (Bloomsbury South) and the art of Leo Bensemann -- Simpson again applies an academic rigour to his subject, but without resort to the grinding clichés of art jargon.

Nowhere here are spaces interrogated, the artist in a dialogue with the landscape (to quote Tom Wolfe in From Bauhaus to Our House, “What did the landscape say?”) or minor works elevated by means of a curator's polysyllables and impenetrable prose.

This former Associate Professor of English at the University of Auckland – who has prior form writing about McCahon and curating exhibitions of the artist's work – is again a generous guide who chronicles the first four decades of the life of the artist, the centenary of whose birth is being celebrated this year.

With access to letters, the acknowledgement that McCahon was occasionally an unreliable witness or self-mythologising about his own career, and that some of his work failed to find favour with even his supporters, Simpson offers a clear-eyed and perceptive account. And it is housed in a handsome, large-format hardback filled with colour and black'n'white reproductions of hundreds of McCahon's paintings and drawings alongside personal photos of McCahon with family and friends, catalogue covers, sketches and much more.

The result is a rounded picture of an artist whose early life was suffused in religion (Presbyterian, Quaker), who had a powerful love of - and response to - the landscapes of the South Island, and an overwhelming belief in art which allowed his exploration of the world and emotional responses to it.

Although as Simpson notes, while his work was not always met with acclaim “it would be wrong, however, as sometimes happens, to depict McCahon as a prophet not recognised in his own country. He was certainly not universally admired in his lifetime, or, indeed, since it ended. There were always nay-sayers, and still are”.

The loner at the cocktail party could count ARD Fairburn among his company, the writer dismissed McCahon's text-inclusive work in '47 saying in Landfall, “they might pass as graffiti on the walls of some celestial lavatory ...”

And Charles Brash in particular always seemed to prefer McCahon's earlier work than whatever the artist was producing at the time.

McCahon seems to have largely ignored or simply been immune to such commentary. He was on a singular journey: “I was very lucky and grew up knowing I would be a painter,” he wrote in '72.

Landscapes drew him early.

As Simpson observes, most of McCahon's work during his art school years in Dunedin ('37 – '39) were landscapes . . . and he spent a great deal of time out in the world during the summer months when looking for paid employment, a notable period in Nelson where he spent time in Toss Woollaston's clay-brick house at nearby Mapua.

Woollaston's own paintings of Mapua are rich in colour but McCahon's landscapes into the Forties (of Nelson and the Otago Peninsula) emphasise dark greens and browns, unpopulated space of valleys and triangular hills worn smooth.

By the end of the decade there are remarkably powerful works such as Takaka: Night and Day, Triple Takaka, The Sink-Hole Landscape and the astonishing and minimal The Green Plain.

By the end of the decade there are remarkably powerful works such as Takaka: Night and Day, Triple Takaka, The Sink-Hole Landscape and the astonishing and minimal The Green Plain.

His flat Canterbury Plains is influenced by the linear aspects of Cubism and remains extraordinary.

And despite being very much a New Zealand painter (in the definition of him as “painting New Zealand”), McCahon didn't embrace the emerging impetus towards nationalism in the arts as enthusiastically – or dogmatically – as many of his peers.

He was on that singular journey.

Parallel to these landscapes and other works in this period were his religious paintings where the symbols of the lamp and the jug made their appearance, and of course text being a significant painterly element. Simpson notes McCahon's speech bubbles and scrolls in the work owing a debt to advertisements (a Rinso packet) and perhaps Classic Comics.

McCahon was nothing if not visually curious, which explains why he was such a restless spirit. He was assimilating, adopting and adapting rapidly from high art – “the real tradition comes from Giotto, Michelangelo, Gaugin” he wrote in '45 – and low culture, and while remaining true to his imagery and vision, pushing into new territory.

In his early days he was remarkably self-assured: “So having certain knowledge that I am one of the very few who can paint well in this country I shall paint & conserve energy for that end by living with that end in view,” he wrote to his sister Beatrice in the same year.

He was in his mid-twenties.

Simpson singles out key moments such as McCahon seeing linemen on a scaffold at Mapua in which he deduced an image of the crucifixion, which he would explore.

Magnificent landscapes would follow in the Fifties: the angularity of the Otago and Canterbury landscapes, the unusually colourful and sinuous lines of A Southern Landscape … and the powerful triptych of On Building Bridges where robust manmade structures in the foreground allude to religious symbols (the Tau cross) against the backdrop of Cubist landscapes and mysteriously dark areas.

Simpson follows McCahon to Auckland – specifically Titirangi for his five years in the city after 1953 – and although the artist missed friends, he was glad to leave the South Island and enjoyed the warmer climate, the greater Polynesian presence, the dense bush and the nearby beach: “The bush is magnificent. Kauris in spring are real Xmas trees – the new leaves glitter.”

He didn't start painting immediately in Titirangi (there was a garden to create) and in Simpson's overview the author notes that this layoff was a pattern McCahon would repeat when changing location.

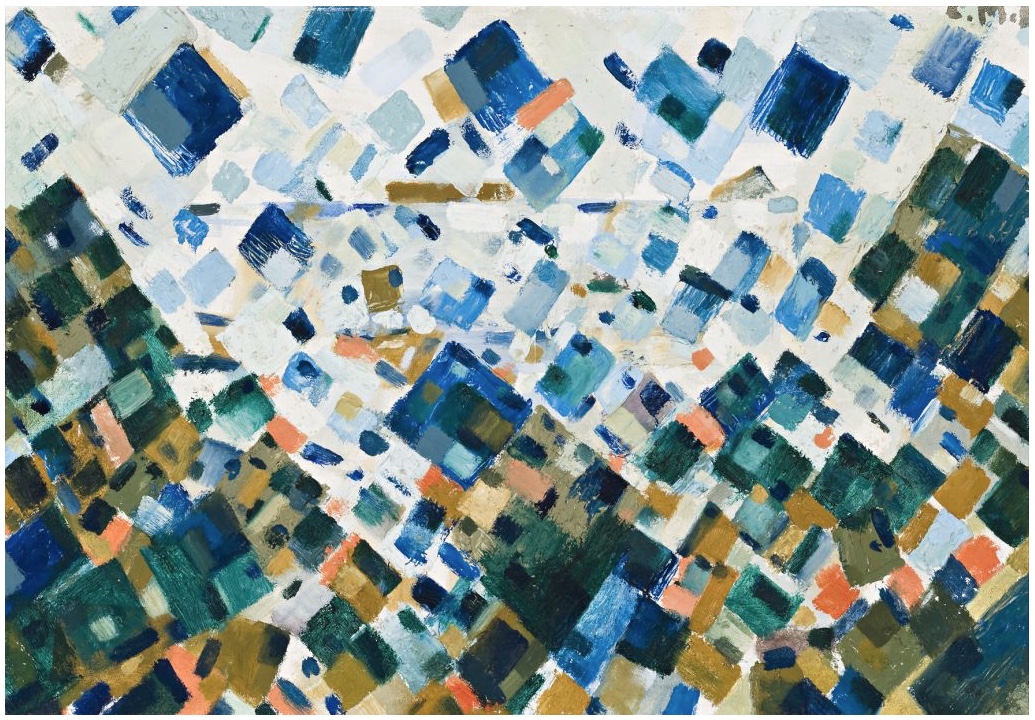

Titirangi and the light prompted new directions, into abstraction and vivid colour (the wonderfully radiant paintings and abstracts of French Bay) which give the lie to that jocular heresy of his palette being limited.

Titirangi and the light prompted new directions, into abstraction and vivid colour (the wonderfully radiant paintings and abstracts of French Bay) which give the lie to that jocular heresy of his palette being limited.

Simpson charts a course through McCahon's work in this enormously productive and artistically diverse period in Titirangi – which also produced the seminal I AM in '54, small in scale but as Simpson says “the words are monumental in effect”.

Simpson writes in a seemingly effortless manner where the work, the man, the mythology and the magisterial work of the Northland panels and Elias paintings are the natural outgrowth of McCahon's investigations and intellect.

Unlike a curator who writes to "sell" an artist or a work, throughout these 370 pages Peter Simpson astutely points to the art and makes subtle connections of imagery, intent and source material in the broader context of the artist's life and other works. That is a more persuasive and intelligent style of writing about art because, in this instance and in his previous books, he allows the reader to also follow the threads and make discoveries.

This first volume closes on McCahon's 40thbirthday at the end of 1959, a moment which – as the author notes – marks the halfway point of his artistic career where the landscapes have gained power, depth and sometimes darkness, and words have now replaced figures in his deeply resonant Biblical paintings.

More, much more, would follow, of course.

This is an excellent, scrupulously annotated and engagingly written book … and the perfect gift for that loner at the cocktail party nursing a drink after, even if only in jest, having said Colin McCahon was overrated.

COLIN McCAHON: THERE IS ONLY ONE DIRECTION. VOL. I 1919 - 1959 by PETER SIMPSON (Auckland University Press, $75)

COLIN McCAHON: IS THIS THE PROMISED LAND? VOL II 1960 – 1987 will be published by AUP in May 2020.

post a comment