Graham Reid | | 3 min read

Over the years when it was clear I was not cut out to be a marine biologist – the university, unfairly I believe, thought I should pass my papers in order to advance my career – I remained curious about Darwin's voyage, his scientific explorations and his thinking.

In the past decade or so I bought the six CD box set of the Darwin Lectures recorded in Auckland in 2008 by RadioNZ, reveled in a BBC radio series which asked odd but obvious questions such as “what was Darwin doing on the Beagle anyway?” and so on.

Of course a visit to the jungles of South America and the remote Galapagos islands where he really started to formulate his theory of natural selection were always beckoning.

My travels only once took me to South America and then, maybe about 15 years ago, I saw a television programme about the remote Galapagos . . . which proved not to be so remote that they weren't being overrun by tourists coming from Ecuador.

Like a trip to Antarctica, the Galapagos went straight off my to-see list.

Those places didn't need my presence or unwelcome intrusions on their landscape.

In area, the Galapagos islands are huge, of course.

There are 18 of them and most places have never known a human footprint.

Just how huge comes back in this book of photographs and short text by Tui De Roy who arrived there with her parents in December 1955 when she was two.

Her parents Andre and Jacqueline from Brussels had wanted to escape city life and after time in Corsica learned about the Galapagos and so – years before it was declared a national park and became a tourist destination – they arrived there, build a home out of lava rock and brought up their family of Tui and her younger brother.

Her parents had brought cameras and, surrounded by such a rich environment of animals and landscapes, for half a century Tui – who these days divides her time between there and New Zealand – became a nature photographer as well as guide on expeditions by scientists.

Her colour photos in this A4-sized, 240 page collection attest to the strange beauty of the islands, the diverse fauna and flora which has – until now anyway – flourished and diversified over many, many centuries, and the seeming indifference of ancient-looking animals to human presence.

Her colour photos in this A4-sized, 240 page collection attest to the strange beauty of the islands, the diverse fauna and flora which has – until now anyway – flourished and diversified over many, many centuries, and the seeming indifference of ancient-looking animals to human presence.

In chapters such as Their World, Their Ways we see snapshots from the lives of birds engaging with each other and other species, and how sea lions play with each other and toys (crabs, starfish).

The reader feels like the silent observer of these frozen moments which have been played out over millennia.

No more so is that apparent in the images of impassive marine iguanas beneath a sky ablaze with a billion stars, or them like surfers negotiating the huge, clear waters off the shore of vast Fernandina.

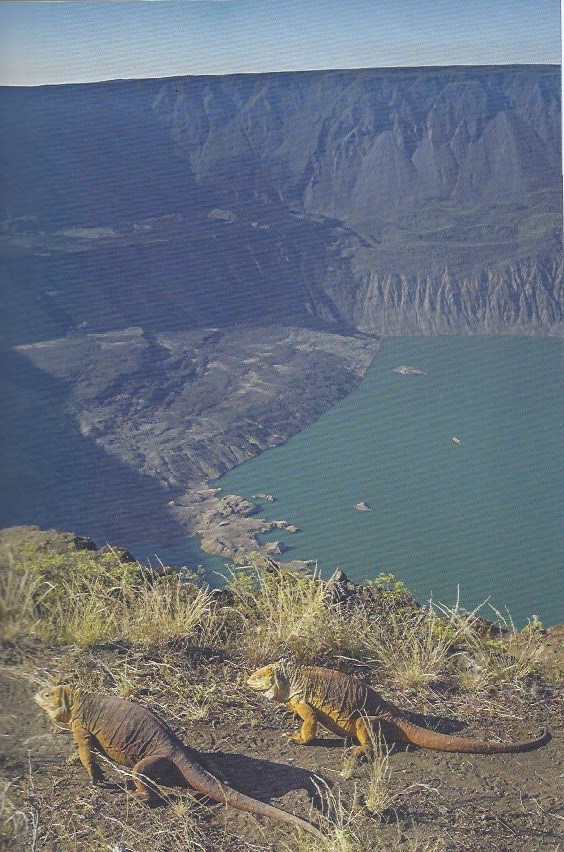

But for me the magic of these pages is in the vast landscapes away from the foreshores where the animals (and doubtless the tourists not pictured here) gather.

Inland on the larger islands are great vista more like the dry deserts of Arizona, craters and lakes of enormous size, places of lunar emptiness where few animals tread and are almost devoid of plantlife . . .

There are plains of grass rolling to the horizon, turtles bathing in rain puddles on what might be a sweep of the Serengeti, wind-bitten cacti poking from lava flows, thick forests with moss hanging from branches . . .

Little wonder that life here diversifies to take advantage of these very different environments.

And there is the life beneath the ocean's surface which 66-year old De Roy – stranded on Galapagos during Covid-19 when she returned there laste last year to write her autobiography – has photographed also.

And – aside from a couple of photos of her parents and family, and some of people involved in conservation – there is not a human in sight in these pages.

That's the way I want my Galapagos to be.

I'm happy not to go there and trouble it, and to turn these pages instead.

And wonder.

A LIFETIME IN GALAPAGOS by TUI DE ROY Bateman Books $60

post a comment