Graham Reid | | 4 min read

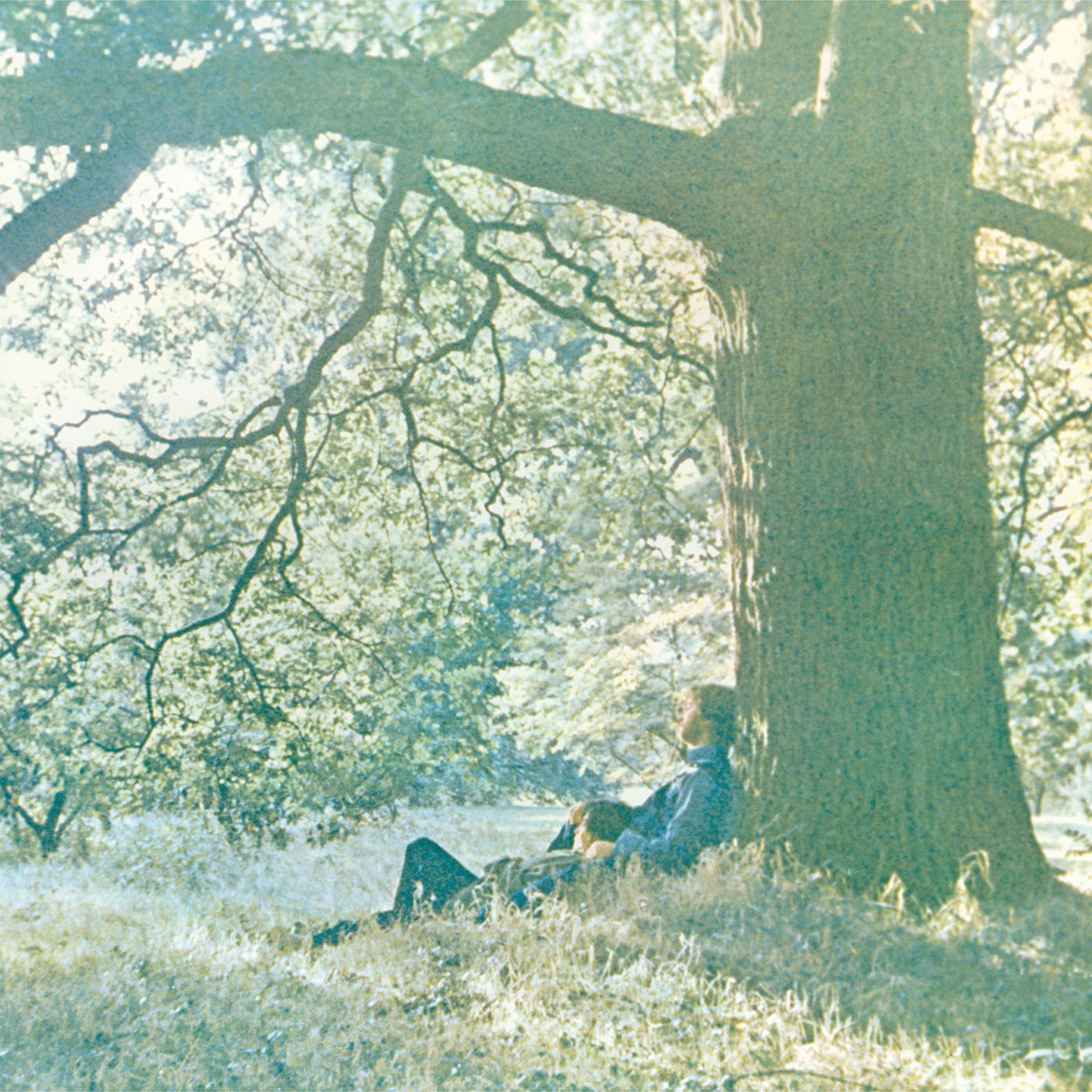

In 1970, John Lennon and Yoko Ono simultaneously released albums which were defining in their careers and, in deliberately similar covers, both appeared as Plastic Ono Band albums.

Lennon's Imagine of the following year may have sold a lot more – spurred on by the single – but no other album in his life was as coherent and as courageous as John Lennon/Plastic Ono Band.

The Yoko Ono/Plastic Ono Band album however – certainly as courageous and confrontational in its own way – unfortunately defined Ono in the public shorthand as a tuneless screamer of little talent who had only got their on the coattails of her husband.

The Yoko Ono/Plastic Ono Band album however – certainly as courageous and confrontational in its own way – unfortunately defined Ono in the public shorthand as a tuneless screamer of little talent who had only got their on the coattails of her husband.

That is far from the truth and it has long been an Essential Elsewhere Album.

But -- coupled with their peace and publicity antics, their drug bust and the widely believed story that she spilt up the Beatles – meant her POB album was relegated.

Lennon's POB album however, even now, sounds as emotionally raw as it did at the time when, after screaming sessions as part of Primal Therapy, he got in touch with his deep pain (abandoned by his father, reconnecting with his mother only to lose here when she was killed by car) and uncertainties.

His song Mother addressed the former (“you had me but I never had you”) and Isolation spoke to the latter.

Most attention alighted on God in which, after a litany of rejected heroes and beliefs, (Jesus, mantra, Kennedy and more) he announced, “I don't believe in Beatles, I just believe in me, Yoko and me”.

No other artist had so resoundingly rejected his image (“I was the dreamweaver but now I'm reborn, I was the walrus, but now I am John”) and let the myths and his audience be pushed away: “And so dear friends you'll just have to carry on [without Beatle John]”.

These two POB records were albums-as-therapy and the wounds revealed were so open and sore – Ono's screamed out often wordlessly, Lennon's sometimes screamed as on Mother and Well Well Well but just often more reflective – that they stand scrutiny today.

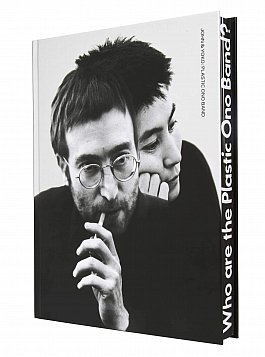

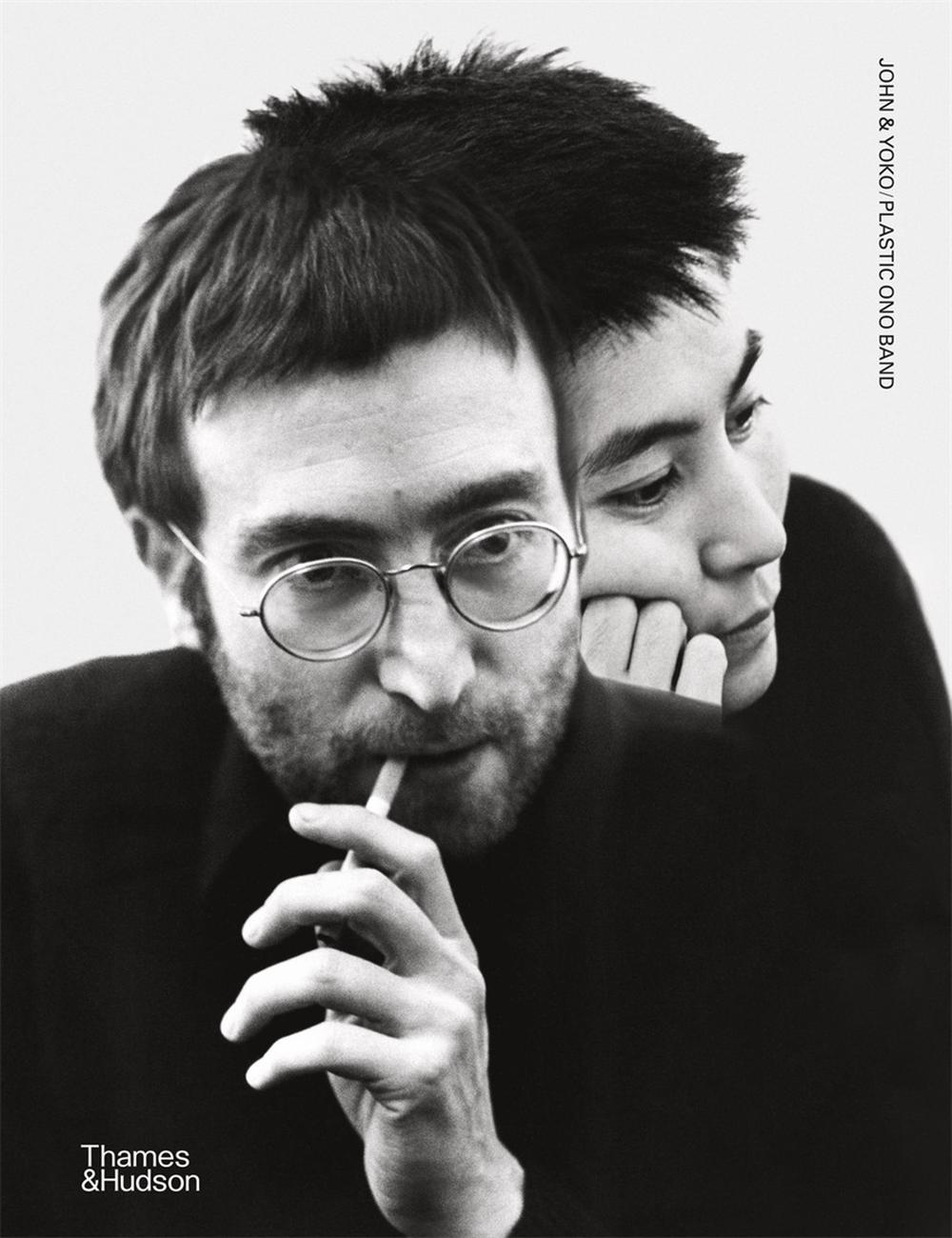

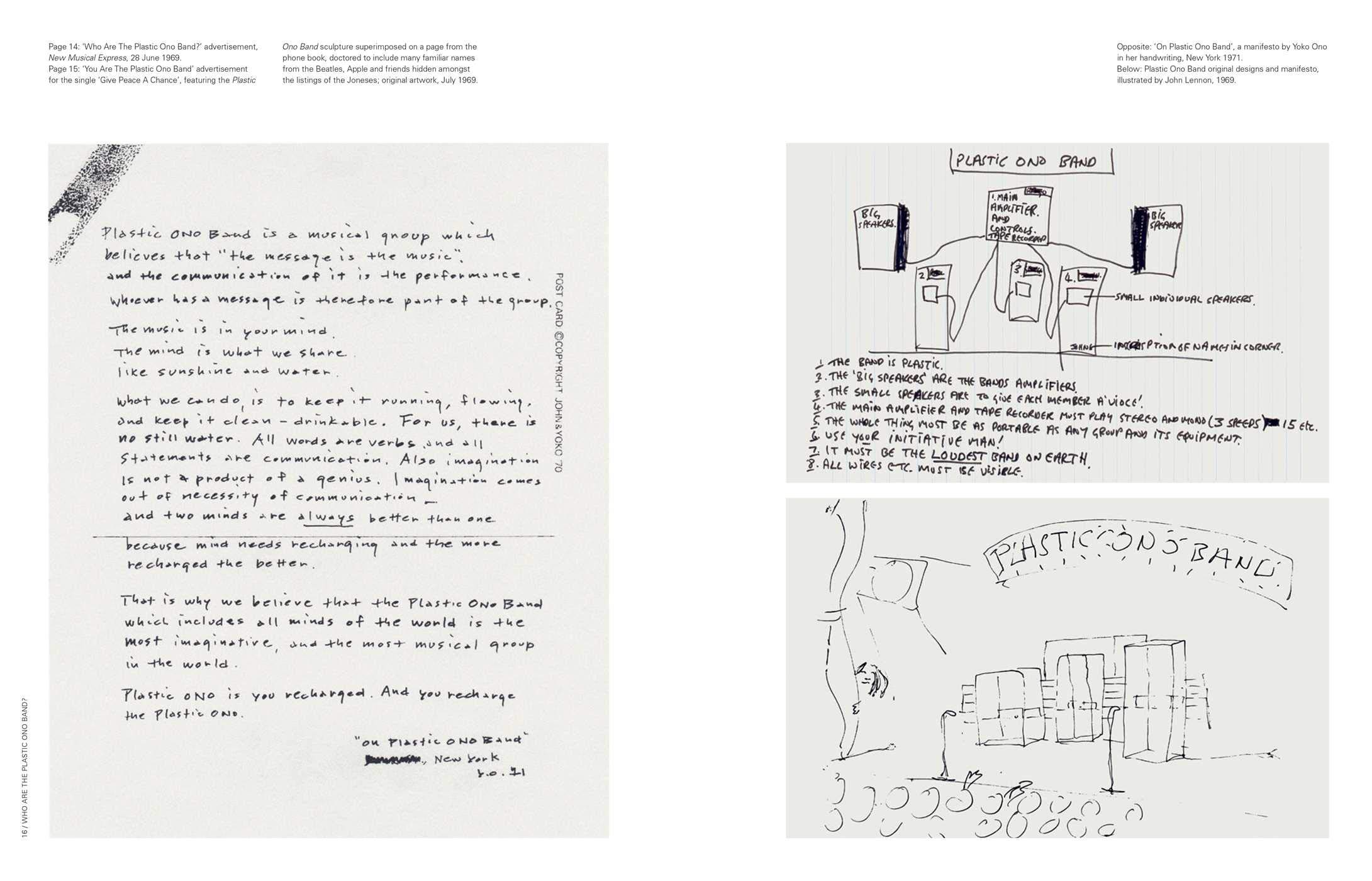

The Plastic Ono Band was an interesting concept in itself and this handsome, profusely illustrated hardback with scores of previously unpublished photographs and incisive text of pertinent quotes from Lennon, Ono, Timothy and Rosemary Leary, George Harrison and Ringo Starr, fellow travelers, band members and others. Taken together with the lyrics and art, the large-format book sheds light on just how and why the POB concept emerged and took life.

The idea had its genesis in '69 when Lennon and Ono held their Bed-In at a hotel in Montreal and recorded Give Peace a Chance with a motley assembly of guests which included the Learys, Tommy Smothers and, improbably, Petula Clark who tells a lovely story about why and how she came to be there.

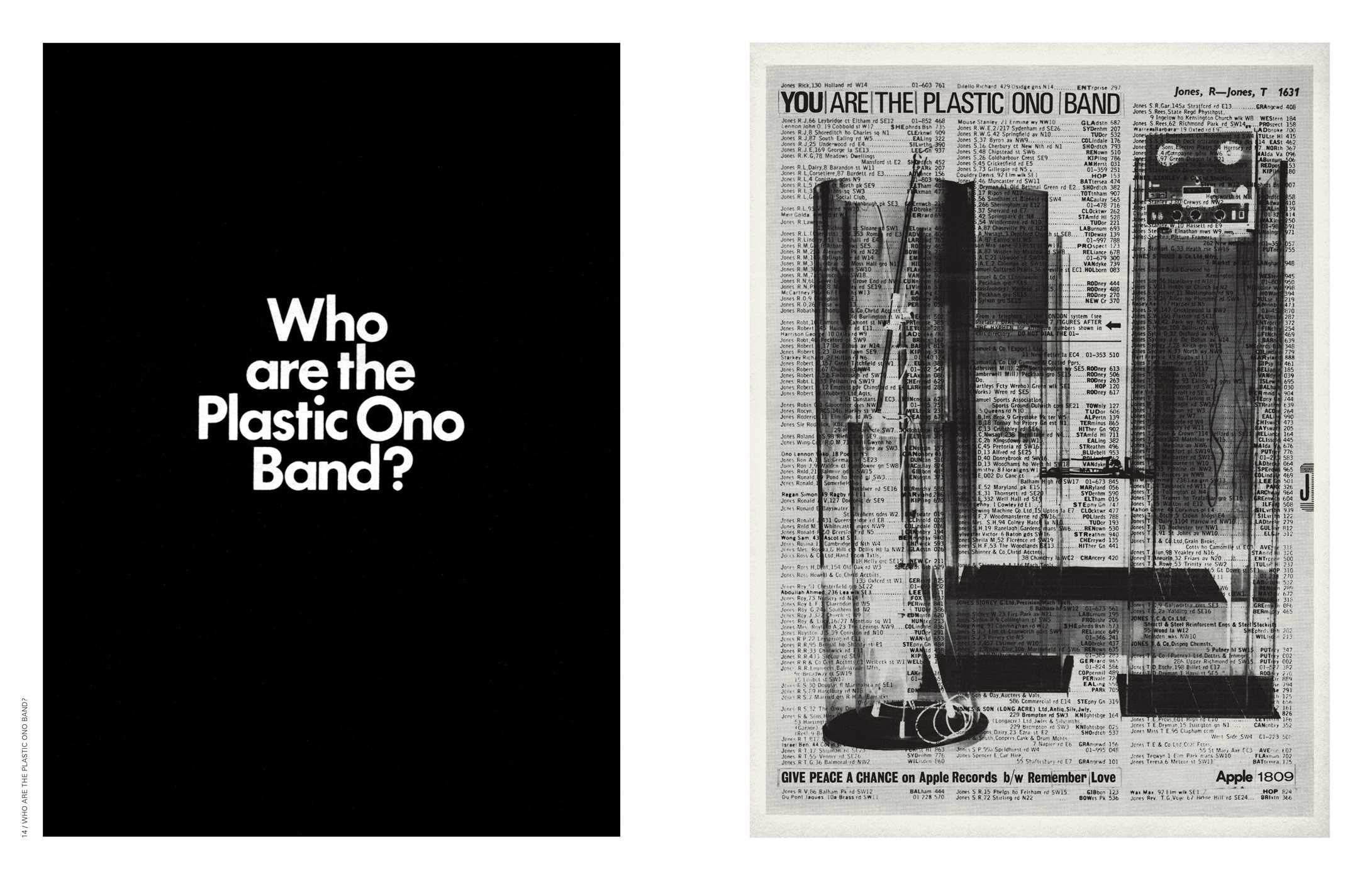

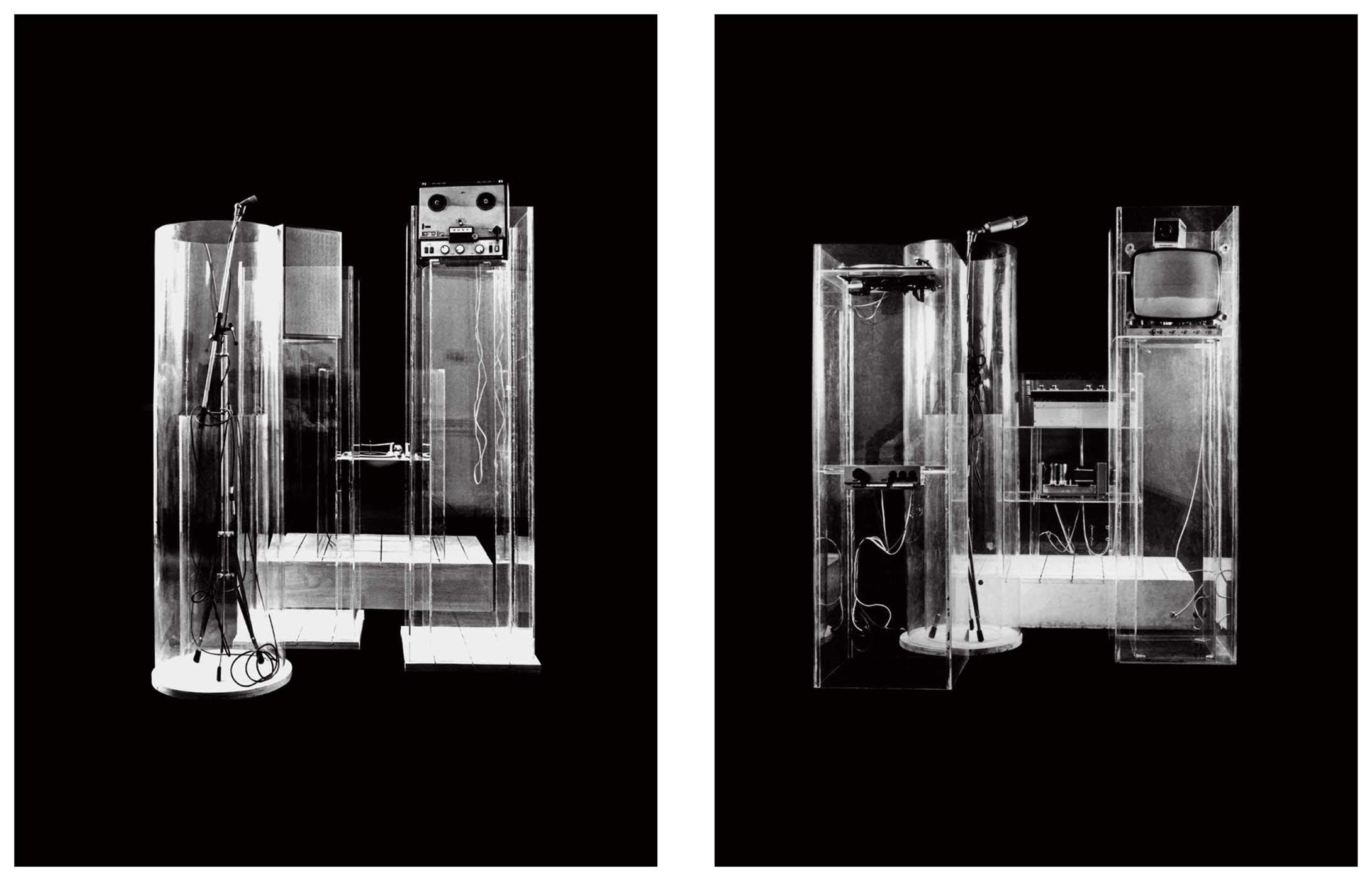

When the song was released under the name Plastic Ono Band – in a cover which was of a perspex collage of a conceptual “band” by Lennon – the promotion was inclusive: “YOU are the the Plastic Ono Band”.

The as-yet undefined idea being that the “band” would have a revolving door of members . . . or something like that.

In fact the band firmed up when Lennon and Ono were invited to MC a rock'n'roll festival in Toronto where many of his heroes (Bo Diddley, Jerry Lee Lewis, Chuck Berry) were to appear.

Ticket sales were low and slow, so Kim Fowley called Lennon to see if they would come over.

Lennon – who hadn't played live in some time – decided to quickly pull together a band (Eric Clapton, bassist Klaus Voorman and 20-year old drummer Alan White) and they rehearsed on the flight over.

Lennon – who hadn't played live in some time – decided to quickly pull together a band (Eric Clapton, bassist Klaus Voorman and 20-year old drummer Alan White) and they rehearsed on the flight over.

At the concert where their set was recorded and rush released as Live Peace in Toronto 1969 Lennon announced at the start, “W're just goin' to play numbers that we know, you know. Because we've never played together before”.

And they did exactly that as chronological tour through rock'n'roll from the formative past (Blue Suede Shoes, Money, Dizzy Miss Lizzie) to the recent present (Yer Blues from The White Album), his new songs Cold Turkey and Give Peace a Chance, then into some imagined future with Yoko Ono and the band jamming for almost 20 minutes.

It was and remains an extraordinary album in its spontaneity, humour and seriousness when Ono starts in and the band just has to riff along and see where the thing goes.

And so the POB had a stake in the ground: after that there was the raw and reductive pop of Instant Karma and then those paired Plastic Ono Band albums (with Voorman and Ringo and, as with the Karma single, Phil Spector co-producing).

Who Are the Plastic Ono Band? tells of all of this in detail and the story goes backwards and forwards around this period.

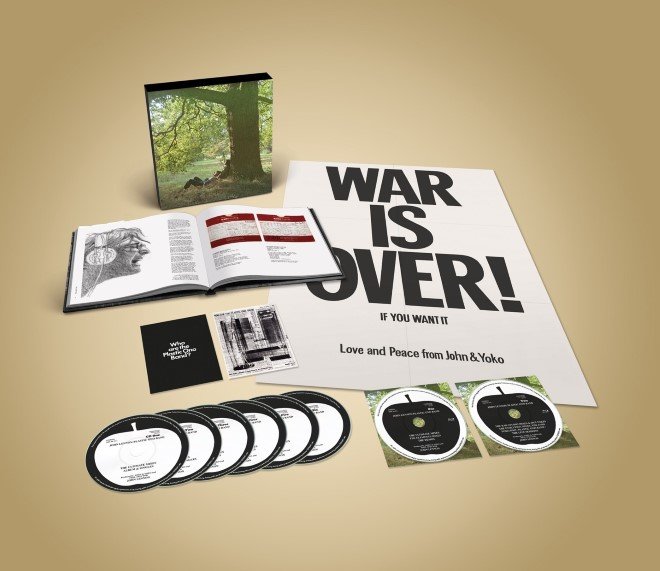

With the impending release of the six CD box set of Plastic Ono Band sessions this book is more than just a useful background reader but an insight into the thinking which, to outsiders, could seem haphazard and made up on the fly.

With the impending release of the six CD box set of Plastic Ono Band sessions this book is more than just a useful background reader but an insight into the thinking which, to outsiders, could seem haphazard and made up on the fly.

But there was a conceptual, guiding ethos which meant the POB idea could spring to life for quick singles or concerts.

You'd love to hear a recording of the show at London's Lyceum Ballroom where there were 17 musicians on stage including Keith Moon, Harrison, Clapton, horn players and Delaney and Bonnie . . .

It would have been rambunctious, undisciplined but a whole lot of fun for musicians who just got together to play because they wanted to.

The conceptual ethos of the Plastic Ono Band allowed for that.

.

Elsewhere has a number of articles about, and interviews with, Yoko Ono about her own work and that of John Lennon (his music and art included) See here.

.

.

.

post a comment